The liquefied natural gas (LNG) boom in Europe isn’t all good news for U.S. exporters

Key Findings

U.S. imports to Europe topped White House targets by mid-August

LNG shipments to Europe could hit 75 billion cubic meters by year’s end, up 44 bcm from 2021

Europe remains short of gas and is reducing gas demand and boosting renewables to fill gaps

The odd continent out is Asia, where high prices have made LNG unaffordable

Bottom line: U.S. LNG exporters shouldn’t count on the good times to continue

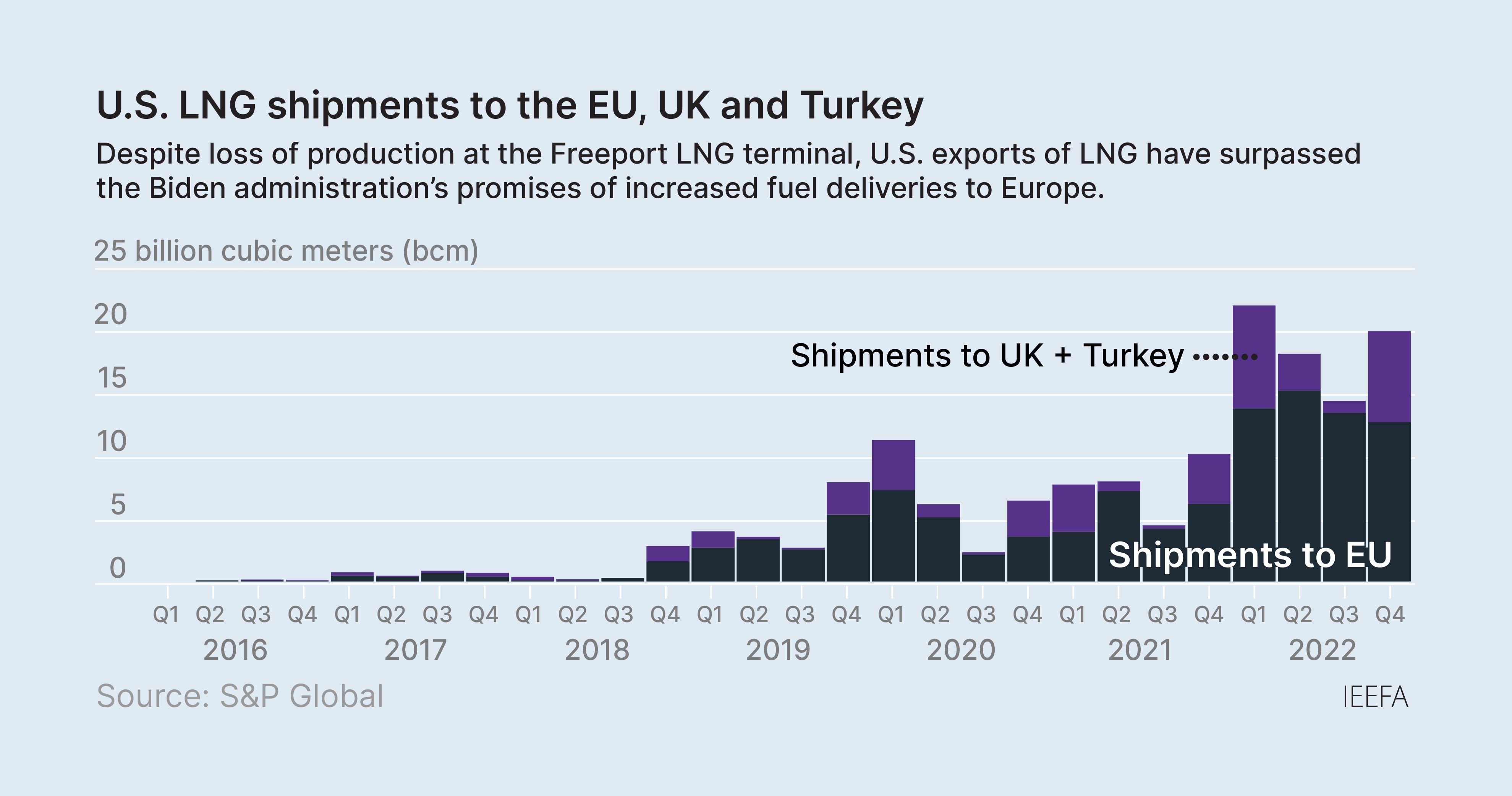

As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was sending shockwaves through Europe’s energy markets last March, the White House announced its support for sending an additional 15 billion cubic meters (bcm) of U.S.-sourced liquefied natural gas (LNG) to the EU by the end of 2022. At the time it seemed like an ambitious goal. In 2021, the U.S. shipped less than 22 bcm of LNG to the EU, so the White House target represented a whopping 70 percent year-over-year increase.

Yet data from the U.S. Department of Energy and S&P Global shows that by mid-August—less than five months after the announcement—European LNG imports had already exceeded the White House target. And for the rest of the year, the U.S. LNG industry watched that seemingly audacious goal recede in the rear-view mirror.

U.S. LNG shipments to Europe fell slightly in the fall as import terminals maxed out, but have now resumed their earlier torrid pace. Although full-year data isn’t available yet, by the end of 2022 total LNG export volumes from the U.S. to EU member states will likely surpass 55 bcm—which is more than two and a half times last year’s level and represents a 34-bcm year-over-year gain, more than double the White House’s target.

The U.S. might actually ship even more LNG to Europe next year than this year

Adding in the UK and Turkey, which aren’t part of the EU but have significant gas pipeline connections to the region, U.S. LNG shipments to greater European gas markets could reach 75 bcm by the end of the year, up by 44 bcm from 2021.

What made all of this even more remarkable was the loss of all output from the Freeport LNG terminal in early June, due to a massive explosion at the Texas plant. At the time, Freeport represented almost 20 percent of total U.S. liquefaction capacity, and it had sent more than three-fifths of its output to Europe in the first part of the year. If Freeport hadn’t blown up, U.S. LNG exports to greater Europe could have topped 80 bcm in 2022.

As dramatic as this shift has been, the U.S. might actually ship even more LNG to Europe next year than this year. One recently completed LNG project, the Calcasieu Pass LNG plant in Louisiana, was just ramping up output at the beginning of 2022. Now that the plant is operating at full capacity, we could see its annual shipments to the EU rise by 4 to 5 bcm in 2023.

The Freeport LNG terminal remains a wildcard. It's taken far longer than expected to get the plant up and running again, and federal regulators recently asked the company to resolve a long list of issues before the plant can reenter service. But if the plant resumes operation in the second quarter of 2023, it could add an additional 1 to 2 bcm to the trans-Atlantic LNG trade over the coming year.

Put simply, the U.S. has shipped more LNG to Europe than virtually anyone thought possible, and could ship even more next year. Yet the lessons here aren’t necessarily what one might think.

First, political intervention played almost no role in any of the increase in U.S. LNG shipments to the EU. The White House has been little more than a cheerleader, watching the game from the sidelines. The real action has been in prices: The key reason that the U.S. LNG industry shipped so much of its product to Europe is that European buyers paid them. European buyers were willing to pay a premium for any LNG cargo they could get. Since U.S. LNG contracts don’t limit where the fuel can be shipped, European buyers snapped up as much as they could. In the process, U.S. LNG companies and traders made boatloads of money, both literally and metaphorically, shipping their wares to Europe.

Companies that place their bets on decades of robust LNG demand could be setting themselves up to lose as much money in a coming bust as they’ve made during this year’s boom.

Second, despite the massive increase in LNG imports, Europe is still short of gas. As U.S. liquefied gas exports to Europe surged, Russia progressively slashed its pipeline gas exports. It’s difficult to know whether the two are linked, yet it’s clear that Russia was using its dominance in the EU gas market to inflict both political and economic pain on its rivals. The result is that Europe is more gas-starved than ever, with total gas consumption falling more than 20 percent year-over-year in the latter portion of 2022. Energy-intensive industries have been particularly hard-hit by the shortfalls.

Third, the dramatic increase in U.S. LNG shipments to Europe was accomplished without building any new gas infrastructure beyond what was already planned at the beginning of the year. Two new U.S. projects were approved in mid-2022, but they won’t be online for years. Germany rushed one new LNG receiving terminal into service in mid-December, but the first cargo isn’t expected until next year. European politicians are considering expansions of gas infrastructure, with plans that analysts are already calling “massively oversized.” But the major gains in LNG imports from the U.S. were accomplished without any new terminals. As it turned out, boosting LNG exports to Europe didn’t actually require new infrastructure. Using existing facilities more efficiently was enough.

A fourth lesson is that the EU’s gain in LNG imports has mostly come at the expense of Asia—particularly developing nations with fragile economies. For example, global traders Eni and Gunvor defaulted on their contracts to deliver LNG to Pakistan at least 11 times since 2021, forcing gas rationing and emergency tenders for more supplies. At this point, sky-high prices and supply glitches have saddled LNG with a reputation as an unreliable and volatile energy source, curbing LNG-to-power plans in Asia and forcing energy forecasters—including Bloomberg, ICIS, and IEA, among others—to slash their projections for Asian LNG demand growth.

Lastly, the EU’s appetite for U.S. LNG is far from guaranteed in the long run. Europe is certainly reeling from limited gas supplies in the short term. But the continent is responding mostly by cutting demand for gas, by using the fuel more efficiently while ramping up substitutes such as wind and solar. Those shifts are likely to last for the long haul, and are being supercharged both by high prices and by the continent’s ambitious climate goals, which call for major cuts in gas consumption. The European economic think tank Bruegel projects that cuts in European gas demand by 2030 could be so steep that most of the continent’s LNG import infrastructure will be unneeded.

In short, the boom in U.S. LNG exports to Europe could be fleeting. Yes, we can expect European demand for LNG to remain high for several years, as the continent adjusts to a new and more fractious relationship with Russia, its former top gas supplier. Prices could remain elevated too, with Europe buying LNG from global spot markets to make up for shortfalls of piped gas. Meanwhile, newly commissioned floating LNG terminals, along with better use of existing gas pipelines, may help ease shortages in eastern and central Europe, where dependence on Russian gas is most acute.

But long-term LNG demand, both in Europe and globally, is far from assured. High gas prices and the advancing global energy transition have already put a dent in global LNG demand growth. Companies that place their bets on decades of robust LNG demand could be setting themselves up to lose as much money in a coming bust as they’ve made during this year’s boom.

Clark Williams-Derry ([email protected]) is an IEEFA energy finance analyst