Mapping coal phaseouts in key Asian markets

Key Findings

Despite pledges to decarbonize, China, Japan, South Korea, and Indonesia have all increased coal-fired capacity since 2020.

However, low utilization rates of coal plants in these countries imply an overbuild of coal capacity with substantial room to retire the oldest, least efficient plants.

The rapid renewables buildout in China, Japan, South Korea, and Indonesia will further erode the share of coal generation in the power mix.

Asia, the world’s largest continent, is home to the biggest fleet of coal plants, burning the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel.

China, Japan, South Korea, and Indonesia, housing more than a quarter of the global population, have all increased coal power capacity since 2020. Their additions account for 57% of the world’s 2024 coal-fired capacity of 2,143 gigawatts (GW). China alone, for example, is adding 95GW capacity – equaling almost half of the European Union’s (EU) total coal fleet and 55% of the U.S.

Despite capacity addition, the utilization hours of the coal plants have fallen across all four countries, highlighting the potential to shut down inefficient plants. At the same time, each country has increased its share of energy generated from renewables. The new plants could run for lower hours, and rapid renewable energy (RE) buildouts could be prioritized. Solar and wind, in particular, are cheap and quickly deployable energy sources.

Given each country’s diverse economic structures and energy policies, scaling finance and managing risks for coal phaseouts means negotiating different priorities and pathways. The rapid buildout of renewables in these countries will further erode the share of coal generation in the power mix.

Changes in fossil and renewable energy 2020-23/24

Coal has remained a stubborn component in each country’s national energy supply. China and Indonesia remain the most coal-dominant, with over half of all energy sourced from the fuel. Japan and South Korea rely mainly on imported fossil fuels, doing little to reduce coal reliance. Coal use has remained unchanged and is at the core of the generation mix in both countries. The use of liquefied natural gas (LNG) varies due to its fluctuating high cost; however, it has remained relatively unaffected.

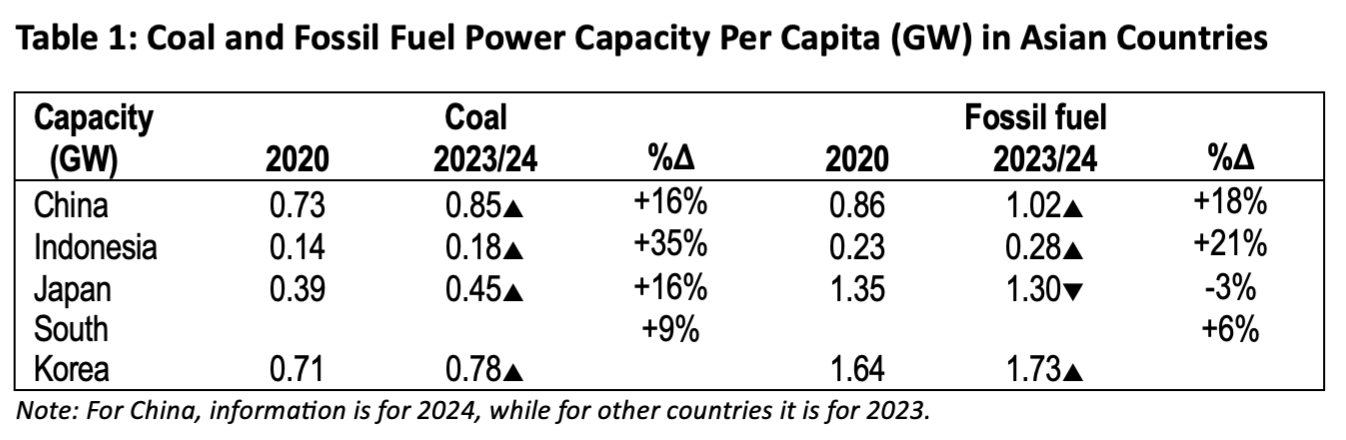

Despite pledges to decarbonize in all four countries, coal-fired capacity has increased (Table 1).

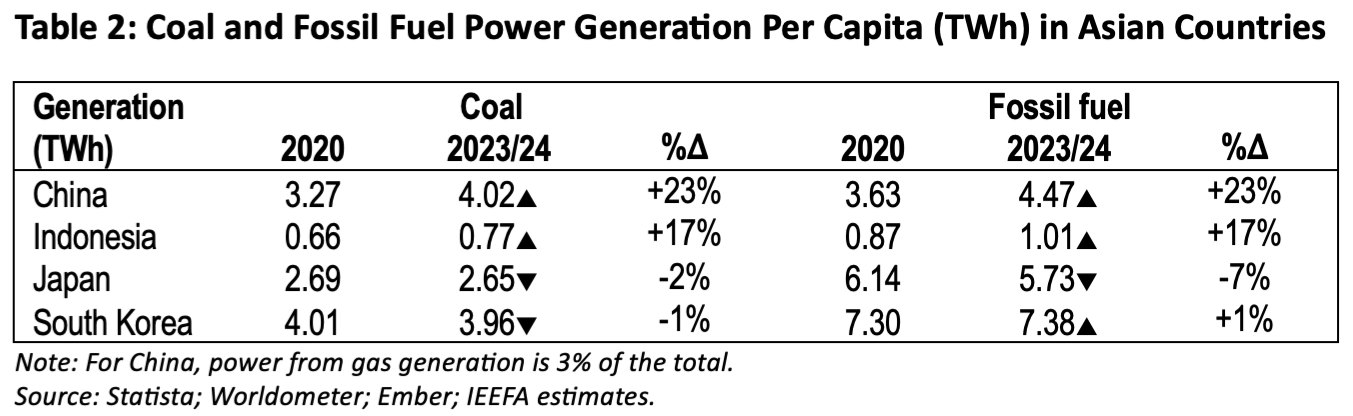

In 2023, Japan and South Korea had a higher share of gas-fired capacity in total fossil fuel generation at 54% and 46%, respectively, compared to 24% for Indonesia and 10% for China (Table 2).

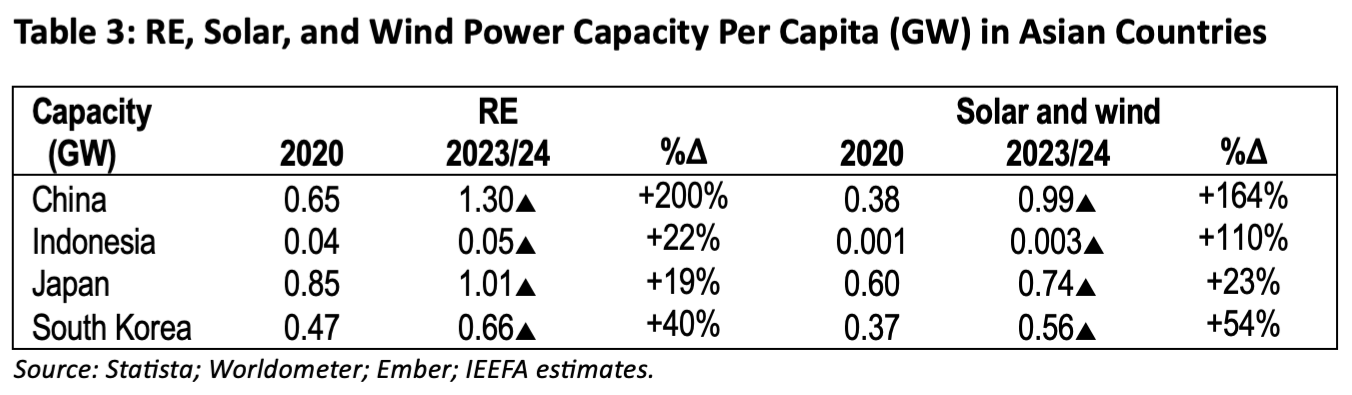

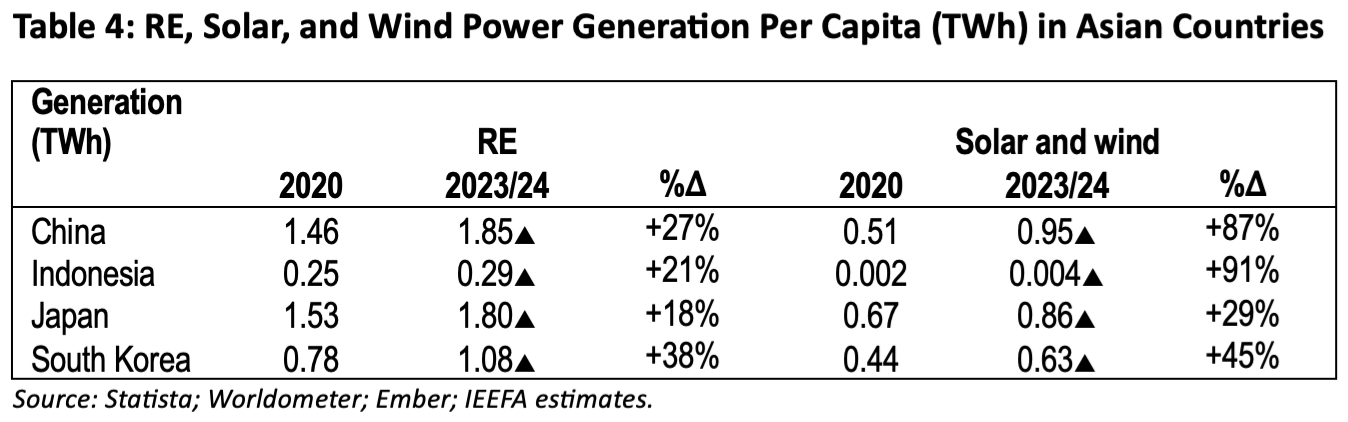

Meanwhile, all four countries have increased the share of energy sourced from renewables. China had the highest rise in absolute terms, with a 0.65GW increase per capita from 2020 to 2024, almost entirely driven by solar and wind (0.61GW). Japan added 0.14GW per capita of mainly solar energy from 2020 to 2023.

From 2020 to 2023, China recorded the largest increase in RE generation per capita, rising to 0.39GW. Japan and South Korea registered increases of 0.27GW and 0.3GW, respectively. China’s RE generation per capita was 46% of its fossil fuel generation, while Japan’s was higher at 69%. Indonesia had a minimal increase, which aligns with its limited increase in RE capacity.

Coal usage in the four countries

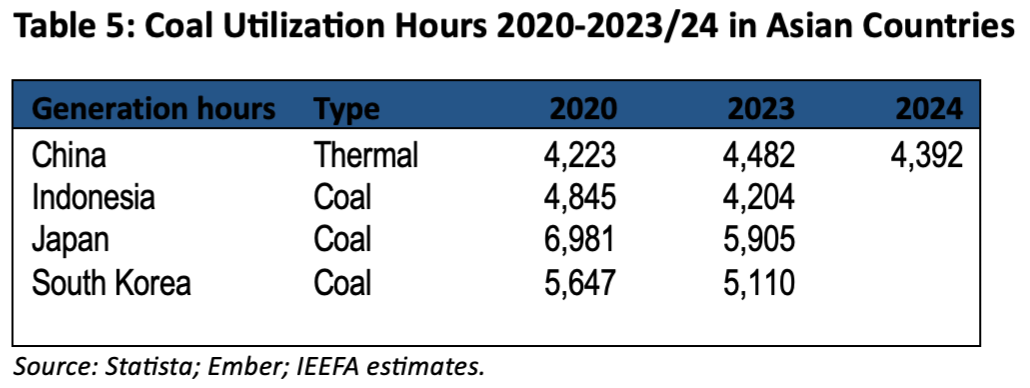

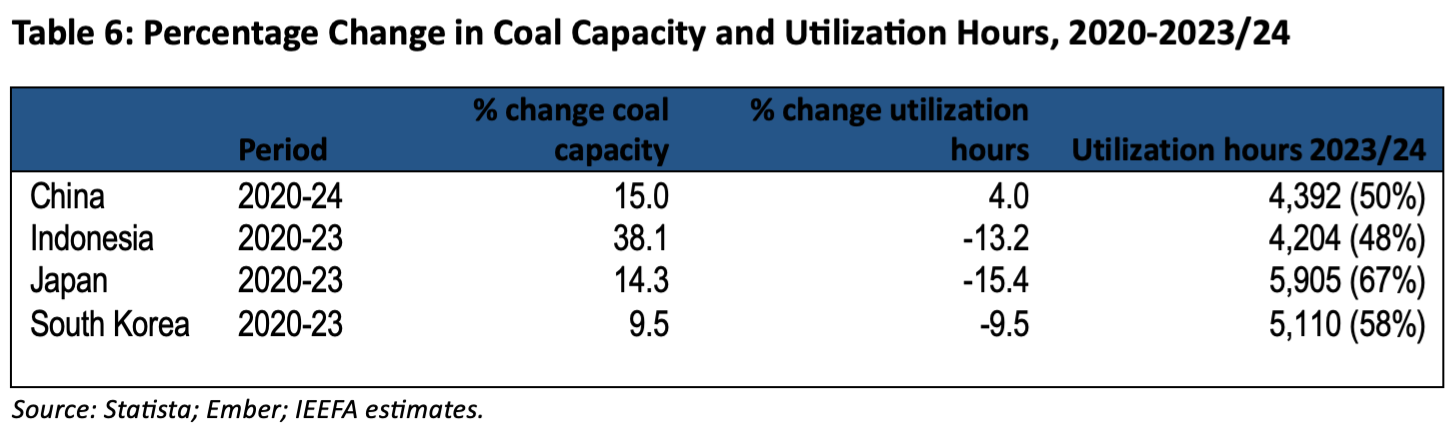

In 2024, China reported 4,392 utilization hours for its coal plants – an increase of 4% from 2020. This implies a 48% utilization rate of coal-fired power plants (CFPPs) for 8,760 total annual hours. In 2023, Indonesia’s utilization hours were 4,204, a decrease of 13% from the previous year, with a 38% increase in coal power capacity. For the same year, Japan’s coal utilization hours declined by 15% to 5,905, presenting a utilization rate of 67%. Meanwhile, in 2024, South Korea’s utilization hours were 5,110, a decrease of 10% from 2020, signifying a 58% utilization rate.

Compared with 2020, Japan and South Korea reduced their coal utilization hours in 2023 by 15% and 10%, respectively. However, both countries boosted their coal power capacity over the same period. Japan added 14%, and South Korea added 9% more coal capacity. Two units of 650MW capacity each were completed at Japan’s Yokosuka plant in June and December 2023.

These utilization rates are low for all four countries. Ultra-supercritical (USC) coal plants, used for the most recent builds, should have utilization rates of above 80%, while older subcritical plants should be able to operate at 65% and above. Low utilization rates imply that these countries may have overbuilt coal capacity. Thus, there could be substantial room to retire the oldest, least efficient plants. As RE additions progress, these rate dynamics are likely to evolve further.

RE eroding the share of coal generation in China’s power mix

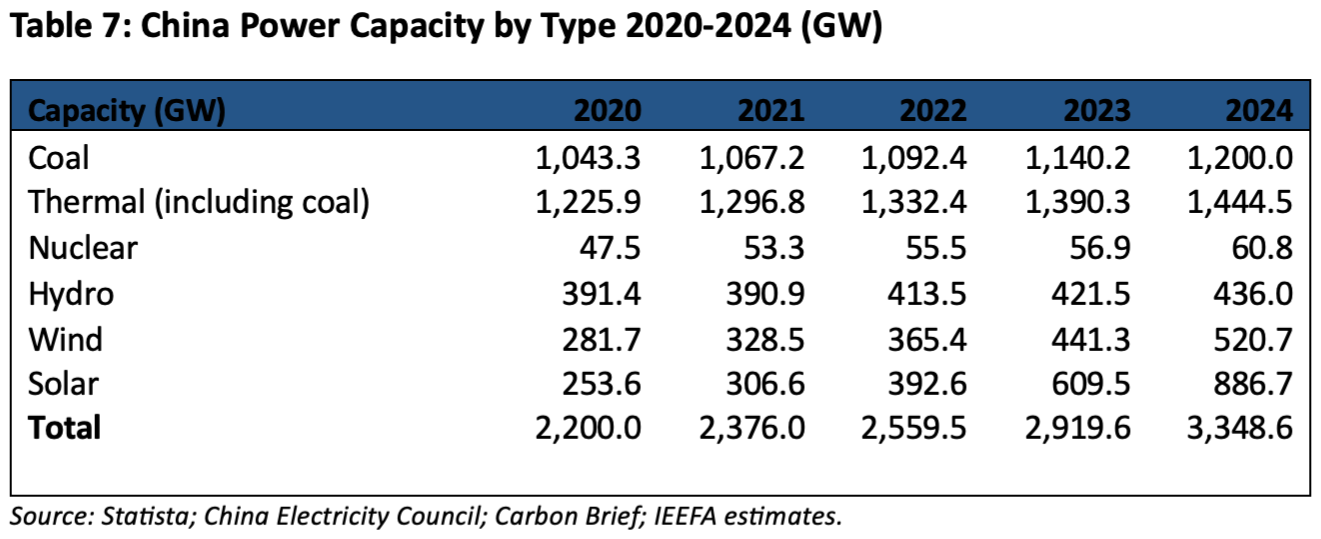

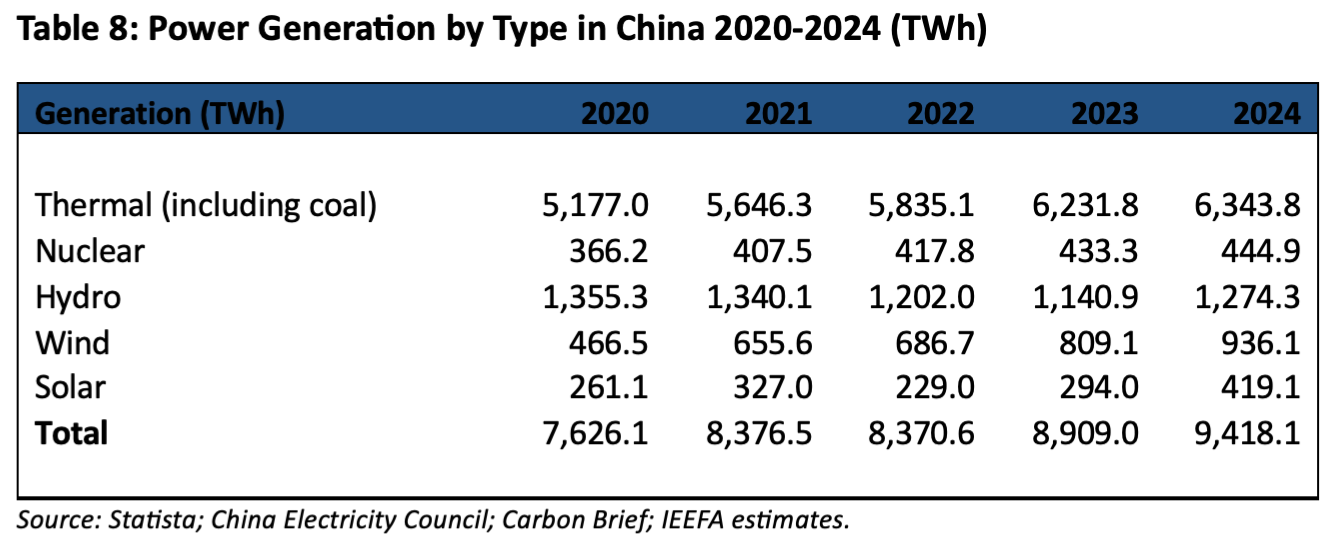

Since 2020, China has added enough wind and solar capacity to have the flexibility to reduce fossil fuel reliance. Wind and solar account for 42% of total power capacity in 2024 (Table 7), and RE accounts for 35% of electricity generation.

Recent events, such as the withdrawal of the U.S. from the Paris Agreement in January 2025, have directed the focus to China. Some commentators have presented China as a climate leader and emphasized the buildout of its RE capacity, while others stress that the country is still increasing its coal capacity.

The building of both RE and coal power capacity could be viewed as complementary. Currently, RE capacity is underutilized due to transmission constraints resulting in an urgency to upgrade the grid. The Lantau Group, a consultancy specializing in the China power sector, has stated that the country’s coal generation hours could peak during 2025. However, this is dependent on the availability of hydropower which in 2022 accounted for just 14% of power generation compared to 18% in 2020. Additionally, some of China’s new coal capacity additions are flexible USC coal plants, able to operate at rates as low as 30% utilization, giving priority to RE.

Global Energy Monitor’s Sustainability by Numbers states, “China is building more coal plants but might burn less coal”. In 2023, China added 50GW of coal but retired 4GW. Also, these coal plants are more likely to be approved at the provincial rather than the central level as this improves the economic scorecard for provinces. These conflicting decision-making priorities between central-based renewable capacity and provincial-based coal capacity have yet to be resolved.

There are two positive developments. First, the rapid buildout of solar and wind capacity from 2020 to 2024 provides the flexibility to use additional RE. Second, the current tariff pricing discourages growth in gas generation compared to competitively priced RE.

In 2020, China’s wind power generation capacity was 329GW, while solar power was 307GW. By the end of 2024, wind power capacity had increased by 85% to 521GW, and solar capacity had risen by more than twofold to 887GW. During this period, coal capacity grew by 15%, or 157GW, and total thermal capacity was 219GW, or 18%, compared to an 872GW increase in wind and solar power.

There are concerns that wind and solar power additions will slow in 2025. S&P Global reports that the National Energy Administration (NEA) has targeted 60% of non-fossil fuel capacity additions in 2025. 430GW of capacity additions are expected, and RE additions are estimated to be around 200GW. This is comparable with 275GW in solar and 88GW in wind power generation in 2024. Reuters reports that the China Photovoltaic Industry Association has forecast a range of 215GW to 255GW with the power pricing mechanism in June 2025 for new RE plants to sell power on a market basis. This new pricing could mean less generous subsidies for new solar farms. Carbon Brief reports that China started work on 94.5GW of coal power in 2024.

Wind and solar power accounted for 9.5% of total power generation in 2020, increasing to 14.4% in 2024. The estimated utilization hours for solar capacity in 2024 were 473 compared to 1,030 hours in 2020. This suggests that there is room to increase solar power generation subject to transmission grid upgrades. The State Grid of China has estimated capital expenditure at RMB650 billion (bn) or USD89bn for 2025.

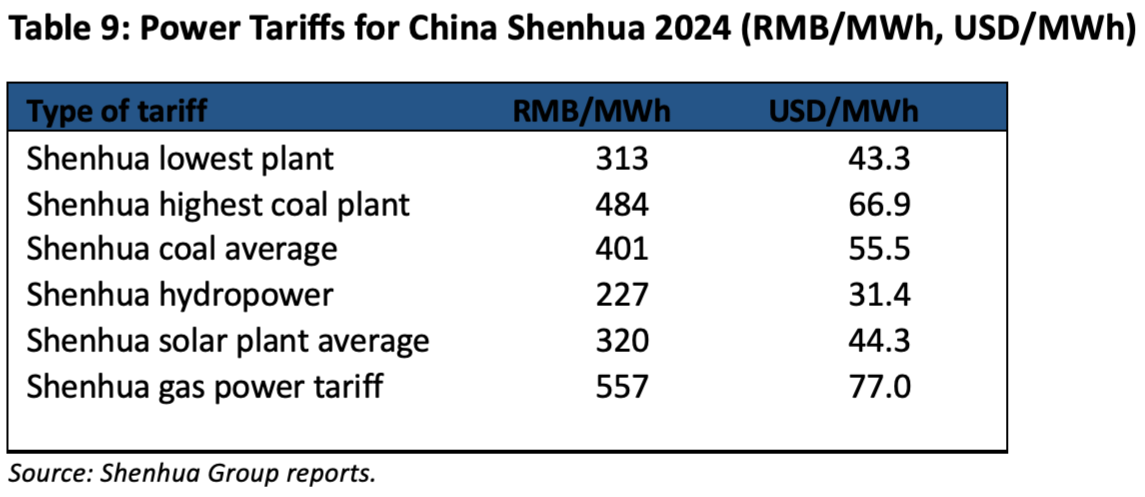

Tariffs are a significant reason for the increase in RE generation and the limited growth of gas power. The Shenhua Group’s (one of China’s largest utilities) 2024 annual report shows that the average coal tariff that year was USD55 per megawatt-hour (MWh) compared to USD44 per MWh for solar. The gas tariff was USD77 per MWh, which is 39% higher than coal and 74% higher than solar (Table 9). High gas tariffs are the primary reason that LNG is unable to displace coal in China’s power mix.

Despite rising Chinese imports over the last decade, LNG has not displaced coal and has been used for industrial purposes. RE has eroded the share of coal generation in the country’s power mix. China relies on domestically produced resources, not LNG, for energy security and reliability.

Starting from June 2025, China will move towards a market-based tariff for RE, resulting in higher tariffs and limited utilization for new projects. Existing RE projects will retain their current pricing, while new projects will shift to the new market-based rates. This could mean a surge in RE projects being completed ahead of the 2025 price changes.

Captive coal and RE transition challenges in Indonesia

Coal accounted for 56% of Indonesia’s 93GW power capacity in 2023, while gas constituted 22%. The country is emerging as the world’s top nickel supplier, used in steel and EV battery production.

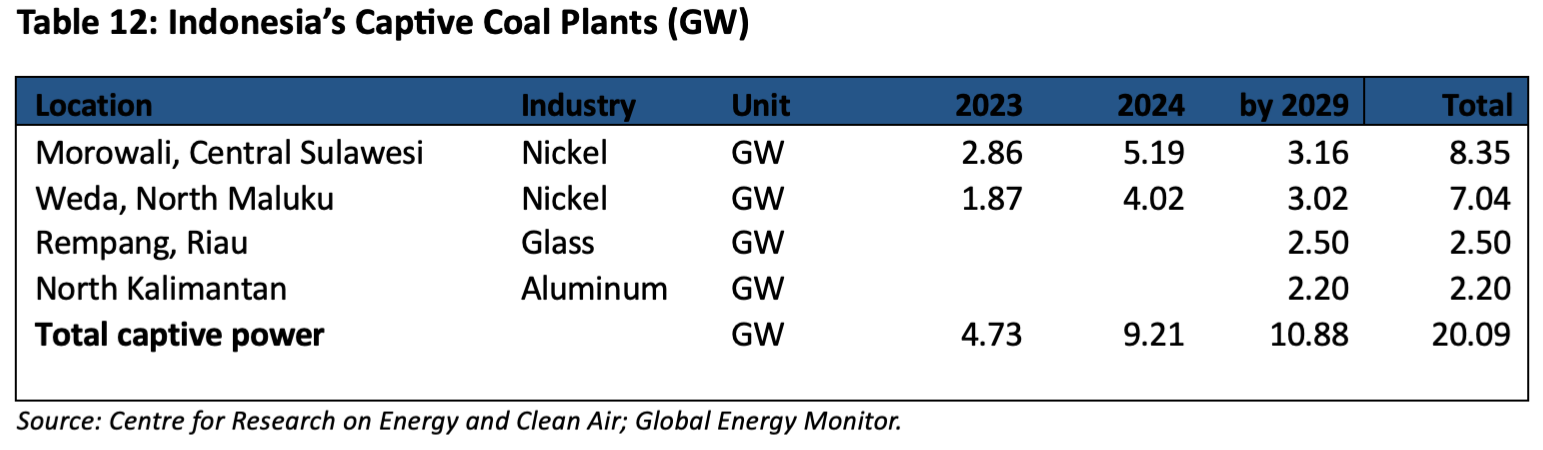

11.2GW, or 20% of Indonesia’s total coal-fired power generation capacity, is used to support nickel smelters. There are approximately 20GW of new captive coal plants in the pipeline. Any attempt to build out RE to replace coal power plants faces regulatory difficulties, including procurement and tariff mechanism challenges.

Indonesia faces three challenges in its transition to RE. First is the issue of captive coal plants. Ember estimates that out of the current 49.7GW of CFPP capacity, 11.2GW is from captive coal plants, mainly supporting nickel smelters, with an additional 20GW of captive coal-fired capacity proposed. The second issue is finding ways to mobilize the USD20bn from the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). While the U.S. has withdrawn from the program, Germany and Japan are stepping into co-leadership roles. The third issue is that RE projects face policy risks such as granting equity stakes to the national electricity utility, PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN), procurement transparency, carbon credits surrendering, and low RE tariffs.

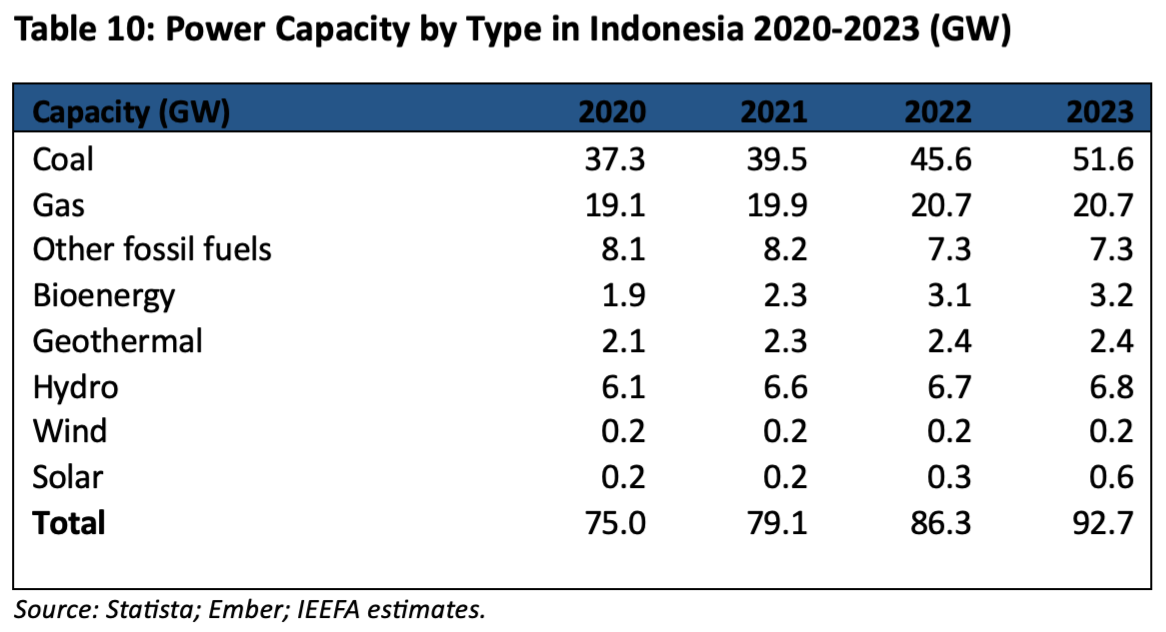

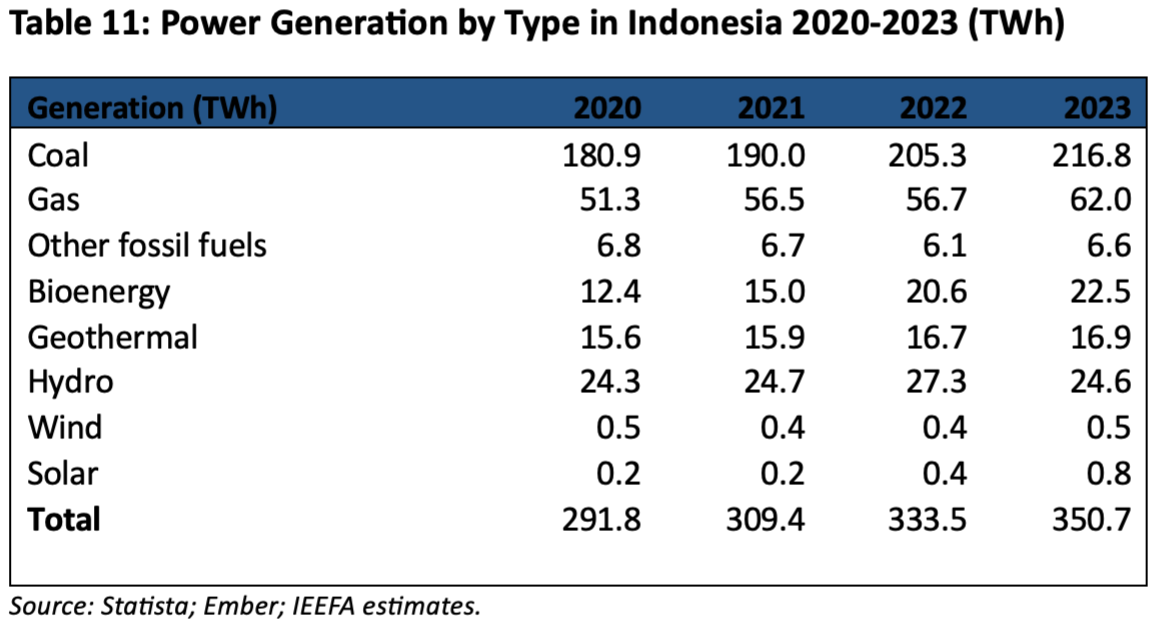

Indonesia’s coal capacity increased by 14.3GW from 37.3GW in 2020 to 51.6GW in 2023. Ember notes that 26.8GW of new coal capacity could be added by 2031, and captive coal capacity could reach 31.5GW. Over the same period, gas power capacity increased from 1.6GW to 20.7GW. Total RE (hydro, bio, geothermal, wind, and solar) rose from 10.5GW to 13.1GW, while solar power increased by only 0.4GW, with a negligible increase in wind capacity. The share of RE only accounts for 14% of Indonesia’s total power capacity in 2023, compared to 56% for coal and 22% for gas.

Overcoming hurdles to reduce coal-fired capacity and boost RE in Indonesia

The demand for electric vehicle (EV) batteries has driven Indonesia’s nickel output growth. According to industry consultant Roskill, nickel demand for batteries is forecast to rise from 6% in 2020 to 33% in 2030. Indonesia imposed an export ban on nickel ore in January 2014 and encouraged the building of new smelters for processing.

According to Statista, Indonesian nickel production was 770,000 tonnes in 2020, but by 2024, S&P Global calculates that production reached 2.1 million (mn) tonnes. Indonesia’s global nickel share has grown from 16% in 2019 to 43% in 2024. China-led investment made this increase possible. According to China’s Ministry of Commerce, the country’s total direct investment in Indonesia was USD4.4bn in 2021, and USD4.5bn in 2022. Chinese investment in the Indonesian nickel sector is estimated to be USD30bn, and there are currently 43 nickel smelters operating in Indonesia. These plants are powered by 11.2GW of captive coal power.

Private companies would be responsible for replacing these plants with RE projects. However, if RE plants have excess capacity to replace captive coal, that would need to be discussed with PLN.

The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air and the Global Energy Monitor highlight that other industries, such as glass and aluminum, may also require captive coal plants, identifying that an additional 15.2GW could be added by 2026.

The JETP incorporates ambitious national plans designed to support select developing economies, providing the financing to retire high carbon-emitting power plants and developing RE generation. There are currently four countries covered by the JETP - South Africa, Senegal, Indonesia, and Vietnam. The latter two are valued at USD20bn and USD15bn, respectively. The funding consists of grants, guarantees, and concessional and commercial loans and includes public financing from countries and regions such as the EU, United Kingdom, Japan, and Germany. Private funders include multilateral development banks and climate investment funds. Given current U.S. efforts to boost LNG exports, its exit from JETP may increase the scaling up of RE capacity without using gas as a transition fuel.

Indonesia has not included private captive coal power in its decarbonization commitments under JETP. This risks the program’s funding and support, given that supporting countries, businesses, and philanthropies are unlikely to assist in shuttering older coal plants in one area only to see new ones built elsewhere.

Current Indonesian policies and onerous bidding and contractual requirements that deter solar and wind power are the most significant challenges in replacing coal power in the long term. These raise costs and discourage private investment. In 2023, Indonesia attracted only USD1.5bn in RE investment but needs to secure USD146bn in the near term to meet the country’s 2030 climate target.

Several regulatory challenges are holding back renewable energy development in the country. First, either PLN or its subsidiary has to own at least 51% equity interest in RE projects. Second, ceiling tariffs for RE projects are too low, making achieving profit targets difficult. Third, under recent power purchase agreements, any carbon credits must be fully allocated to PLN, and independent power producers cannot benefit from them. Finally, the procurement procedures are not transparent. Revising RE project regulations can create an investor-friendly environment for Indonesia and accelerate the energy transition.

South Korea and its LNG “power tariff trilemma”

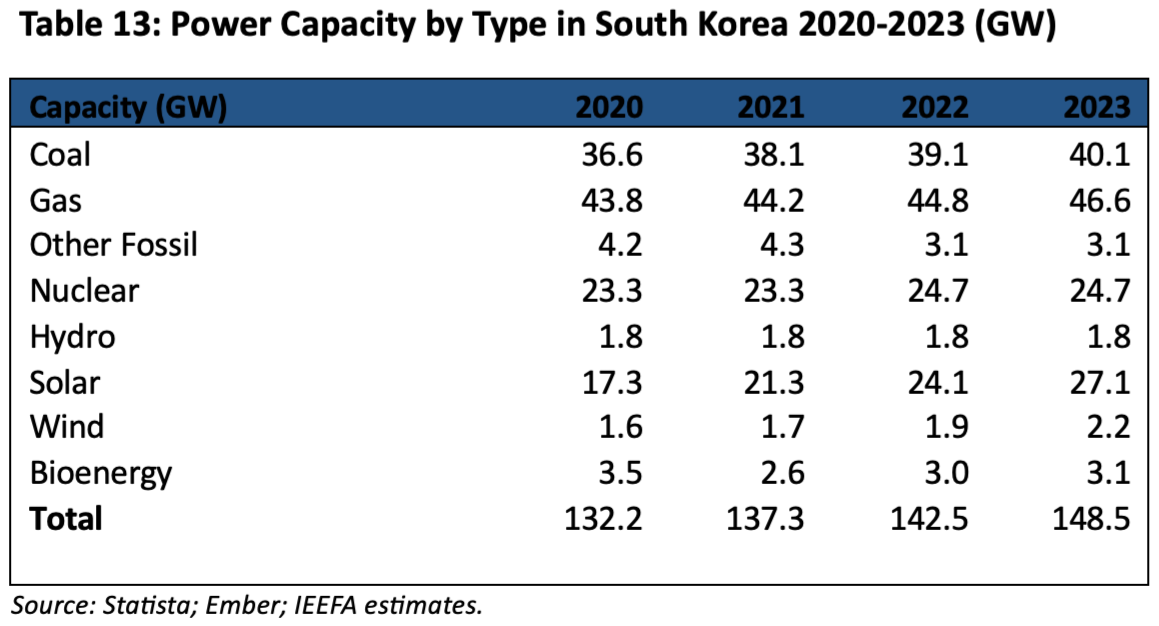

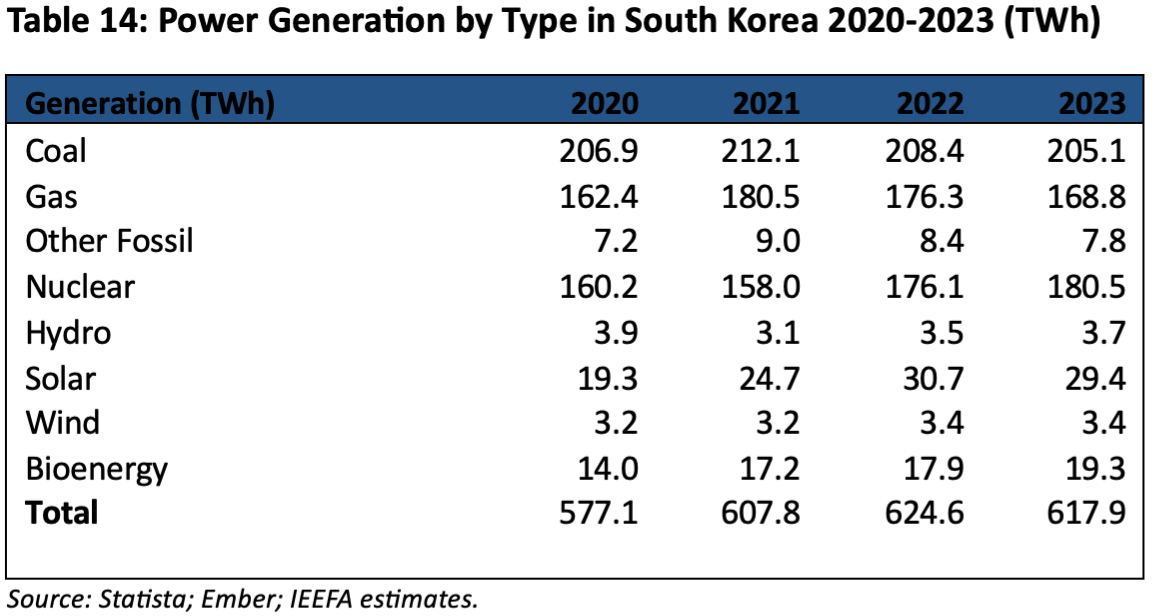

In 2023, coal accounted for 33%, and gas comprised 27% of South Korea’s power capacity. Due to increased solar power, RE (solar, wind, and bioenergy, excluding pumped hydro) constituted 23% of total capacity. The country is in a “power tariff trilemma” where interconnected challenges of energy security, competitiveness, and sustainability have contributed to rising electricity bills due to the high share of LNG-based gas power generation.

The country has also pushed to build new LNG import terminals and storage facilities despite having some of the lowest utilization rates for its existing terminals.

The country’s coal capacity accounted for 28% of the total power capacity in 2020 and 27% in 2023, while LNG constituted 33% of capacity share in 2020 and 31% in 2023. RE (solar, wind, and bioenergy, excluding pumped hydro) increased from 18% in 2020 to 23% in 2023, driven by a 10GW increase in solar power. This is half of China’s 36% wind and solar share of total capacity in 2023.

The share of coal in power generation declined from 36% in 2020 to 33% in 2023. The share of gas also dropped slightly from 28% in 2020 to 27% in 2023. In 2022, South Korea incurred USD17bn additional costs for LNG-fired power generation due to the over-reliance of utilities on fossil fuels. The slow adoption of RE is a missed opportunity to reduce power prices. The share of wind and solar in South Korea’s power generation increased from 7% in 2020 to just 9% in 2023.

South Korea pursued fossil fuel-oriented energy security, assuming it would guarantee an affordable electricity supply. This approach faced headwinds as the Russia-Ukraine war disrupted gas and coal markets. Soaring fossil fuel prices, especially LNG, and South Korea’s heavy reliance on fossil fuels (58.5% in 2023) led to total fuel costs of USD25bn during this period.

Due to South Korea’s regulated power pricing mechanism, the national utility Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) sold electricity to consumers at prices that did not cover fuel costs. KEPCO had to issue more debt to cover the revenue gap. At the time, the utility’s RE capacity was only 2% of total power capacity.

South Korea could benefit by reducing reliance on fossil fuels in the power mix and expediting the transition to clean energy sources. Power pricing should also be reformed to reflect actual costs.

Japan could benefit from reducing its reliance on gas

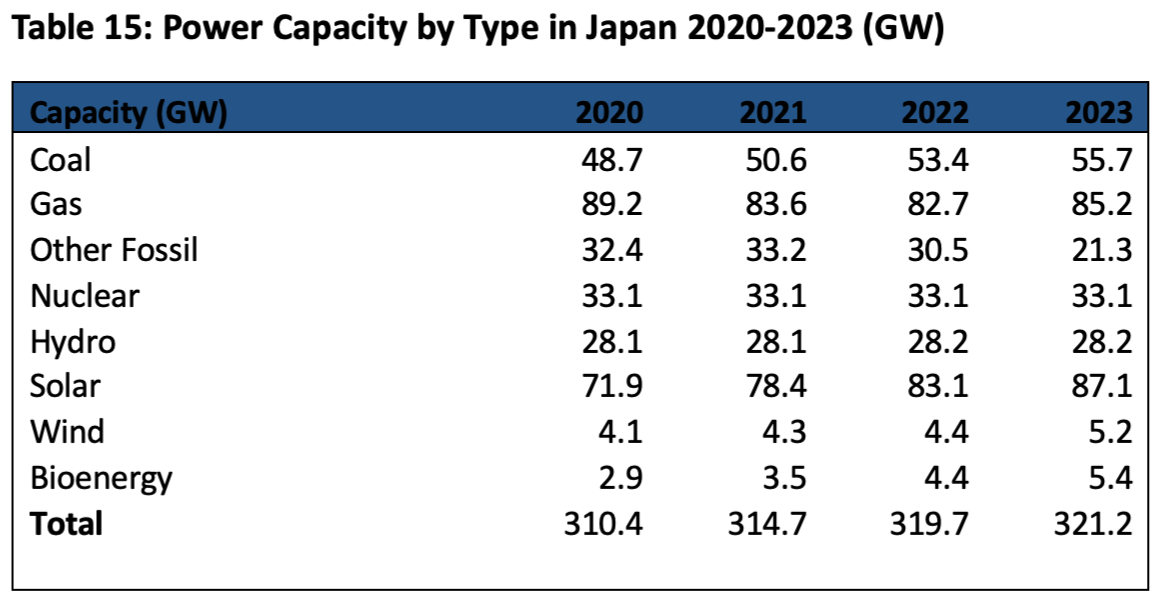

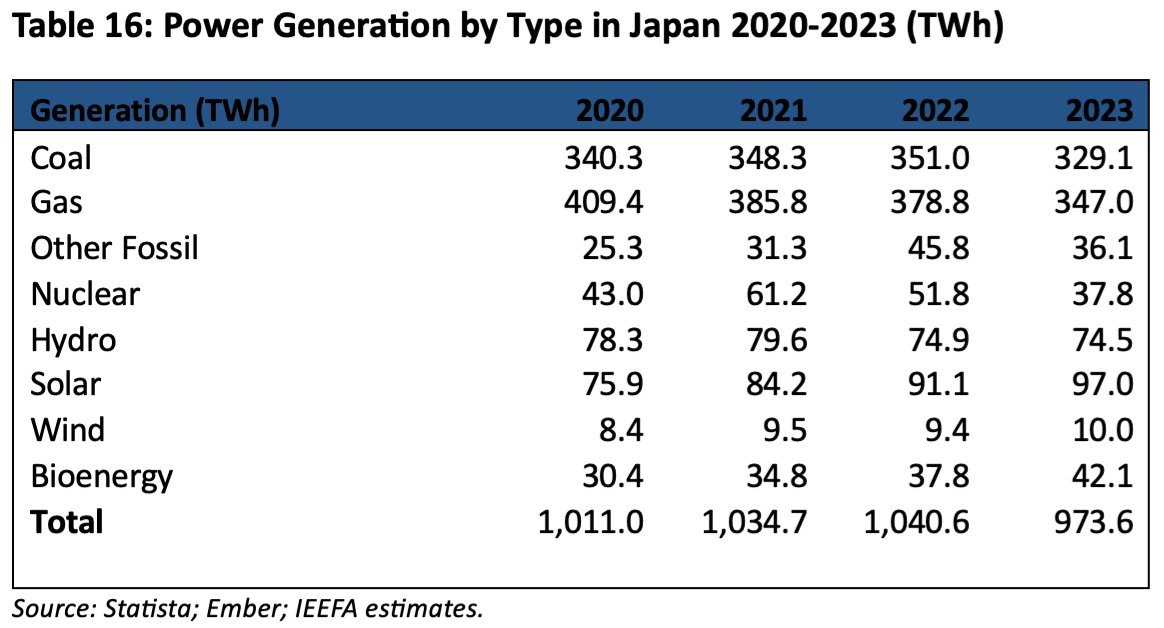

In 2023, coal accounted for 34% of Japan’s generation, while gas contributed 36%. RE sources (hydro, solar, wind, and bioenergy) constituted 23% in 2023 due to increased solar power.

Japan has the third-highest installed solar capacity globally due in large part to attractive feed-in-tariff policies instituted in 2012 in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima disaster.

The country’s LNG consumption has fallen 25% in the last decade as nuclear facilities have restarted and RE sources have developed.

Japan’s Seventh Strategic Energy Plan emphasizes a “self-development ratio”, encouraging Japanese companies to invest directly in fossil fuel development abroad. Shifting from fossil fuels to RE would reduce the risks of continued reliance on fossil fuels. Although the country has increased solar capacity from 2020 to 2023, the shares for coal and gas remain at a combined 44% for 2023. The share of RE (including hydro, solar, wind, and bioenergy) in the total capacity rose from 35% in 2020 to 39% in 2023.

The share of coal in power generation has remained steady at 34% from 2020 to 2023. Gas share in power generation declined from 41% in 2020 to 36% in 2023. In 2022, surging LNG prices and a weakened Yen drove Japan’s annual electricity price to JPY20.4 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) (USD0.14/kWh) compared to the 2005-2024 range of JPY6.5-16.5/kWh (USD0.04-0.11/kWh).

Japan aims to increase vertical integration in fossil fuel procurement and delivery and the self-development ratio from 35% to 50% by 2030. This ratio represents the share of the offtake amount of oil and natural gas controlled by Japanese entities. Notably, LNG projects in Mozambique, Canada, and the Middle East resulted in losses for Japanese companies.

RE development could help enhance energy security and affordability in Japan. The utility-scale sales rate for RE was JPY9.9/kWh in 2023, less than half of JPY22.3/kWh for gas and JPY18.6/kWh for coal in the same year. Japan, with its technological leadership, is well-positioned to integrate RE and grid-scale battery storage.

The economics of RE prevails despite unique challenges

From 2020 to 2023, all four Asian countries reduced coal and fossil fuel use and increased RE capacity. Despite renewables being the most cost-effective energy source, these countries are finding it difficult to break coal’s grasp. Japan and South Korea appear reluctant to write off the sunk cost of coal, while China and Indonesia are reticent to let go of a domestic but expensive energy source.

Despite each country’s unique challenges, expediting the transition to clean energy sources connects logically with economic and climate commitments. For Japan, South Korea, and Indonesia, where fuel costs are denominated in U.S. Dollars, accelerated RE deployment can create a natural near-term hedge against global volatility. China has already committed to a green technology future, becoming the world’s RE powerhouse.

Coal is on its last gasp – only legacy energy sector policy stands in the way of a self-reliant, self-sustaining future.

This article was first published in The Diplomat.