Key Findings

The rationale for recent coalmine approvals has been: “If we don’t supply, other countries with lower emissions standards than ours will step in.” The reality is quite different.

The three exporting mines approved this week represent a significant slice of NSW’s coal production, at 17%, and are long-lived, extending mine operations well beyond 2030.

Increasing supply over the long term into a market with declining demand for Australia’s thermal coal exports places these and other mines at increasing risk of financial stress.

Introduction

The federal government has approved three thermal coalmine extensions in NSW, with

a collective capacity of 39 million tonnes a year (mtpa) of coal extraction, representing

17% of NSW coal production in FY2024.

The Narrabri South underground, Ravensworth underground and Mount Pleasant open-cut mines all contain methane gas. They have been approved on an unabated and unrestricted basis, meaning fugitive methane emissions, beyond some partial flaring measures, will be released to the atmosphere.

This puts Australia at odds with global climate change ambitions. An International Energy Agency (IEA) report, published this week, outlined a roadmap for fossil fuel production relative to full implementation of COP28 commitments.

The IEA says, “No technological breakthroughs are required to achieve the 75% cut in methane emissions from fossil fuel operations to 2030.” Methane mitigation in coalmining is already possible. Beyond that, demand reduction for the fuels should be a priority – in particular reductions in coal supply from surface mines that produce steam (thermal) coal.

The IEA had an aspirational message for governments that, “policy and regulation will be critical to remove or mitigate obstacles that prevent companies from getting started and going further”.

Australia’s Coal Export Trade Dynamics

Coal export trade from Australia is undergoing significant change, and has recently deteriorated in key markets.

China has overtaken Japan for the first time as Australia’s largest thermal coal export destination. In the first half of 2024, Australia exported 34.7mt to China, 35% of total thermal exports, according to Trade Map data.

Sales of thermal coal to China rebounded following the lifting of trade restrictions in early 2023.

The Trade Map data indicates our traditional coal markets declined – all except China. Exports to our premium coal markets of Japan, Korea and Taiwan (JKT) fell by 11% in FY2024, following a 24% decrease in FY2023. This market for Australia’s premium thermal coal is in permanent decline. Exports to the South-East Asia market had plateaued. In all, excluding China, thermal coal exports from Australia fell by 10% in FY2024.

China has been the major growth market for Australia. But recently, it diversified its metallurgical (met) coal supplies away from Australia, and is following suit with thermal coal, by bolstering domestic coal production with a massive pipeline of new coalmines.

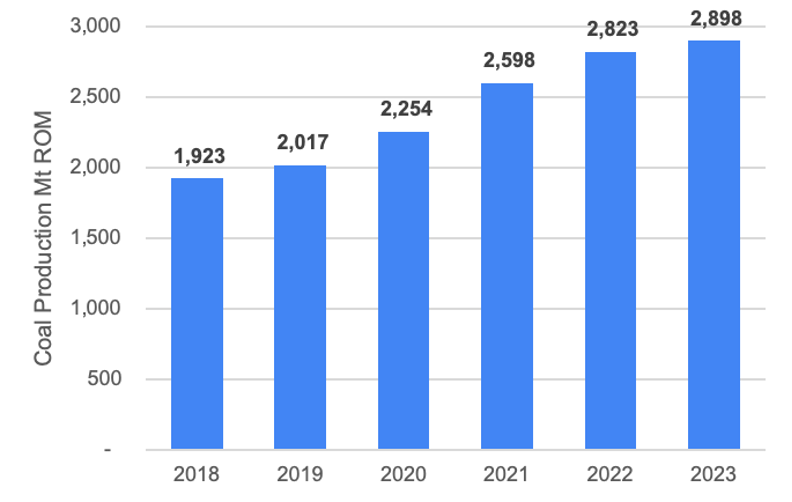

China has approved new coalmines with a collective annual capacity of 1.2 billion tonnes. This capacity will take time to develop. China’s long-term vision is to cease imports by bolstering domestic production levels. It has grown domestic production by nearly 1 billion tonnes in the past five years (Figure 1), and could replicate that by 2030.

Figure 1: China’s domestic coal mine production trend

Source: GEM Global Coal Mine Tracker

There will be ebbs and flows in coal exports from Australia to 2030 but beyond that the message is overwhelmingly clear. Australia’s newly approved coalmining capacity of 39 million tonnes will need to compete on a far grander scale, risking increased financial stress to their prospects.

Methane emissions in coalmining

In underground mining, the main source of methane emissions is of low concentration methane present in the air ventilated throughout the mine, known as ventilation air methane (VAM). This can be abated by oxidising the VAM rather than merely venting it to the atmosphere.

In contrast to Australia, China’s proposed coalmining regulations would reduce methane emissions in the coalmine. For example, it would compel miners to “process coalmine gas with a concentration of 8% or less and ventilation air methane using flameless oxidation technology to produce heat for power generation”.

Capture of methane from gas drainage before and during mining at Australian underground mines is anticipated, as it is required for safety reasons. Some of the captured methane can be burned in flares to form less potent carbon dioxide, although only a relatively small volume of the total. More effectively, concentrating and utilising the gas for heating, power generation and gas sales is a more comprehensive abatement. There are complexities involved but essentially comprehensive abatement is not required in the Narrabri or Ravensworth underground mine approvals.

For open-cut mines, such as Mount Pleasant in the NSW Hunter Valley, mitigation would require pre-drainage of coal-seam gas in gas-rich areas before mining each section. The captured gas could then be utilised.

This is a costly exercise for miners. It also adds operational complexity as it requires planning and lead time for sequencing in advance of mining. Additionally, the quantity and quality of gas captured may be insufficient to warrant large investments in mitigation.

Given these complexities, methane mitigation is generally not economically feasible. In Queensland, several coalmines have been awarded funding for methane abatement projects. While some argue governments should not fund or subsidise coalmines, in reality it is the only way to kick-start and maintain such projects.

The federal government hopes the Safeguard Mechanism will reduce emissions in coalmining, among other sectors. But coalminers are not investing in mitigating fugitive methane emissions, without subsidies. Without economic viability, or strict requirements on mitigation, miners will instead rely on purchasing or surrendering carbon credits to offset their emissions.

If not stop then limit

The three mines approved now have long lives, up to 2044 in one case and well beyond 2030. If these approvals do not require methane mitigation, other limits on scale should be imposed.

Perhaps a sunset timeline. With demand for Australia’s high-energy coal in terminal decline, at some point it will be insufficient to support mines’ viability. While it’s unclear if the export market will reach this tipping point by 2030, it will likely arrive during the extended lives of these mines.

Supply versus demand is not the only issue. Coalmines’ emissions intensities are set to continue to grow into the future as more and more methane is emitted per tonne of coal produced.

For example, according to the NSW IPC 2022 report on the Narrabri South extension, “beyond 2032 methane emissions will increase to about double of current levels (i.e. 30% to 40% CH4 [methane] compared with 5%-25% in the northern [existing] mine)”.

By approving mines on an unmitigated and open-ended basis, governments are locking in higher emissions intensities for longer – well into the post-2030 period.

As the mining projects extend into deeper and more gaseous reserves, the problem will only increase. The government risks enabling an increase in future liabilities for fugitive emissions, rather than setting them on a downward trajectory.

Lower extraction limits could be part of the solution. The mine plans presented for approval are overly optimistic. For example, the Narrabri UG mine in northern NSW has achieved 5mt run-of-mine (ROM) production averaged over the past two years. Seeking approval for 11mtpa, more than double this rate, is unrealistic. The mine has been plagued by geological and equipment reliability issues, and now must contend with gas management.

Similarly for open-cut mines, by approving optimistic mine extraction rates, such as 21mtpa for Mount Pleasant. It achieved 10.7mt of ROM production average over the past two years yet has sought approval to double this amount. More generally, the mega open-cut mines in NSW grew production by 19% in FY2024, flexing their production within their higher approved extraction limits, all the while increasing their emissions intensity rates. Hence the new approvals risk intensifying future coalmine emissions.

The government has defended its decision to approve these mines, arguing if Australia doesn’t approve the mines, then other countries, with lower emissions standards will step in. That’s a bit rich when no such standards apply here. What's more, the very countries claimed to lack these standards, such as China, are looking to tighten requirements to mitigate methane emissions in coalmining.