Small modular reactor project likely to end badly for utilities and worse for taxpayers

Key Findings

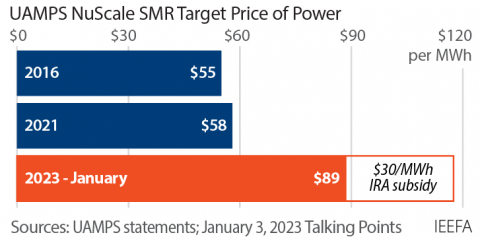

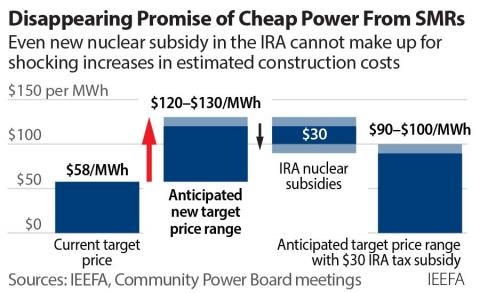

The estimated cost of the power from a 462-megawatt small modular reactor designed by NuScale and supported by more than two dozen Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems (UAMPS) members has risen dramatically, from $58 per megawatt-hour to $89 per megawatt-hour

Despite assurances that costs of future reactors won’t be as high because of a learning curve associated with repetition, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology study has found that the costs of building successive nuclear plants cost more than the original project

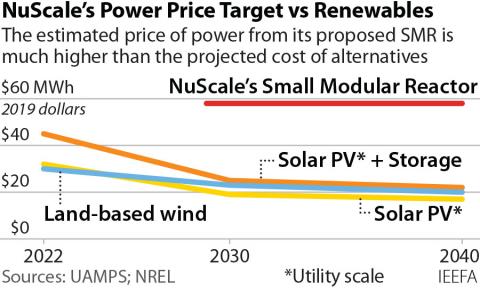

Cleaner, cheaper alternatives to the NuScale small modular reactor project are abundant in the western U.S.—including the seven states in the UAMPS service area—and include such proven technologies as solar, wind, and geothermal energy

Solar and wind power, augmented by battery storage, are becoming less expensive. Hydropower and geothermal energy already are providing substantial amounts of power in many parts of the country. Cost-effective, proven technologies exist and can speed the transition to a carbon-free economy.

Small modular reactors (SMRs) designed by NuScale are not among them.

More than two dozen of the 48 Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems (UAMPS) members have signed on to buy power from the NuScale SMR when the project is planned to come online in 2029. But a history of the project—and of nuclear energy projects in general—suggests the project is likely to end badly for utilities and worse for ratepayers.

UAMPS announced earlier this month that the cost per megawatt-hour (MWh), a unit of measurement roughly equivalent to the electricity used by the average U.S. home for a little more than a month, has risen from $58/MWh to $89/MWh, a 53 percent increase. Plus, the cost of power from the project would be much higher than $89/MWh without more than $4 billion in subsidies the project would receive from the U.S. government. Already, the total cost of the project has risen from $5.3 billion to $9.3 billion.

Nuclear advocates often claim that the costs of nuclear reactors fall after a first design, which (if true) would be very good news for the NuScale design. Unfortunately, the nuclear industry has never shown the ability to take advantage of a learning curve, and there is no evidence to suggest that it will be able to do so now. A 2020 Massachusetts Institute of Technology study found the costs of successive nuclear projects are more expensive than the original project, which is very bad news for the NuScale design.

It’s also not good news for ratepayers. New reactor designs are already notoriously expensive and highly unlikely to meet initial deadlines. The Westinghouse AP1000 design at Plant Vogtle in Georgia, for example, was originally expected to cost $14 billion and begin operation in 2016; its price tag has soared past $34 billion, and it won’t provide power until later this year. Think corporations like Georgia Power that are posting record profits will pick up the tab? Think again: Residential consumers have already eaten $1.66 billion of construction costs, with more on the menu.

To be sure, nuclear energy has some advantages. It doesn’t emit carbon dioxide, takes up a relatively small amount of space, and produces large amounts of energy. Its advantages, however, become far less apparent when the costs of a nuclear facility—and the time that it takes to build even a modest-sized project—are considered.

Proven, less-costly clean alternatives exist, especially in the western U.S. Geothermal, for example, made up 5.7 percent of California’s electricity generation in 2021; it was responsible for 9 percent in Nevada, and it’s being pushed as a much less expensive alternative to the NuScale project. Solar covers about 16 percent of Arizona electricity production and 6 percent in New Mexico. Almost 20 percent of Wyoming electricity comes from wind; in Idaho, the figure is about 16 percent.

The NuScale SMR is just another in a long line of overhyped and overpriced nuclear projects that take too much time and money—resources the planet doesn’t have in abundance if we’re serious about avoiding cataclysmic climate change by limiting global warming to 1.5⁰C by 2050.

Small modular reactors may be viable one day—but they are not today, will not be tomorrow, and may never make as much economic sense as renewable sources of electricity. We should stick to carbon-free energy sources that make financial and environmental sense.

This op-ed appeared in the Salt Lake City Tribune on January 19, 2023: David Schlissel: Small modular reactor project likely to end badly for Utah utilities

David Schlissel ([email protected]) is IEEFA director of resource planning analysis