Oil and gas profits driven by Ukraine conflict, not financial skill

Key Findings

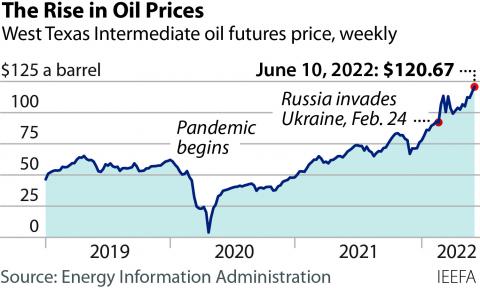

Ukraine invasion is driving high oil prices and inflation

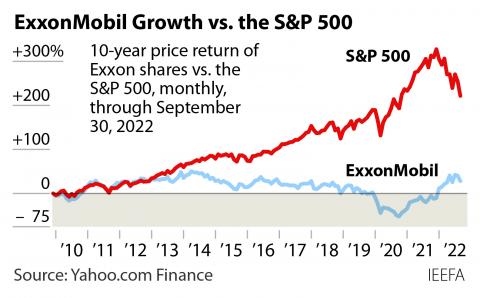

Higher profits have caused investors to forget about fundamental

The current bonanza for oil and gas companies is unsustainable

The oil and gas sector’s strong profits are accompanied by a dance in the dark between stock analysts and oil and gas CEOs. It ignores the war in Ukraine as the driver of high oil prices and allows industry leaders to reclaim their mantle as Masters of the Universe. But the business dynamics of the sector are unsound financially. Instead, the new universe is being led by a Russian president who is driven by the need for higher revenues to finance a war.

Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank, has identified high energy prices and structural bottlenecks caused by Russia’s Ukrainian invasion as a key cause of inflation. Her financial assessment was accompanied by a geopolitical perspective that was delivered in the starkest terms about the Russian invasion.

Seeing Russia as a purveyor of state terrorism, she excoriated the “sick” impulses behind the wholesale destruction of Ukraine and its people. Lagarde is stepping way outside her role as a referee of the economy to bring attention to the extraordinary negative financial imbalances created by the invasion on the economy.

Two weeks ago, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) held an international gathering of climate analysts and activists in New York City. Svitlana Romanko, a university professor-turned-international climate activist, attended from the Ukraine.

She had an urgent plea for the world not to forget that the war continues each day. Her work with Ukrainian environmentalists and internationally is aimed at a green rebuilding of Ukraine. This is not just hope in a dark time, but a sound business strategy for redeveloping cities, infrastructure and new industries.

“If we want to put the lessons of this war into action, we must halt all fossil fuel expansion and countries everywhere must commit to the rapid and just transition away from fossil fuels,” she said. “Reliance on coal, oil and gas is the intentional embrace of death, misery and collapse in Ukraine and at a global scale.”

Record prices boost profits

Last week, the oil companies released their earnings reports. Exxon’s profits were the highest ever. The price of oil through the third quarter of 2021 was $73 per barrel, but it spiked to on average $100/barrel one year later. Earlier in the year, the price of Brent hit $129 per barrel. European natural gas prices tripled, and U.S. Henry Hub gas prices leaped from $3.33 per million British thermal units (MMBtu) to more than $8.20 MMBtu—a 146 percent increase—during the same period.

Overall revenues for ExxonMobil rose from $200 billion in the third quarter of 2021 to $318 billion .

This is not a typical business cycle at work. It is expert spin cycle work.

ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods attributed the stellar financial performance to well-managed revenue, controlled costs and wise asset allocation—but said not a word about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a driver of rising oil prices or lucrative bottlenecks. Analysts didn’t ask about the underlying causes of ExxonMobil’s record-setting quarter. The pattern was followed at a Chevron call for analysts, as well.

The Wall Street Journal’s Colin Eaton had the temerity to suggest that the “war in Ukraine caused a spike in energy prices” that benefitted the two companies. But Chevron CEO Mike Wirth took umbrage at the challenge to the propriety of their current profits. He argued that the oil and gas companies have come through bad times and it is unfair to begrudge the companies their due now that they are reaping the benefits of their long-term investment strategies,

Wirth has it wrong. This is not a typical business cycle at work. It is expert spin cycle work.

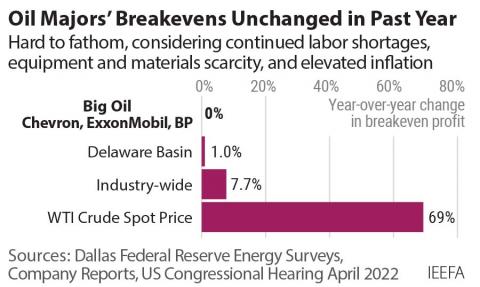

The long-term investment trajectory of the oil and gas industry produced a decade of poor performance prior to the invasion. The forces that created the bad times were an oversupply, and price collapse of oil and gas from the technological success of fracking. Market share encroachments in the electricity, motor vehicle and petrochemical sectors are altering capital allocation toward alternatives. Even Woods sees the end of ExxonMobil’s gasoline business by 2040 from electric vehicle expansion. The frackers have turned down the volume spigot a bit to mitigate oversupply, but structural forces confronting the oil and gas industry remain.

Two outside forces—the rise in prices from the uneven economic recovery from the pandemic and the brutality of the Ukrainian invasion—drove prices up, not some masterful orchestration of supply and demand by oil and gas leaders. The invasion is political, with profound human and economic consequences. If the prices remain high, markets are capable of moving more rapidly to alternatives, a significant risk faced by oil-producing companies and nations.

Wirth is talking about “good times.” But good for who?

It is no accident that the rising stock prices of the oil and gas sector come as the rest of the stock market has stumbled badly. Lagarde has it right. The rising oil prices have contributed mightily to an economy-wide inflationary spiral, reminding us that the use of oil and gas remains a costly, volatile economic input.

Today, Vladimir Putin is the rainmaker for the oil and gas sector. Squeezing every last euro, dollar, ruble, and renminbi out of the remaining oil and gas reserves is the goal of oil producers as concern over climate change clouds their future. Putin also sees that colonial conquests can reap control of new markets and solidify a realignment of national interests.

His high-wire act is disgraceful. It is also unsustainable.

Lagarde is also right to accompany her sound business analysis with a statement of the geopolitical realities that are driving the market. The oil majors must get beyond their distorted spin on energy market conditions. The companies need to prepare responsibly for the end of the war and the continued shrinking of the oil and gas market.

Keeping prices high through war and devastation has amassed billions for oil and gas interests, but there is a certain dark sickness to the studied silence from those trained to treat ideas and information critically.