LNG exports may spell trouble on horizon for U.S. consumers

Key Findings

U.S. consumers could face higher prices as a glut of liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects are built.

The U.S. natural gas industry has plans to export as much as half of the nation’s production to European and Asian markets that are willing to pay more.

The U.S. government’s requirements to ensure that LNG projects are in “the public interest” should be reviewed and updated.

Natural gas prices have fallen by two-thirds since last year. U.S. gas consumers may be breathing a sigh of relief, but they shouldn’t rest easy: A return higher prices could be on the horizon.

The pain is likely to be caused by a tsunami of new liquefied natural gas (LNG) export projects that will open over the next few years.

As the U.S. exports more of its natural gas, the nation is likely to import higher gas prices as a result.

The growth of exports pits overseas natural gas buyers—many of whom are accustomed to paying top dollar for the fuel—into direct competition with U.S. consumers. With only a finite amount of North American gas to go around, bidding wars can boost the price that Americans pay for gas.

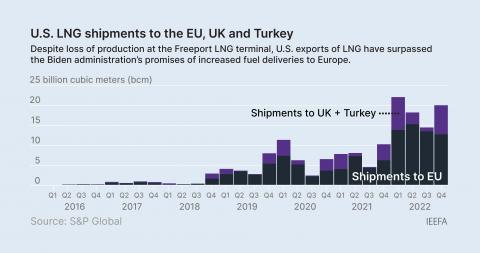

We saw this dynamic unfold last summer. Russia slashed gas exports to Europe during the Ukraine crisis, which sent global gas prices skyrocketing. U.S. gas exporters shipped as much as they could to Europe and Asia—not out of the goodness of their hearts, but in search of higher prices and bigger profits.

The resulting export surge left the country with a natural gas shortage that lifted prices to their highest levels in more than a decade. The gas industry reaped record returns, largely at the expense of Americans who paid more to heat and power their homes.

After last year’s market chaos, natural gas prices have now come back down to earth, both in the U.S. and around the globe. But gas markets are volatile. Another hiccup in global LNG supply, or another disruption of gas pipelines in Europe or Asia could cause international gas prices to skyrocket yet again. And as we now know all too well, price spikes globally can mean higher prices here at home.

Although the U.S. LNG boom began in 2016, it was only last year that we saw exports causing such clear pain for American consumers. That’s because, until recently, America simply couldn’t export much gas. Limited capacity at LNG terminals meant that there was also a limit to how hot the bidding war could get.

But as exports have grown over the past few years, the U.S. has emerged as the world’s top LNG supplier. New export facilities created more price competition for U.S. gas. Today, there are seven operating U.S. LNG terminals that collectively can export 12% of all U.S. gas production. Pipelines to Mexico and Canada export another 10%.

The numbers will go much higher. Three new gas export projects are under construction along the U.S. Gulf Coast. Another LNG plant in Corpus Christi, Texas, is undergoing a major expansion, and Mexico is building two additional projects that will be sourced with U.S. gas. Last month, a terminal developer greenlit another major plant that will begin exporting LNG in 2027. As these projects come online, the nation’s LNG exports will almost double from last year’s levels.

But if the gas industry has its way, that would just be the beginning. Federal regulators have already approved 12 new plants that would redouble America’s already vast LNG export capacity. Other projects are in the early stages of permitting, and still more are on the drawing board.

All told—adding up all the projects that exist or are in the permitting process—the gas industry has plans to export half of America’s current gas production. Adding in pipeline exports of natural gas, including exports to Mexican LNG terminals, gas exports would rise to more than 60% of current output.

Although it’s unlikely that all of those projects will move forward, the projects that are already under construction could create massive headaches for U.S. consumers. Exports are locked into contracts for 20 years. Even if the U.S. gas industry can boost production for a while, it seems exports eventually will lift demand, put pressure on supply, and create price chaos in domestic gas markets.

It’s worth remembering that Australia, one of the world’s top three LNG exporters, has seen this very dynamic play out. As LNG exports on Australia’s east coast rose, domestic shortfalls caused prices to spike, prompting threats of government intervention to keep exports in check.

Luckily, there’s an easy solution here in the U.S. For a gas export project to move forward, the federal government must find that the exports would be in “the public interest.” But the studies that the government relies on to assess public interest are old and deeply flawed. One study finds that higher utility bills aren’t really a problem, for example, because they can make people who own stock in energy companies richer.

Simply raising the bar for whether exports are truly in the public interest would be an easy first step to prevent the market disruptions on the horizon.

It’s high time for America’s natural gas regulators to take a good hard look at whether exporting more and more gas is truly in the best interests of the American public. A careful analysis will likely show that, over the long run, unconstrained gas exports hurt not only American consumers, but also industries that rely on domestic gas supplies.