Governance challenges in Indonesia’s energy transition

Breaking down the many facets of Indonesia’s energy transition schemes including the hallmark US$20 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP)

Billion-dollar climate investments in Asian countries have made headlines in the wake of the Sharm el-Sheikh Climate Change Conference (COP27) and the G20 Leaders’ Summit in Bali, such as Indonesia’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) and Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) Country Platform. A new report by Elrika Hamdi, Energy Finance Analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), addresses the opportunities and risks behind the many faces of Indonesia’s energy transition plans, as well as the country’s path toward energy sustainability, affordability and independence.

“Any plan to transition means retiring fossil fuel sources and investing in renewable energy generation, storageand distribution systems within a minimal budget and time,” says Hamdi.

“Indonesia’s energy transition is about freeing up grid capacity and capital to embrace new technologies and re-engineer the national power systems for the long run.”

Weighing national and multilateral energy transition plans

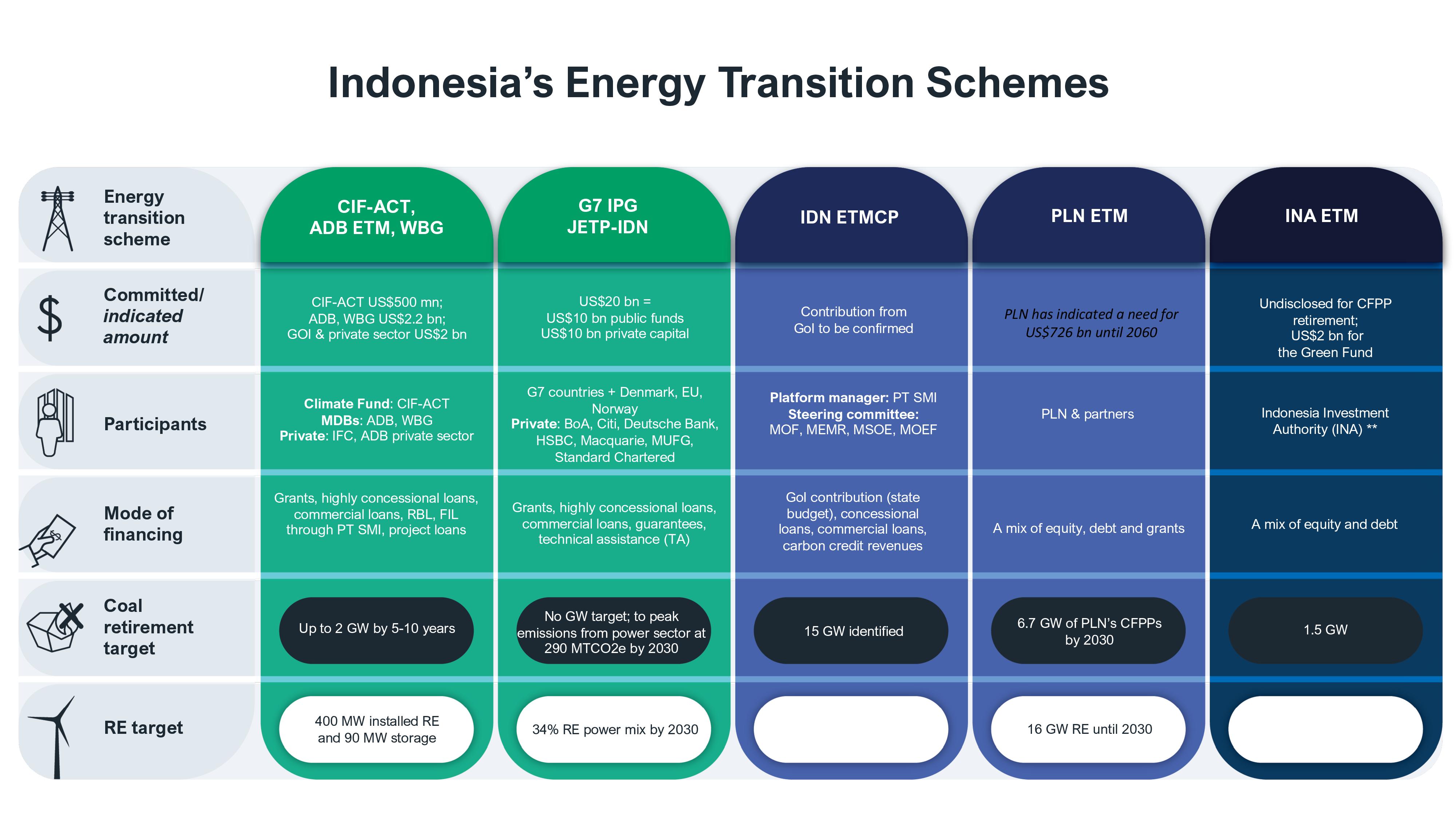

Hamdi analyzes the strengths and weaknesses of the five schemes that will proceed in the months and years ahead: three separate plans backed by international proponents, one put forth by national utility Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN), and the fifth, led by the Indonesian Investment Authority (INA).

One of the globally backed schemes is the Climate Investment Fund’s Accelerating Coal Transition (CIF-ACT) program, which aims to accelerate coal retirement in Indonesia by five to 10 years with US$500 million. It hopes to catalyze up to an additional US$2.2 billion from multilateral development banks (MDBs) including Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank Group (WBG), and US$1.3 billion from commercial and private funding. CIF-ACT’s current investment plan contains roughly 0.4% in grants, while 99.6% are loans.

“While the concessional lending terms will be favorable compared to typical commercial lending, emerging countries like Indonesia would benefit more from higher portions of grant funding, especially in non-commercial areas, such as education and social support for affected communities,” says Hamdi.

Another globally backed scheme, the US$20 billion JETP for Indonesia, is one of the biggest climate deals ever reached.

“The next six months will be the most crucial window to decide the fine print,” says Hamdi. “The public will be monitoring this and hopes are high for the process to be as inclusive as possible through numerous public consultations.”

Meanwhile, the Indonesian ETM Country Platform (ETMCP) is expected to raise funding from the CIF-ACT-MDB collaboration and from private capital and revenues earned from a planned carbon credit mechanism. The ETMCP will be the central platform for any transactions requiring the government’s facilities, such as government guarantees, public-private partnerships or other incentives.

PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur (PT SMI), a special vehicle of the Ministry of Finance, will act as the fund manager and the national focal point of ETM activities.

PLN, the state utility, proposed three options early last month to retire some of its CFPPs, all of which are undergoing negotiations, with no details yet on which coal plants might be retired or cancelled.

Energy transition endeavors led by INA have also been progressing under joint projects, including the early retirement of the Cirebon-1 Coal-fired Power Plant in West Java and the establishment of a US$2 billion green fund focusing on electric vehicles.

“Their leverage as a sovereign wealth fund is in having their own capital, enabling them to go faster. In addition, they can also tap into other sources of funds and countries that might not have been included in the other schemes,” says Hamdi.

Maximizing ETM opportunities

Indonesia’s multitrack mechanism proves that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to the energy transition. However, Hamdi stresses that now is the time to secure a well-prepared and consistent policy framework for good governance, transparency and accountability.

“Considering the long lead time of each transition project, the biggest challenge will be to ensure long-term transparency, accountability and political commitment – all of which are equally important,” she says. “It is about delivering the best value for investors, the country, and the planet.”

For Indonesia to get the full benefits of these global ETM initiatives, Hamdi outlines a few steps – to “prepare, optimize, pilot and align” — starting with upscaling the renewable sector with technical, financial and human resources.

Examples include a greater public disclosure of data and analytics to build stakeholder confidence, and a phaseout of uneconomic CFPPs in favor of cost-effective renewables and storage solutions to improve grid efficiency.

This is about “optimizing”: improving system resilience to reduce repayment risks and supporting the most cost-effective grid options.

A resilient system can integrate storage, manage variability and respond to electricity demand, as well as reduce curtailment risks, a deliberate reduction in power output to maintain the grid’s balance that is typically done for intermittent renewables. This translates into fewer repayment risks for lenders, which may lower the cost of debt, says Hamdi.

The step of “piloting” comes next, to unlock green capital via new and efficient technologies, such as smart grids, storage and e-mobility. PLN’s current oversupply on the Java-Bali grid provides an unparalleled opportunity to pilot renewable power generation.

“However, there has been no clear timeline for renewable and storage project procurement – a legacy issue that many private investors have been anxiously waiting for,” says Hamdi. “Historically, bidding and negotiating with PLN has also taken time and patience, which could be unappealing for investors.”

This is where “aligning” is important: building market confidence should start by matching expectations and plans with investors’ requests. Prudent use of the transition funds needs to take top priority.

Hamdi’s report includes a watchlist: a good governance structure to support unforeseen political and implementation risks, an inclusive and transparent selection process for early coal retirement and renewables procurement, details on the financing structure and modalities, and the treatment of emission credits.

“Considering carbon credit revenues are expected to contribute significantly to the ETMCP, and that the ultimate goal of all the schemes is to reduce emissions, the assignment and approaches taken toward carbon accounting will be important to watch,” says Hamdi.

Read the report: Navigating the many faces of Indonesia's energy transition schemes

Author contact:

Elrika Hamdi ([email protected])

Media contact:

Josielyn Manuel (jmanuel@ieefa.org)