Navigating the many faces of Indonesia’s energy transition schemes

Download Full Report

View Press Release

Key Findings

Indonesia is moving ahead with at least five energy transition schemes at the same time, as of the time of the report release. The Indonesian energy transition mechanism (ETM) is not a simple one-track endeavor.

At the crux of the matter is the need to free up both capacity and capital; to begin re-engineering Indonesia’s power systems; embrace new and efficient technologies; and build a cleaner, more resilient system in the long run.

For Indonesia to fully benefit from the new global initiatives on energy transition financing, IEEFA has included a few recommendations on the key steps along with a checklist in this report.

Executive Summary

The much-anticipated G20 Leaders’ Summit hosted by Indonesia last month has come to an end. Participants reached a Leaders’ Declaration and signed numerous memorandums of understanding (MOUs) on important sectors, such as energy. These MOUs include agreements on the biggest climate deal ever reached, the US$20 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP).

Well before the 15-16 November summit, the Indonesian government had been stepping up its game to switch to a lower-carbon economy. In the past year alone, authorities had announced many changes and new political commitments on climate. From an updated Nationally Determined Contributions target, to the creation of umbrella regulation on a new carbon price scheme, and a Presidential Regulation reaffirming the country’s ambition to accelerate early coal retirement, the government of Indonesia has displayed dedicated efforts to lay the groundwork for this transition.

The hard work has paid off. A few weeks ago at the Bali summit, the G7 International Partners Group (IPG) committed US$20 billion to help Indonesia move away from fossil fuel energy. In addition to this JETP deal, the Climate Investment Funds is allocating US$500 million concessional financing under its Accelerating Coal Transition (CIF-ACT) program to support the faster retirement of coal-fired power plants (CFPPs).

Multiple MOUs and cooperation agreements were signed during the G20 events. It is a challenge for many to track what has been agreed and signed, and who will provide the money. Some questions arise. Which energy transition proposals ultimately moved ahead? What are the details of these schemes? How do they meet the targets proposed? And how will it all be financed?

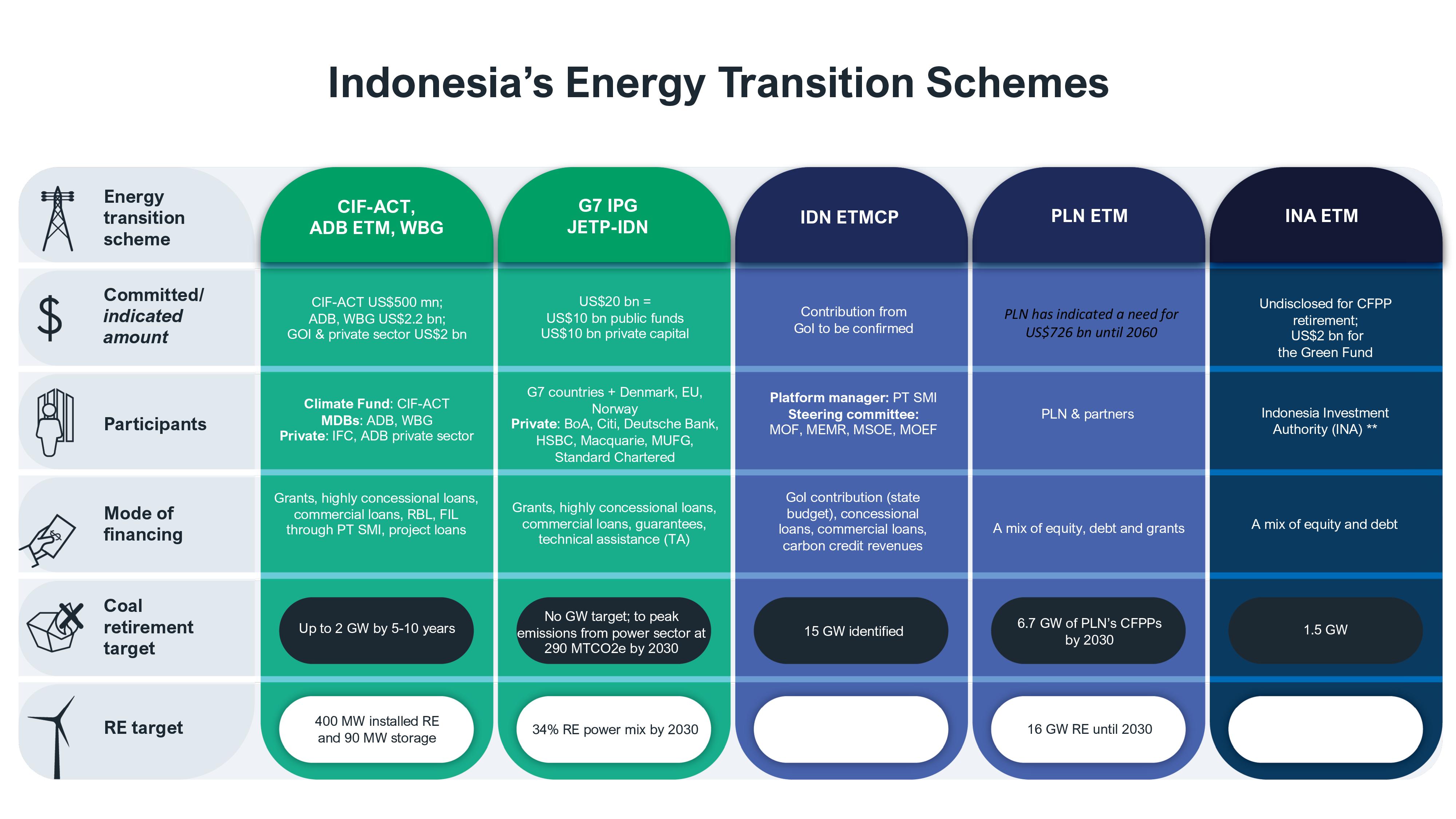

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) acknowledges that, as it stands, Indonesia is moving ahead with at least five energy transition schemes at the same time. These are the CIF-ACT program, which works in tandem with the Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) energy transition mechanism (ETM) and the World Bank Group (WBG); the G7 International Partners Group’s (IPG) Just Energy Transition Partnership for Indonesia (JETP-IDN); Indonesia’s ETM Country Platform (ETMCP); state utility Perusahaan Listrik Negara’s (PLN) own version of its ETM; and the Indonesian Investment Authority’s (INA) ETM.

From all the schemes, at least three transactions have been proposed on early coal retirement and announced to the public.

- The 660 MW Cirebon-1 coal-fired power plant (CFPP), an independent power producer (IPP) refinancing deal led by PLN, ADB, PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur (PT SMI) as the ETMCP, and INA;

- The 1,080 MW Pelabuhan Ratu CFPP, an asset spin-off led by PLN and PT Bukit Asam (PTBA); and

- The 2,640 MW Tanjung Jati B’s 1-4 CFPPs, which Sumitomo Corporation will forgo early and swap with PLN in return for the latter’s 9 GW Kayan hydroelectric project.

Although the progress is commendable, IEEFA will highlight in this report several issues and risks pertinent to the schemes and transactions. The lack of a governance structure will be considered, as will the risk of changes in political commitment, insufficient regulatory and administrative capacity, and absence of transparent data to guide the selection of early coal retirement and renewable infrastructure procurement.

Furthermore, this paper will compare and contrast each of the five schemes and assess their primary components. The appendix presents a summary table comparing the schemes side by side. Since many of the details are still being developed, IEEFA acknowledges a need to keep the appendix as a living document, to be updated whenever a new agreement is reached.

For Indonesia to realize the full benefits of the available global financing initiatives, there are key steps to follow. IEEFA will explain in this report the need to prepare the right policy framework which would unlock barriers to new developments in the renewable energy sector; to optimize Indonesia’s outdated power systems by referring to globally accepted standards; to pilot efficient and economical innovations and techniques in power infrastructure which would create new markets and boost local manufacturing demand; and to align with the financial community’s expectations and requests for the conduct of this transition.

Finally, this paper will raise a number of issues on the IEEFA watch list that would warrant further study:

- How will the selection for early coal retirement and renewable energy procurement be carried out? Will it be inclusive with an adequate level of transparency?

- How will the government of Indonesia address any unforeseen political risks? What support will be given to create a transparent and consistent policy framework, instead of piecemeal solutions, that will tackle problems in their entirety?

- How can PLN improve its system resiliency to reduce repayment risks?

- How should the different financing modalities be structured to achieve optimum outcomes? What would a good governance structure look like?

- How will the carbon emissions associated with a coal retirement transaction be handled?

Each scheme comes with its own targets, participants and financing modalities. The many elements involved show that the Indonesian ETM is not a simple one-track endeavor. It is multitrack, multifaceted and driven by multiple players, and will unfold over a number of years. An important feature is that these efforts, though separate, are not stand-alone platforms, but rather they complement one another in working toward the goal of a faster energy transition.