Oil supermajors are meeting climate goals by selling assets—but still increasing emissions

Key Findings

Although oil companies have claimed that selling assets will offset emissions, they are often only transferring them to new owners who may be releasing even more climate-damaging gases.

A new report found that existing corporate disclosure standards in the EU, UK and U.S. aren’t sufficient for tracking greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel asset sales by supermajor oil companies.

Emissions must not only be measured, but time and attention need to be devoted to suitable public policies and regulatory systems that use the measurements to meet critical climate benchmarks.

The Columbia/Sabin study is an important contribution to the literature on climate change that should be relevant to business leaders, investors, credit agencies, environmental and financial regulators.

The world’s largest oil companies are selling assets, often claiming progress in meeting greenhouse gas reduction pledges. As a seminal new report from Columbia University’s Center on Sustainable Investment and the Sabin Center notes, however, the sales aren’t actually reducing emissions—only transferring them to new owners who may be releasing even more climate-damaging gases.

The report, however, found that existing corporate disclosure standards in the European Union, United Kingdom and United States aren’t sufficient for tracking greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel asset sales by supermajor oil companies. It found (through laborious effort) that many sales resulted in higher greenhouse gas emissions because of purchases by less-efficient operators that often had an even worse track record than the giant oil companies.

Climate change is altering the way we think about science, technology, planning, financing, governing, law and regulation, and even accounting for greenhouse gases. Current accounting tools work to account for the type, size, and value of assets down to the decimal point. Climate change is now requiring that companies adapt these same laser-like accounting tools to greenhouse gases.

The report hammers home the point that emissions must not only be measured, but time and attention need to be devoted to suitable public policies and regulatory systems that use the measurements to meet critical climate benchmarks.

Solid climate policy needs to be built around a uniform system of accounting that manages emissions.

Large investors are becoming aware of the problem. New York City Comptroller Brad Lander, for example, is asking for a careful examination of the metrics used by companies and how those metrics reflect their climate plans and accomplishments. When the head of one of the largest public pension funds in the country wants more attention to the question of how we measure the problem and solutions related to climate change, the issue is now more than just a matter of good public policy. The issue is now about how finance and business need to be conducted going forward.

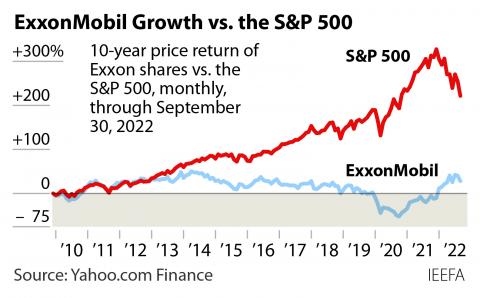

The oil and gas sector once was the leading contributor to Investment funds around the world, but they are now in last place in the stock market. Part of the problem is an inability, and in some cases an unwillingness, to stay ahead of the carbon curve.

The Columbia/Sabin study is an important contribution to the literature on climate change that should be relevant to business leaders, investors, credit agencies, environmental and financial regulators. It has particular relevance to the United States market because the U.S. is behind much of the rest of the world.

This report raises very important questions about direction in climate policy:

- For oil and gas companies: How conscious are oil and gas companies regarding the carbon footprint of their transactions

- Europe has a different approach to economic planning than the U.S. The discussion on the taxonomy and a systematic plan for economic growth is creating new directions in product design, production process planning, and new applications of technologies—all designed to lower the carbon footprint of economic activity.

- Where will support come from in the United States for improved regulatory oversight of these carbon emission issues? Typically, responses are from environmental regulatory agencies but the approach taken by the Columbia/Sabin researchers suggests federal interest should be coming from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, as well as the departments of Commerce, Treasury and Energy.

A debate about the shape of markets and our global economy is taking place in Europe, China and most other major economies. The end of that debate will be a reshaped regulatory framework governed by principles of sustainability. U.S. failure to participate is sending the wrong market signals. Over the long run, the U.S. runs the risk of encouraging businesses and products to be uncompetitive on the global market. These kinds of thoughtful studies are a warning signal that climate change cannot be ignored without serious consequences.