Japan and the G7 climate commitment: how will they follow through?

Key Findings

Japan’s G7 announcement supports meaningful and effective solutions to climate change. However, its institutional contradictions and challenges will need to be purposefully addressed.

For Japan to increase the chances of successful implementation of G7 policy and meet climate goals:

- Examine both the definitions and outdated underlying assumptions ADB and Japan use to allocate resources biased in favor of natural gas

- Focus financial and technical resource awards by ADB on the most catalytic and forward-looking energy projects

- Assure true alignment with the Paris Agreement’s fundamental outcome goals when determining program direction and financial offerings from JICA and JBIC

Japan’s decision to align with other G7 nations ending financing of fossil fuels in other countries sounded a clear note of unity amid the tangled, conflicting commitments that are the norm in the global climate debate. The unified effort needed to create effective climate change action will however test Japan’s leadership role as it works to navigate competing interests successfully.

The G7 is a forum for cooperation among seven of the world’s largest economies – Canada, the European Union, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In connection with the 2021 COP26 climate summit, several countries – including six of the G7 nations – signed a statement to end subsidies for fossil fuels. Finally, Japan agreed to join this alignment at the May meeting of G7 Energy and Climate Ministers.

Japan’s move reflects its recognition of climate urgency. Like most economic leaders amid the energy transition, Japan has made many ambitious policy pronouncements to decarbonize, both domestically and abroad, but struggles to put those words into action. A core challenge Japan faces is its domestic economic structure, tied to decades of heavy industrial investment, accounting for over 20% of GDP. Historically, Japan’s industrial giants have benefitted from the government’s infrastructure-heavy public investment paradigm, complemented by government support for Japanese equipment exports to neighboring markets.

Japan has credibility in meeting the energy transition challenge, built upon decades of pioneering technological leadership. However, now, particularly in renewable energy, Japan sees this leadership being challenged by China and Europe. The government and its industry scions have a difficult choice to make – attempt to compete with or complement competitors in renewable energy technologies or continue to rely on variations of fossil fuel themes to support the legacy industry.

Japan’s leadership derives partly from its powerful role as the largest shareholder of the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The ADB mobilizes over $35 billion annually to support regional development. Japan marries this position with the high-profile bilateral activities of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), and its export credit lending and guarantee arm, Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), effectively doubling ADB’s money. But how best to use those monies?

ADB’s new Energy Policy 2021 (EP21) surprised many observers by emphasizing the ongoing role of natural gas in climate policy. Seven months later, the G7 announcement contained a bold pronouncement to end investment in fossil fuels, but it also included a similar qualifier allowing for new natural gas infrastructure.

"...we commit to end new direct public support for the international unabated fossil fuel energy sector by the end of 2022, except in limited circumstances clearly defined by each country that are consistent with a 1.5 °C warming limit and the goals of the Paris Agreement."

The “limited circumstances” justifying natural gas financing stem from two interconnected factors: the existence of legacy economic structures and the perceived technological limitations of renewable energy. Together, these factors bolster the natural gas exception, a decision that will impair the rapid deployment of climate solutions that are, in most cases, financially and environmentally superior choices. The end result? Continued lock-in of fossil fuel costs and consumption beyond many countries’ net-zero target deadlines.

A fundamental flaw in the clever wording of the G7 and ADB statements is that they discount Japan’s catalytic role. The ADB and cooperative structures like the G7 are vehicles Japan can use to drive the sustainability revolution. Instead, for now, Japan appears to be protecting industries seeking to delay the transition, rather than leverage their vast capabilities to be a key part of it.

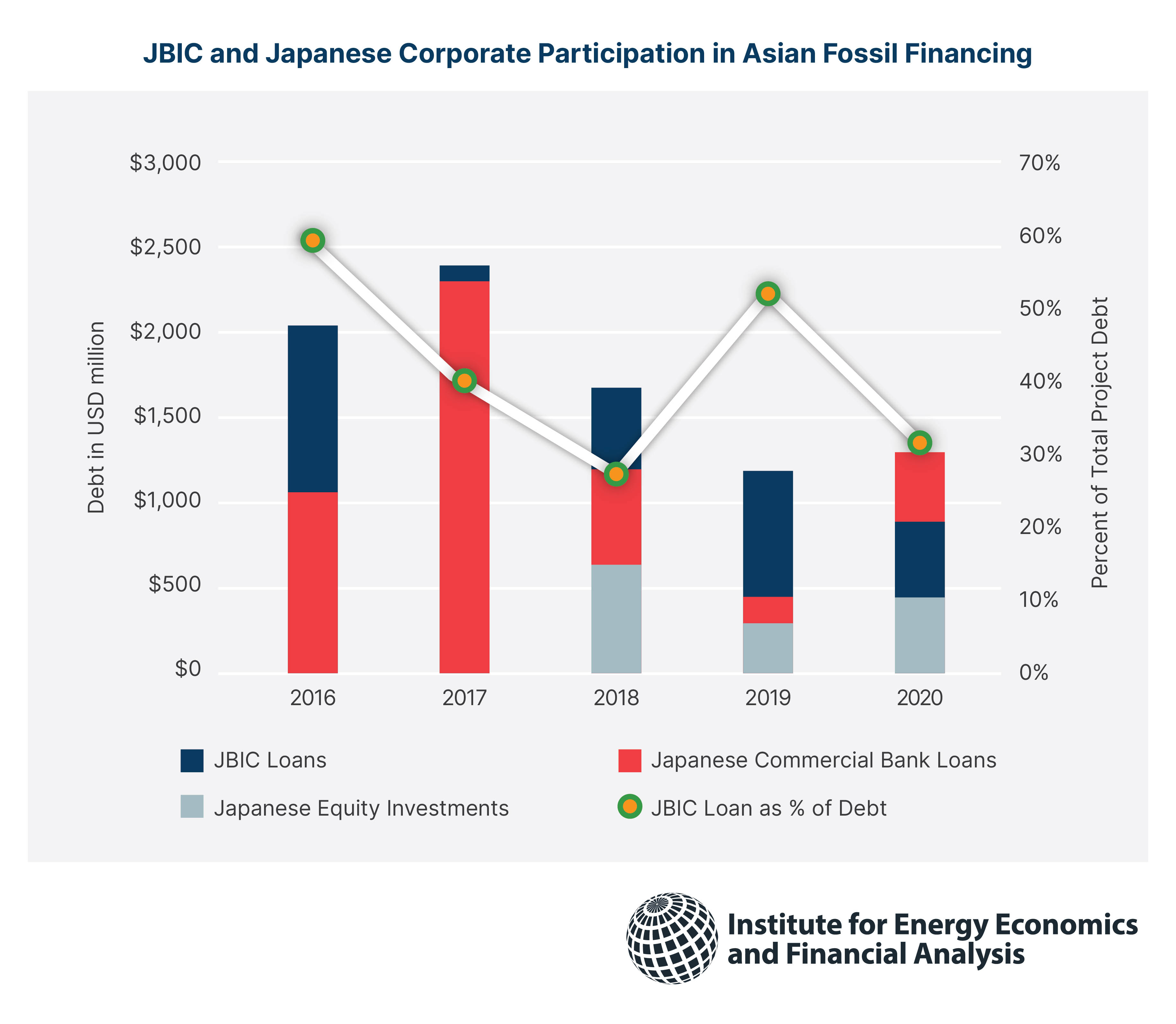

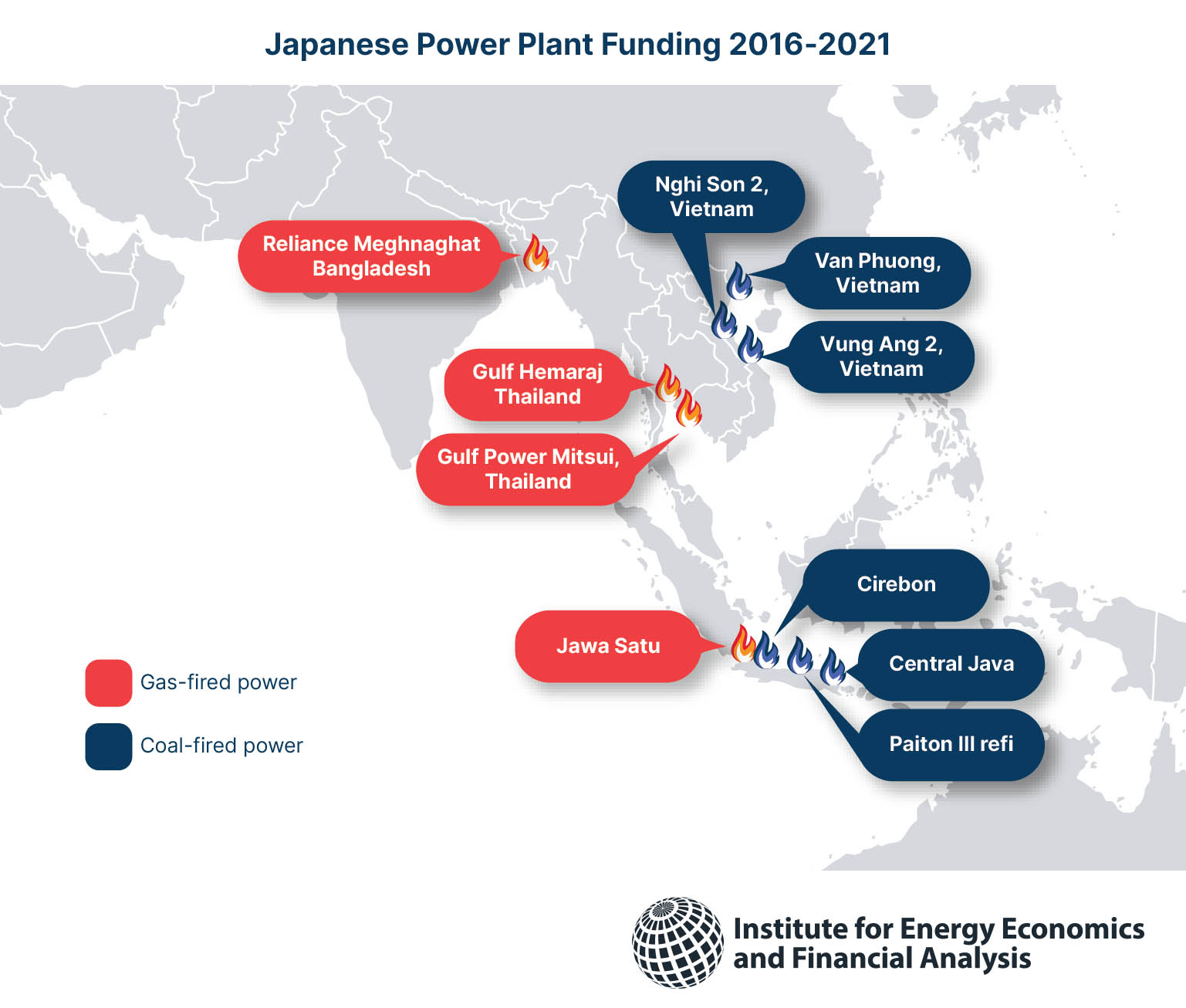

There is reason to be concerned. In the past five years, Japan has been on an Asian fossil fuel funding rampage. JBIC has provided over US$8.2 billion in direct lending to ten projects, escorting US$6.5 billion in Japanese commercial bank loans and US$1.5 billion in equity. This funding created 14.2 gigawatts (GW) of coal- and gas-fired power generation, with all projects featuring Japanese direct investment, equipment supply, or both. While this may be beneficial for those Japanese companies, the plants they helped create in third countries emit CO2 for the next 30-plus years.

Much of Japan’s fossil energy focus is done in the name of “economic development” and “advancing opportunities” for emerging markets. However, the extreme price volatility of the past two years in coal, oil, and LNG markets has shown that dependence on fossil fuel investments is neither cheap, reliable, nor sustainable. Japan knows the ramifications of this fossil-heavy reliance all too well. Thus, saddling developing economies with the same energy infrastructure burdens that industrialized economies struggle to escape is counterproductive.

Japan’s lack of an explicit alignment of purpose between domestic and global investment strategies undermines its leadership position. Policies should prioritize and maximize the development of alternative resources, over support for fossil fuels, including natural gas. It should seek to leverage the best technology and most cost-effective aspects of the new energy economy, without forcing countries to traverse expensive, ill-defined ‘transition’ waypoints among different fossil fuels.

To increase the chances of successful implementation of G7 policy and meet climate goals, Japan should focus attention on the following areas:

- Examining both the definitions and outdated underlying assumptions ADB and Japan use to allocate resources biased in favor of natural gas.

- Focusing financial and technical resource awards by ADB on the most catalytic and forward-looking energy projects.

- Assuring true alignment with the Paris Agreement’s fundamental outcome goals when determining program direction and financial offerings from JICA and JBIC.

Japan’s G7 announcement clearly supports meaningful and effective solutions to climate change. However, its institutional contradictions and challenges will need to be purposefully addressed if Japan is going realize the sustainability leadership role within its reach.