Is the oil industry really keeping inflation in check? Huge profits suggest not

Key Findings

Oil industry executives complain about rising drilling costs but their responses to breakeven profitability questions downplay the cyclical impacts of their industry

Six executives told Congress they needed between oil prices between $30 and $45 per barrel to break even

The executives claim oil and gas drilling costs are rising only modestly, but the companies are recording huge profits

Industry executives told Congress last April that oil prices had to be at a certain level for them to make money drilling new wells. For Devon Energy, it was “slightly above $30” per barrel. ExxonMobil said $35. BP’s number was $45. Chevron estimated “about $40.” Shell and Pioneer Natural Resources agreed on $30.

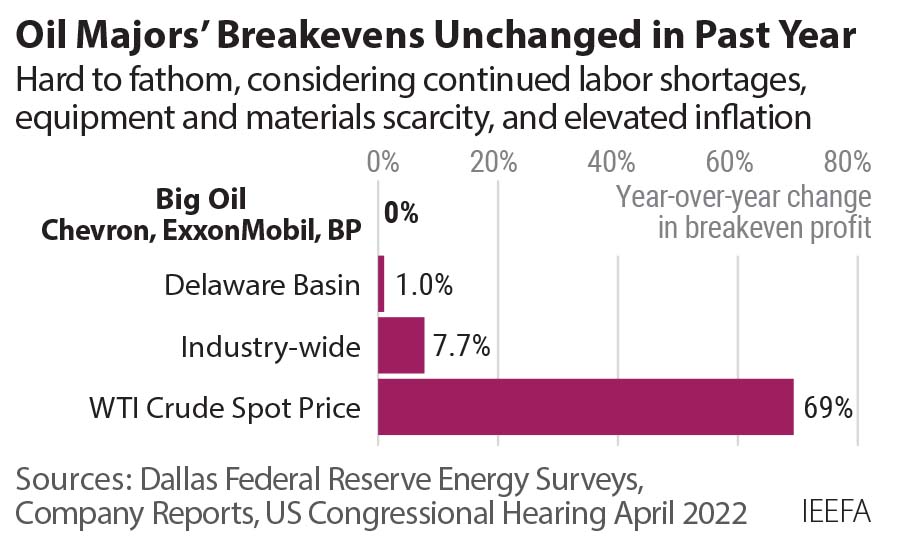

The answers were somewhat surprising, given that a Dallas Federal Reserve study taken only days earlier had found a larger sample of oil companies needed prices to be at $56 per barrel before drilling was profitable. A year earlier, survey respondents had reported an average of $52 per barrel. The survey results suggested that drilling costs rose only about 8% between 2021 and 2022—roughly on pace with overall inflation—even as oil prices ballooned by 69%.

What can we learn from all this? First, large producers claim to have much lower breakeven points than the industry as a whole. (Our research into ExxonMobil has called this idea into question.) Second, and more importantly, executives claim that oil and gas drilling costs have increased only modestly, yet oil company revenues have skyrocketed, resulting in huge profits—ultimately at the expense of the consumer.

Across regions, average breakeven prices to profitably drill a new well vary. The Permian Basin, straddling Texas and New Mexico, offers relatively low breakevens. According to the Dallas Fed survey, the Permian’s Delaware sub-basin edged out the Midland region (another Permian sub-basin) as the host to the lowest average breakevens in the Permian. Delaware breakevens stood at $49.74 per barrel in 2022, just 1% higher than the prior year.

ExxonMobil and Chevron, large operators in the Delaware, pointed to productivity gains and investments in front-end infrastructure such as a central processing facility and centralized tank batteries that mitigated the worst effects of inflation.

In the Dallas Fed survey responses, we saw oil and gas executives complain about rising costs and supply chain woes: Labor shortages, scarce equipment, oilfield service fee inflation, and so on. Yet somehow, the woes barely factored into the industry’s estimates of drilling costs.

There’s an obvious conflict here. On the one hand, oil and gas executives protest bitterly about rising costs. But when it comes to reporting breakeven prices, they claim they’ve been largely successful in defying inflationary pressures.

In their most recent quarterly earnings conference calls, executives from both Chevron and ExxonMobil discussed their outlook on inflation. Chevron Chief Financial Officer Pierre Breber said, “on the onshore U.S., we have seen cost inflation in the single digits. We have been able to mitigate a part of that through good planning, smart procurement, and good relationships with suppliers.” Kathryn Mikells, ExxonMobil’s chief financial officer, said executives feel “really good about how we are managing inflation to date. Our overall structural cost savings, kind of plan and program, is very much on track.”

Perhaps this confidence is overblown. The oil and gas industry initially was slow to acknowledge the effects that supply chain disruptions would have on their operations. Now, cognitive biases, such as optimism bias or anchoring to projections, could be bending their cost estimates downward.

If this is another case of oil and gas executives being slow to recognize a key financial trend, then watch out for future financial results from the oil patch. Delaware Basin producers in particular have the most room for upward adjustments to their breakeven estimates for profitability.