Private equity investments, climate change and fossil-free portfolios

Key Findings

New private equity investments in fossil fuels are out of step with market forces.

Holding fossil fuel investments in a private equity portfolio comes with considerable costs.

As part of a portfolio-wide divestment strategy, reducing private equity investments in fossil fuels is fiduciarily sound.

Opponents of divestment have lately pointed out that institutional fund managers who divest their portfolios of fossil fuels would incur increased complexity and expenses to sell off oil and gas private equity investments. Institutional fund managers looking at divestment need not stumble over this part of a climate solutions strategy.

Here is why:

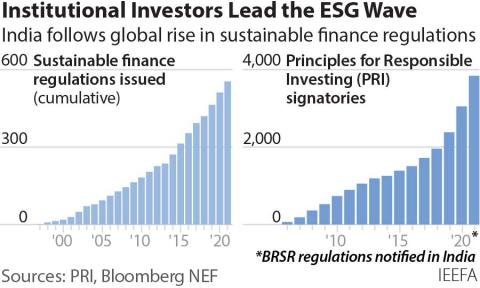

- Investors are telling us that private equity investments in fossil fuels are a mistake. Since 2009, action in the private equity industry has been in healthcare (+14.4% compound annual growth rate or CAGR) and information technology (+13.3% CAGR). McKinsey reports that energy is a last-in-class private equity performer. Since 2009, energy has decreased from 12% of the market to 7% of the private equity market by deal volume. Its negative 1.9% annual growth rate pales against industry leaders.

Warnings like this about the oil and gas industry echo those that surfaced about the coal industry for more than a decade. Despite these warnings on coal, certain investors still put up and lose capital on failed power plant deals.

As an economic indicator, successful private equity investments tell us a company or industry is capable of continued growth, or new ways to integrate and contribute to economic growth.It is difficult to make a financial case for coal, oil and gas in a private equity portfolio.

These fossil fuel industries are not able to integrate into the energy transition without significant change. To date, decarbonization strategies are coming with a lot of promises and small cash flow allocations. Investment fiduciaries who direct money managers to avoid coal, oil and gas make sense.

- Institutional funds need not and should not leave private equity. Private equity should leave fossil fuels.

Some, like the Oregon treasurer and his allies, have gone so far as to project a ruinous impact from divestment because they claim getting rid of fossil fuels from private equity would equate to eliminating private equity as an asset class altogether. Since private equity has generally produced strong returns, its elimination from a portfolio would drag down the earnings of an entire pension fund.

The above indicators regarding the declining significance of fossil fuels, however, turn the table on such arguments.

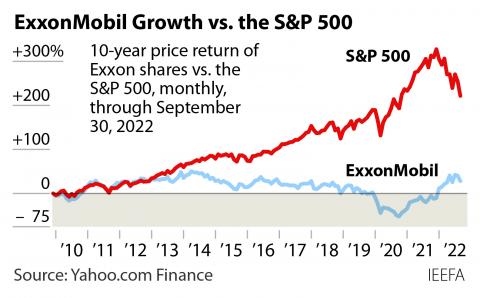

People who watch the energy markets closely know that for more than a decade, the industry has performed poorly. Although the oil and gas industry was king in the 1980s, today it commands only a fraction of its original share of the market. The path ahead for oil and gas is bumpy and volatile. The most recent upswing in oil prices was propelled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The high prices brought banner profits for private companies and sustained Russia’s war effort. Oil and gas companies catapulted to No. 1 in the stock market in 2022. Yet no sooner had the headlines announcing the industry’s stellar 2022 performance hit than the stocks tanked. By the second week of February, oil and gas stocks fell to the bottom once again.

Since then, the energy sector has been locked in a competition with healthcare and utilities for last place.

Opponents of divestment have a point that getting rid of coal, oil and gas assets prior to the planned exit strategies is likely to lead to losses. They are right—but for the wrong reasons. Private equity is supposed to capture value that enhances the basic investment targets of a pension or endowment. Institutional funds that currently hold fossil fuel investments in private equity, however, are likely to be holding assets that are below book value. The investments are not going to fare any better at the planned exit date. The argument that divesting will lead to losses is specious because these investments are losing value due to larger market forces. Fossil fuel investments act as a drag on portfolio returns. The longer they are held, the less they are worth (barring another invasion).

Lagging investments in a private equity fund are a particular problem for public pension fund managers. They got into the private equity world as an alternative to traditional equities and bonds. Standard asset allocation at the time is no longer generating sufficient profits to support public worker pension benefits. When a stock and bond portfolio fails, government budgets must reduce salaries of public workers or raise taxes from the general population to pay for the pensions.

- A prudent strategy for private equity is to not invest in any new fossil fuel investments and to watch and wait for the earliest opportunity to exit an existing investment with minimum losses, or possibly taking gains. Although getting rid of existing fossil fuel investments in existing private equity portfolios may have to wait, the wisdom of waiting would not be because of financial losses—those losses are, as the saying goes, already baked into the deal. Waiting and watching may be the better way to cut losses, but buying into any new fossil fuel investments rewards last-in-class investment performance.

Many of the funds that oppose divestment from fossil fuels generally divested from Russian stocks due to objections over Russia’s invasion. Here, the funds demonstrated a certain moral clarity but not much financial acuity. A significant reason, if not the major reason for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was linked to oil and gas interests. Russia’s petro-kleptocracy is held up in large part by a historically imperiled fossil fuel industry. The economic foundation of Russia is oil and gas. It can be temporarily held together with favors from friends and strains among its adversaries, but the fundamentals—the fortunes of the fossil fuel sector—are in decline. The winds of economic change are benefiting the sustainable calculus.

In the end, arguing against fossil fuel divestment because it requires an unwinding of existing illiquid private equity deals misses the fundamental financial point: These investments—whether in stocks, bonds, private equity, real assets or real estate—are a drag on portfolio performance wherever and whenever they are being made. The complexity they bring with regard to divestment is just part of the burden they create on overall portfolio management. For an industry with declining market share, volatile pricing, and short-term unsustainable price hikes that are dependent on moral atrocities, do the benefits of holding these stocks outweigh the risks?

These are the calculations that lead to the question: Why invest in oil and gas at all? From the looks of things, the private equity world is already on its way out—why are some investment and pension fund managers so behind the curve, and why are they throwing good money after bad?