Japan's bet on hydrogen is still unwavering despite decades of lackluster progress

Key Findings

Japan's fixation on hydrogen needs to be contextualized within the backdrop of the island nation's industry influences, and their bet that many coal and gas power plants will persist and bring promise for hydrogen use.

It is questionable whether Japan will compete head-on with China on low-cost electrolyzers and renewables, there is a perceivable emphasis on midstream value chain and end-use technologies instead.

Japan's hydrogen plan aims for but does not guarantee clean hydrogen. A close public watch is needed to ensure decarbonization goals can be met credibly with a clear timeline.

Industrial countries in Asia, such as Japan and South Korea, have their own ways of pursuing energy transition that cater to their circumstances. Power supply chains with neighboring states and domestic energy resources are not luxuries available to every country, so other developed nations should look at individual cases judiciously.

Such is the general narrative in response to criticism of how Japan and South Korea have gone about reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

Indeed, both countries face specific challenges, being the fifth and eighth largest energy consumers globally while depending primarily on imported fuel. In 2020, Japan had an energy self-sufficiency ratio of 11% and South Korea, 19%, both supported by domestic nuclear power and, to a lesser extent, renewables.

This is where hydrogen has entered the picture, along with ammonia and other associated products (collectively referred to as “hydrogen” in this commentary). As newer market entrants, these fuels are without a doubt subject to heavy influence from major domestic industries.

Of the two countries, Japan has made more pronounced plans and has naturally raised more eyebrows over its fixation with hydrogen, from hydrogen-powered homes and fuel-cell vehicles (FCVs) to the cofiring of ammonia in coal power plants. Several institutions have suggested that, rather than lean on these unproven technologies, Japan would find it most effective to decarbonize through tried and tested means such as wind, battery-based electric vehicles and grid storage.

To be fair, Japan had the third largest solar power generation in the world in 2021, while South Korea was 10th. Wind power generation in both countries is modest. Renewables pursuits are ongoing, with an obvious affinity for hydrogen.

A look at the past to understand the present

Japan’s interest in hydrogen dates back to well before its 2017 Basic Hydrogen Strategy. Starting in the 1970s, plans have largely centered on hydrogen-powered fuel-cell technology and energy generation, leading to the development of FCVs since the 1990s.

FCVs appeal to Japan because the country is home to some of the largest automakers – an industry that is the leading consumer of oil. It follows that displacing oil consumption, an expensive primary energy source, is a long-standing key objective of the world’s fifth largest oil importer. There is good alignment between energy security and industry aims, and hydrogen, throughout those decades of development, held the promise of becoming a key part of the future.

The mobility sector has always featured prominently in Japan’s hydrogen strategies. About half of the national hydrogen budget support from key ministries in recent years has been spent on FCVs and hydrogen stations.

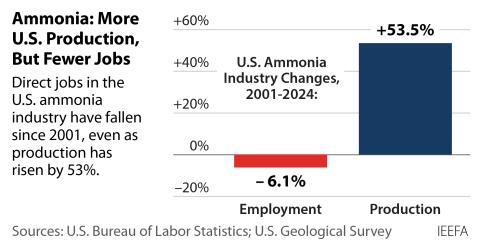

Hydrogen, unfortunately did not really take off as a fuel, confined mainly to oil refineries and the fertilizer industry instead. The storyline changed with the 2015 Paris Agreement and rising global attention on emissions when hydrogen slowly resurfaced on the world stage trailing behind renewables.

GX, a new initiative in Japan’s green transformation, sets out significant targets and funding for renewables, but the presence of hydrogen is still strong.

In May, the Hydrogen Council said more than 1,000 projects had been announced globally, although only 9% had reached the point of final investment decision. Projects in Europe and the United States had been flooded with government incentives.

Would Japan risk competing head-on in hydrogen with China?

For all the hype, hydrogen remains the same molecules. The challenges of the past prevail, from energy inefficiency losses to costs and transport problems.

Japan’s hydrogen strategy outlines clear targets for reducing costs, which are largely a function of technology and resources.

Blue hydrogen, produced from fossil fuels with carbon capture, will likely remain under scrutiny given the underwhelming performance of carbon capture technology and the potential for methane leakage. Nonetheless, with the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Group claiming a 70% global market share in carbon capture, Japan will probably continue pursuing the blue hydrogen path, thus warranting a close watch on its emissions trail.

In the green hydrogen space, which relies on low-cost clean electricity and technology, Japan is far behind China in keeping expenses down. BloombergNEF reported a levelized cost of green hydrogen in Japan of two to more than three times that of China. Costs are expected to converge in the next few decades but under limited renewables uptake in Japan, renewable electricity will likely come at a premium, making it difficult to reconcile with the need for low-cost clean electricity.

The challenge escalates with the significant cost advantage of Chinese electrolyzers, which portends strong competition in the global market for technological dominance. It is quite possible that the Japanese may become more selective in their hydrogen focus areas, especially considering their updated strategy aims to increase attention to overseas markets.

The emphasis is quite apparent on at least two fronts: midstream maritime transport and end-use technologies. Recent years have seen the world’s first liquefied hydrogen shipment from Australia on a vessel built by Kawasaki Heavy Industries; the first blue ammonia cargo from Saudi Arabia; and the first liquid organic hydrogen carrier shipment from Brunei – all ending up in Japan. For the Japanese, sea transport is a serious endeavor given their limited import channel options.

On end-use technologies beyond the mobility sector, Mitsui & Co in June concluded an ammonia supply contract to support 20% cofiring trials at JERA Hekinan power station, among the world’s largest coal-based stations. JERA has also finished modifying the gas turbine in a U.S. power plant to accommodate up to 40% of hydrogen cofiring, to name but a few Japanese industrial heavyweights jumping on the hydrogen bandwagon. These large companies are also responsive to emerging regulations in other jurisdictions, such as the European Union’s emission limit for labeling gas power plants.

Criticism varies. Coal plants running with ammonia cofiring would very likely have more carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions than conventional gas power plants. High costs would still be a concern in adopting ammonia and hydrogen firing, especially when transported by sea.

Brushing the skeptics aside, Japan is spending US$107 billion on hydrogen supply chains and aiming to have 1% hydrogen or ammonia in the power mix by 2030, indicating its commitment to go all out in pursuing hydrogen.

Clean hydrogen is not (yet) guaranteed

Since CO2 emissions from hydrogen production vary widely, concerns have been raised regarding Japan’s laissez-faire approach to hydrogen import trials, which mostly brings in hydrogen produced from emission-intensive processing of brown coal or gas.

This approach is seemingly aligned with the Japanese hydrogen strategy of focusing on development of end-use technologies and supply chain expansion, accompanied by efforts to decarbonize over time. Plans to align with global hydrogen emission standards are embedded in the strategy, but a close public watch is needed to ensure decarbonization goals can be met credibly with a clear timeline.

Hydrogen importers that sidestep these commitments risk offshoring their emissions and negating their decarbonization plans.

Spillover risk

Skepticism about over-reliance on hydrogen-based commodities will likely continue. Ultimately, however, each country has the right to design its own strategy in pursuit of climate goals.

Externally, the influence of hydrogen risks spilling over to Southeast Asia (SEA) and other neighboring regions.

Japan-led initiatives, such as the Asia Zero Emission Community, promote the use of hydrogen and carbon capture. Last year, a power-sector decarbonization report was issued for Indonesia with support from the Japan International Cooperation Agency. In its action plan, hydrogen/ammonia, biomass, liquefied natural gas, and carbon capture, use and storage were the top four items on the list.

Elsewhere, exploration of hydrogen production and uses such as cofiring has been noted in Malaysia and the Philippines. With SEA’s young coal fleet averaging 12 years old, Japan is seemingly confident that large numbers of coal and gas plants will remain operational in the foreseeable future, thus presenting opportunities for hydrogen to help them decarbonize.

Many emerging markets are at the juncture of shifting toward cleaner energy. For countries which struggle to pay a gas price of US$7 to US$9 per million British thermal units, placing a bet on an expensive and inefficient energy carrier remains questionable.

Japan knows well the limitations and challenges of hydrogen products. Experts have warned that given hydrogen’s inherent weaknesses, the country may be wading into a costly energy economy and risking its competitiveness in the process.

Nevertheless, the momentum of its domestic industries, whether in automobiles, thermal power generation or carbon capture remains strong.

Similar to other governments’ support for hydrogen, optimism can be sensed throughout the Japanese strategy. Yet a missing footnote is warranted, given hydrogen development does not happen in a vacuum. Other clean energy technologies are moving rapidly, posing strong competition.

On a more optimistic note, Japan looks like it knows it cannot afford to lose more battles for dominance of the future energy landscape. The country’s Green Innovation Fund, launched in recent years, allocated a budget for hydrogen and ammonia that was at least three times wind and solar power generation. Considerations that the latter’s room for innovation is narrower could have come into play, but it certainly shows where Japan is placing its bets.

This commentary was originally published in New Energy World