Indonesia’s green taxonomy walks a tightrope in balancing industries of the past and the future

In January 2022, President Joko Widodo of Indonesia launched the country’s first green taxonomy. This is a positive and potentially significant move to unlock green private capital to meet Indonesia’s commitments under the Paris Agreement.

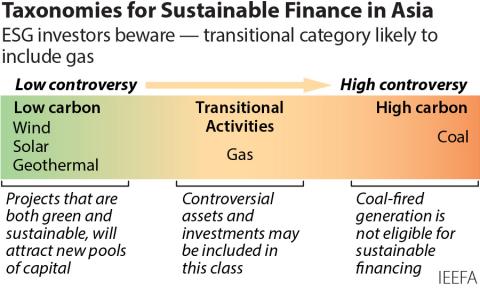

Unlike other taxonomies, Indonesia’s green taxonomy applies the traffic light system to represent the types of activities from a sustainability lens: green for activities that “protect or improve the environment”, yellow for activities “not significantly harmful to the environment”, and red for activities “harmful to the environment”.

The concept is interesting. Using road rules as interpretation, investments in Indonesia’s green activities could then be deemed as “proceed as is”, yellow as “prepare to stop”, and red as “stop immediately”.

However, anyone familiar with Indonesian traffic rules would know that, in practice, the meaning of the yellow light is subjective and varies in application. It can mean “accelerate (and slip through…)” or “slow down to a complete stop”. Frankly, it’s usually the former.

Which begs the question, what does the yellow tier in Indonesia’s green taxonomy mean as it relates to green and sustainable financing?

The controversial yellow tier

First off, the Indonesian government deserves applause for keeping its green tier for electricity generation activities truly green. It appears that only projects sourced from renewable energy are assigned the green label if the project receives Indonesia’s gold PROPER Award, a local company performance rating program for environmental management.

While it is unclear whether Indonesia’s gold PROPER award criteria align with international standards for green electricity generation activities, not recognising coal or gas-fired power as green, under any circumstance, is strategic.

The problem is with its yellow tier, particularly what this category of activities signals.

To qualify for this tier, the project must obtain the blue PROPER award and meet local environmental regulations set by relevant ministries. The greenhouse gas emissions criteria for this tier are not defined.

Based on IEEFA’s analysis, however, Indonesia’s unabated oil, gas and coal-fired power projects are likely to fall in the yellow tier. Most of these projects have a track record of receiving the gold PROPER award, a level higher than the blue PROPER award.

Even more concerning is that fossil fuel power projects that meet the yellow tier criteria can be regarded as ‘not significantly harmful to the environment’, which would be at odds with scientific evidence that burning coal, oil and gas are detrimental to the climate. The terminology could mislead the non-critical eye to conclude that the yellow tier contains a series of environmentally benign investment opportunities.

This also brings into question how financial markets will use the new taxonomy: do activities in the yellow tier qualify for green or sustainable financing?

Understandably, businesses predominantly operating in the yellow category—including fossil fuel power companies—need financial support to transition into environmentally sustainable businesses.

Therefore, it is acceptable to raise green or sustainable capital to transform such companies into credible, clean energy businesses, but not to advance fossil fuel power expansions or funding existing plants.

Until market discipline in implementing and enforcing Indonesia’s green taxonomy is evident, investors should pay special attention to the yellow tier, which is likely to carry high-emission, harmful and future stranded assets.

Indonesia’s place in the state of taxonomies

The lack of comparable emissions criteria puts Indonesia’s green taxonomy in stark contrast with its global peers, limiting its usefulness. In addition, most other taxonomies do not have an equivalent yellow tier.

China’s Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue, the country’s green taxonomy, outlines green activities only and their emission specifications, and excludes fossil fuel electricity generation.

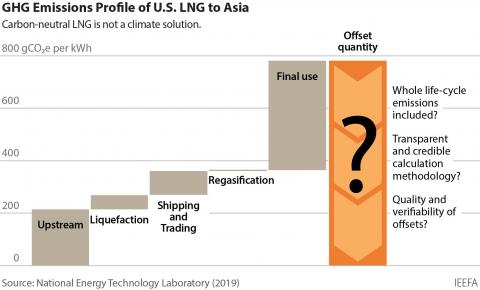

The EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance requires an emissions threshold of 100 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilowatt-hour to qualify for their green label. At this specification, coal-fired power projects do not qualify as green and gas-powered generation will likely require the use of carbon capture technology, which is yet to be proven economically or technically viable at scale anywhere in the world.

The taxonomy dichotomy risks Indonesia's credit standing

As the classification systems underlying Indonesia’s green taxonomy and its peers are notably different, foreign capital—specifically that with an environmental, social and governance focus—is likely to ignore Indonesia’s green taxonomy if the rules are more laxed than those of its home market(s), where these sources of funds are subject to scrutiny.

In October 2021, Moody’s reported that 31% of the country’s on-balance sheet loans are concentrated in industries with significant carbon transition risk, the third highest share among G20 countries.

Without a narrower interpretation of Indonesia’s yellow tier, local lenders and investors that do not share the level of examination in foreign markets are at risk of holding even more carbon-intensive and future stranded assets. This creates further domestic investor exposure to Indonesia’s climate-related risks, exacerbates the challenge of meeting their decarbonisation pledges, and hinders their longer-term financial resilience.

Will Indonesia’s three-tiered taxonomy promote clearer pathways to decarbonisation?

Indonesia’s progress towards meeting the Paris Agreement depends on how successful its policy measures are in mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Just as local road rules are interpreted and actioned according to an individual’s interests, so too can Indonesia’s green taxonomy if clearer financial regulation and effective enforcement are absent.

This, in turn, puts President Widodo in an awkward position as he leads the G20’s push for climate action.