Rio Grande LNG project could raise U.S. gas prices—and add to a looming global glut

Key Findings

NextDecade expects to make a final investment decision on its Rio Grande LNG export project within weeks, moving the U.S. gas market closer to shortages, volatility and higher prices.

The increase in LNG projects means the U.S. again is likely to export more natural gas – and import higher prices as companies seek greater profits from overseas markets.

Even absent the urgency for an energy transition to cleaner fuels, the world does not need more natural gas projects. Qatar, Canada, Russia, and Australia all have LNG projects under construction. A glut appears likely.

NextDecade, an upstart liquefied natural gas (LNG) developer that has been trying to move its Rio Grande LNG project forward for almost eight years, just moved one step closer to its goal. The company announced Wednesday that Global Infrastructure Partners, a New York-based private equity firm, had agreed to take a majority ownership stake in the project. NextDecade said that the French oil and gas giant TotalEnergies plans to take a minority stake in the project, and to buy 5.4 million tons of LNG annually from the facility for 20 years after it enters service.

With this announcement, NextDecade says that it’s on track to make a final investment decision to move forward on the project within weeks. Although NextDecade executives are likely breathing a sigh of relief, U.S. natural gas consumers should be wary.

With every new LNG export project that’s completed, U.S. gas markets move one step closer to shortages, volatility, and higher prices.

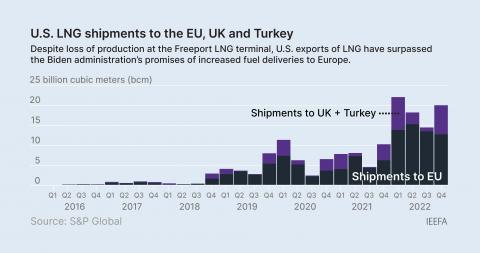

We saw the impact of LNG exports on U.S. gas prices all too clearly last year. As the Ukraine conflict raged and Russia slashed its gas exports, Europe backstopped missing Russian gas by buying every cargo of liquefied gas that it could, setting off a global LNG bidding war. LNG companies in the United States shipped more and more gas to take advantage of high global prices. America’s gas export surge forced U.S. consumers to compete with overseas buyers, pushing U.S. natural gas prices to their highest levels in well over a decade.

If there was any question about whether gas exports were to blame for rising gas prices in the U.S., the June 8, 2022, explosion of an LNG plant in Freeport, Texas, removed all doubt. The morning after the explosion, U.S. natural gas prices plummeted as gas traders realized that the closure of the terminal would ease demand for U.S. gas. Freeport LNG quickly announced that extensive repairs would keep the terminal offline for months, and gas prices fell once again. Even with Freeport out of the picture, the LNG plants that remained online exported enough gas to keep prices high for months, creating outsized pain for U.S. consumers.

As new export facilities come online, a repeat of 2022’s price spike will grow more likely. If NextDecade is able to secure financing for Rio Grande LNG, it will be the seventh LNG project under construction that relies on U.S. natural gas. Two facilities are currently being built in Mexico, both sourced with U.S. gas. Three brand new U.S. terminals are under construction: Golden Pass LNG, spearheaded by ExxonMobil and Qatar Petroleum; Sempra Energy’s terminal in Port Arthur, Texas; and Venture Global’s Plaquemines LNG project in Louisiana. There’s an expansion underway at Cheniere’s Corpus Christie LNG plant, as well.

If all seven projects are put into service, U.S. LNG export capacity—already high enough to create pain for consumers—will grow by 80 percent. The U.S. could be exporting as much as 22 billion cubic feet of gas per day, or more than one-fifth of all gas currently produced in the U.S. Additional LNG projects also are waiting in the wings, crossing their fingers that they’ll get a financial green light.

With all that gas export capacity, any hiccup in global gas markets could be enough to send U.S. prices gyrating.

The U.S. will be exporting more and more LNG, and importing more volatility and higher prices as a result.

A recent report from the U.S. Energy Information Administration adds analytic heft to concerns. The agency modeled long-term gas market dynamics, and concluded LNG exports would allow high global gas prices to filter into the U.S.—and that a fast LNG buildout would likely mean higher natural gas prices for U.S. homeowners and businesses.

One of the many ironies of the ongoing LNG buildout is that the global market may not actually need Rio Grande’s capacity at all. The U.S. is not the only country that’s building LNG export plants. Qatar, which produces the world’s cheapest LNG, is in the middle of a massive expansion. Meanwhile, Canada, Russia, and Australia all have LNG projects under construction, as do Mozambique, Indonesia, Senegal, Nigeria, and Gabon.

Although relatively little new export capacity is slated to come online over the next year, the tidal wave of new global LNG capacity is set to crest in 2026 and remain strong through 2027. There’s strong reason to believe that the global LNG market simply can’t absorb that much new supply so quickly. So if NextDecade moves forward with Rio Grande LNG, the project will likely open its doors in the middle of a multi-year global LNG glut.

Figure 1. Global LNG capacity additions (million metric tons per year)

Source: IEEFA, based on International Gas Union, S&P Global Commodity Insights, news reports and company announcements. Note, these figures represent projects currently under construction.

It’s important to note that last year’s sky-high gas prices dampened global demand growth. Europe’s gas consumption has fallen dramatically this year, with the Russia-Ukraine crisis accelerating the continent’s shift away from gas and towards renewables. Japan’s LNG consumption has fallen as well, and even Chinese gas consumption—once projected to be a major driver of global demand growth—has stalled.

The collision between robust supply growth and weak demand could be a financial catastrophe for TotalEnergies, which could wind up paying for millions of tons of LNG that the global market doesn’t need.

The project will undoubtedly be a reputational catastrophe as well. The Rio Grande LNG project has been roundly criticized by many residents of the Rio Grande valley, particularly historically marginalized Latino and indigenous communities working to protect one of the last relatively unspoiled regions of the Texas coast.

To make things worse, doubling down on Rio Grande LNG puts TotalEnergies’ long-term climate commitments at risk. While the LNG industry has engaged in a longstanding public relations campaign trying to portray LNG as a “clean” fuel, it’s anything but. What’s more, Rio Grande LNG’s gas feedstock would come from the Permian Basin, which is widely recognized as a hotspot for massive, pervasive, climate-warming methane leaks.

It's easy to see why the developers of Rio Grande LNG want the project to move forward. Simply securing the financing to build the project will make NextDecade’s executives and insiders wealthy. But it’s harder to understand why TotalEnergies would commit to buying so much LNG from the project. For a company that’s allegedly committed to be “Net Zero by 2050” to lock itself into buying some of the world’s most problematic LNG supplies through 2047 or 2048, starting off in the middle of an unprecedented market glut—that’s a decision that could be awfully difficult to explain to shareholders.