India’s New Emissions Target Adds Momentum to Global Energy Transition

India last week became the last major economy to file a pollution-control plan in advance of the Paris Climate Conference in December, but one of the most important.

Its document carries huge global significance. And while it is a harbinger of things to come it is a measure, too, of which way the wind is blowing, so to speak.

In its formal Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), India is pursuing a fivefold increase in renewable energy by 2022, an increase of such magnitude that it will drive r drive technology, innovation and cost reduction not just in India, but worldwide.

India’s ambition is well-rooted in reality. The cost of installing solar energy has dropped by 70 percent in the past five years, and the beginning of an Indian renewable-energy investment stampede is evident, as we noted in a report we published a few weeks ago (“India’s Electricity Sector Transformation”) that documents the more than $100 billion committed to India’s renewable sector in 2015 alone.

In its INDC, India has committed to lift renewable energy installations from the current 36 gigawatts to 175 gigawatts by 2022 and to push new renewable energy installs to 40 percent of installed capacity by 2030, up from 13 percent today.

These goals are in line with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s push toward a rapid energy transition, and it’s not just a government phenomenon that’s occurring. A number of leading Indian firms have made significant new capital investment commitments to renewables—ReNew Power, Welspun Energy, NTPC, Reliance Power, Tata Power and Suzlon Energy have collectively announced tens of billion dollars of proposed investments in Indian solar and wind projects in recent months. Adani Enterprises has the world’s largest solar plant already under construction in Tamil Nadu, and Adani has announced it will invest a total of $16 billion in eight new solar projects across India.

Major global companies are also angling for a piece of the fast-growing renewable energy pie in India. These include Trina Solar, SunEdison, First Solar, ABB, Engie, Enel Green Power and China Light & Power—all of which are bringing global capital and technological expertise to the country. This is on top of the recent joint commitment by SoftBank, Foxconn and Bharti Enterprises to invest $20 billion over the next five years in Indian solar.

MOMENTUM IS BUILDING AS EACH DAY GOES BY, AND ONE RESULT WILL BE LESS RELIANCE ON COAL-FIRED GENERATION. India’s transformation turns on rapid diversification of its electricity grid,with emphasis, too, on expanding both hydro-electricity and nuclear in addition to renewables. Thermal generation capacity, as a result, will decline by our estimates to 55 percent of the total by 2030, relative to its current 70 percent share.

We also see significance in India’s increased emphasis on energy efficiency. The Modi plan aims on this front to reduce the country’s emissions intensity of GDP by 33-35 percent by 2030 relative to 2005, up from it 20-25 percent target by 2020.

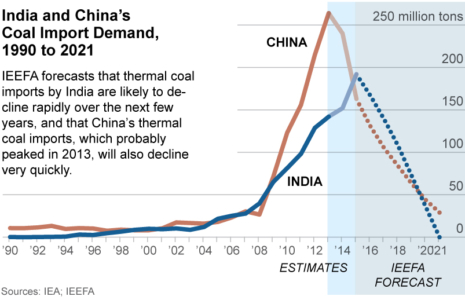

These trends are taking root as the coal-fired power sector in India slips further into financial distress. Utilization rates dropped to a new low of 58.4 percent in July 2015, notwithstanding record-high coal availability, and India’s coal-import appetite is waning. Domestic coal production growth is running at double electricity demand growth of 3 percent year on year so far in 2015-16, and coal imports declined 5 percent year on year in July-August 2015. That’s in line with Energy Minister Piyush Goyal’s pledge to end coal imports altogether.

Renewable energy and energy-efficiency initiatives fulfill a number of objectives for an Indian government focused on providing more energy access to its population and improving poor air quality in its cities. Not only will these policies reduce pollution, they will prove deflationary, meaning they enhance the sustainability of India’s economic development and move the country away from its current fossil fuel reliance.”

While India’s INDC was less aggressive than we anticipated, it makes it clear that the principal of “common but differentiated responsibilities”—CBDR in climate-policy circles—is best understood and best addressed through global financial and technology support, especially for India. Access to international capital is key.

Of note on this point: the two landmark green bond renewable issues last week by ReNew Wind Energy and Hindustan Power, both the first under the credit enhancement scheme of the Indian Infrastructure Finance Company, providing the first loss partial credit guarantee to bondholders along with an irrevocable back-stop guarantee with the Asian Development Bank. The development of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank stands to likewise to accelerate the provision of global capital needed to underpin the Indian infrastructure investment required.

Tim Buckley is IEEFA’s director of energy finance studies, Australasia.