IEEFA India: New National Electricity Plan Reinforces Intent Toward 275 Gigawatts of Renewables-Generated Electricity by 2027

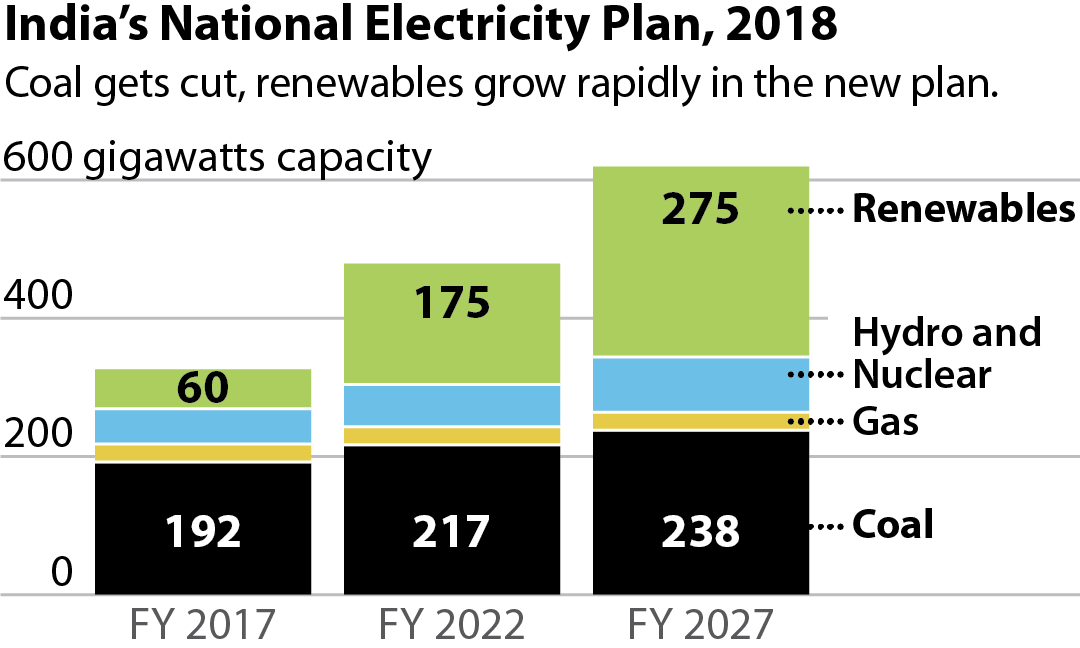

India’s newest power-sector blueprint, the National Electricity Plan 2018 (NEP 2018), reinforces the government’s commitment to transforming the Indian electricity sector, retaining a core target of 275 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy by 2027.

India’s newest power-sector blueprint, the National Electricity Plan 2018 (NEP 2018), reinforces the government’s commitment to transforming the Indian electricity sector, retaining a core target of 275 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy by 2027.

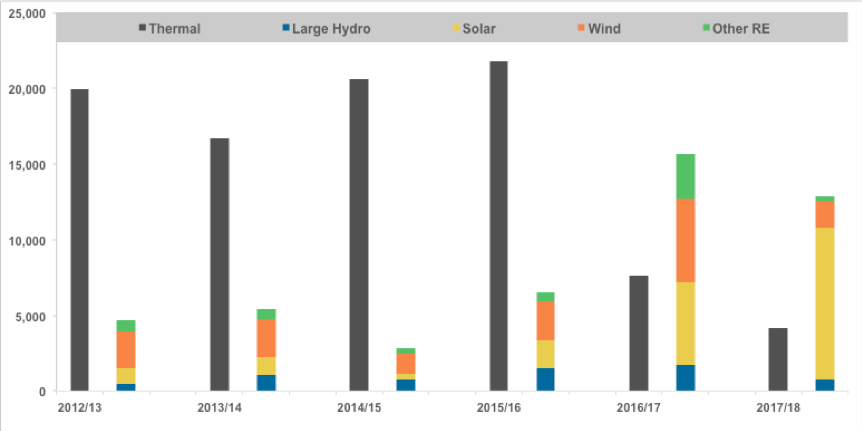

Meanwhile, a Central Electricity Authority data release that tracks the performance of the sector over the fiscal year to March 2018 shows that for the second year running installations of renewable energy capacity were more than twice that of net new installs of thermal power. Consistent with the government’s pollution-control goals, the last two years saw thermal power closures of 6.8 GW while net thermal additions averaged just 6 GW annually, a 70% reduction relative to the previous four years.

Renewables are central to the NEP 2018, which updates a 2016 draft and runs through 2026/27. And while there have been some headwinds to India’s ongoing electricity-generation transition, with wind installations stalling in 2017/18, the overall momentum is positive.

Rapid deflation in the price for both wind and solar power is driving the trend, with tariffs down 50% since the start of 2016. Renewables are now clearly acknowledged as the low-cost source of new electricity capacity.

THE PLAN ALSO INCLUDES A TIMELINE FOR DEALING WITH THE MOST-POLLUTING COAL POWER PLANTS, which should ease concerns about the lack of visible progress to date by the Ministry of Power in terms of tighter air pollution, especially with an apparent five-year deferral of the 2017 deadline for installation of emission controls.

Indications of how momentum and scale is building across India through an offshore-wind push and the world’s biggest solar park.

The NEP 2018 includes a new target for closure of 48.3 GW of end-of-life coal plants. Specifically, the plan forecasts 22.7 GW of coal power plant closures over the five years from 2016/17-2021/22. This would include 5.9 GW of normal end-of-life retirements and 16.8 GW of closures due to inadequate space for flue gas desulfurization equipment. The plan notes that these retirements “would not likely pose any problem in meeting the demand (for electricity) during 2021/22.” An additional 25.6 GW of coal capacity is slated for retirement in the five years to 2026/27.

Taking these retirements and planned new construction totaling 94.3 GW into account, the NEP 2018 sees India’s coal power capacity hitting 238 GW in 2027, 11 GW lower than the 2016 forecast.

Given that India’s economy is forecast to grow significantly over the coming decade, with gross domestic product rising 7-8% annually, the government expects electricity capacity needs to nearly double to 2027. With accelerated coal plant closures, and an anticipated surge in renewables, thermal power will account for only an estimated 42.7% of installed capacity across India by 2027, down dramatically from 66.8% in 2017.

THESE TRENDS, AND THE MARKET FORCES DRIVING THEM, represent a major challenge for the coal power sector, given that plant load factors (PLFs) are forecast to average just 56.5% in the next five years, rising marginally to 60.5% in the five years to 2027 (a 60.5% PLF equates to a coal plant utilization rate of just 58%). The plan concludes further that coal power plants will require retrofitting and reengineering to meet a much more variable demand profile going forward.

It also has thermal coal imports falling to 50 million metric tons annually (Mtpa) by 2021/22, a decline of two-thirds, and then holding steady through 2027 at much lower level than anticipated by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and other coal industry boosters.

Total thermal coal requirements for power generation by 2027 are estimated at 877Mtpa. This would put domestic thermal coal production at 827Mtpa, well short of the 1,500Mtpa production target trumpeted just two years ago—even after accounting for non-power uses.

ONE OF THE KEY UPDATES IN THE NEP is its adoption of the assumption that hydroelectricity generation will decline by 30% over the next decade because of climate-change impacts of monsoon flows.

The plan highlights the importance of moving quickly to address climate change, which is a fundamental shift in the narrative, acknowledging as it does that coal will continue to be used for electricity generation but only to the extent India cannot procure sufficient power from its many zero-emission alternatives.

The plan’s reinforcement of the government’s intent to build out 275 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2027—which would amount to 44% of the country’s total capacity and 24.4% of its generation—makes that goal increasingly attainable in the wake of accelerated tendering activity spurred by the Ministry of Power’s plans for 30 GW annually of solar tenders this year and next.

Despite a slow 2017/18 in the wind sector, with just 1.74 GW commissioned nationally, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy is planning for an additional 10-12 GW annually of wind generation going forward, including 6.5 GW tendered in the first quarter of this year.

One indication of how momentum and scale in renewables activity is building across India: plans announced just this month by the state of Gujarat to hold a 1 GW offshore wind tender followed by approval there for a US$4bn, 5 GW solar park on 11,000 hectares in the Dholera Special Investment Region. That project would be by far the largest solar installation globally, more than double the Bhadla 2.2-GW Industrial Solar Park in Rajasthan.

India’s Electricity Net Additions (FY2013-FY2018)

Source: CEA, IEEFA calculations

All in all, the NEP 2018 offers India a guide to a system-wide transformation over the decade ahead, AND puts the country in a position of global renewable-energy leadership.

Tim Buckley is IEEFA’s director of energy finance studies, Australasia. Kashish Shah is an IEEFA research associate.

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA Update: Tamil Nadu Is on a Renewables Roll

IEEFA China: A ‘Sea Change’ in Energy Policy

IEEFA Update: India Is Becoming a Transition Force on Par With China and Western Europe