IEEFA Georgia: The diminishing importance of coal-fired power generation

IEEFA released a report in November 2015 calling for Southern Co. and its subsidiary Georgia Power—out of respect for investors and ratepayers—to retire the four-unit Plant Hammond coal-fired power station.

The report pointed out how flat demand had diminished the need for the plant’s generation capacity and that its electric output was being priced out of the market by lower-cost natural gas and, increasingly, no-fuel-cost solar and wind power.

Since then, Plant Hammond’s capacity factor (the amount of electricity produced compared to a plant’s potential) has continued to decline, dropping from 15.73% in 2015 to just 6.7% in 2017. No upward movement is likely this year either: Through the end of September, the plant operated during only two of the first nine months of 2018.

Plant Hammond, situated near the Alabama state line in northwest Georgia, is no anomaly. It reflects broader developments by which coal plants, long thought of as the baseload bulwark of the U.S. power-generation sector, are no longer functioning as such. Instead of running flat-out full time, many coal-fired units are being used to follow daily swings in load while others hardly operate at all in the spring and fall and then are used essentially as peaking units during high-demand periods in summer and winter.

A tale of two plants that sit idle more and more of the time.

This transition has been under way for the past decade and generally has followed a two-step progression: First, driven by huge increases in natural gas supplies and sharp declines in prices, utilities have turned for baseload generation to gas-fired power, particularly efficient combined cycle facilities, in lieu of coal.

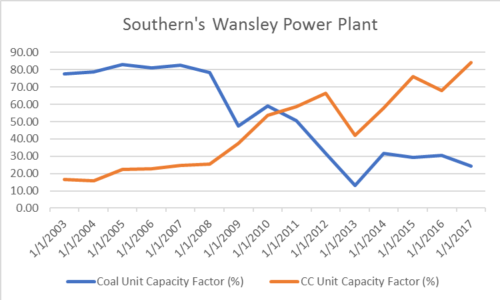

Southern’s Plant Wansley complex 60 miles southwest of Atlanta graphically illustrates this transition. Wansley includes two supercritical coal-fired units owned by Georgia Power that entered commercial service in 1976 and 1978. The two units have identical net summer capacity ratings of 872 megawatts (MW).The complex also includes two combined cycle natural gas units owned by Southern that came online in 2002 and have a combined summer capacity of 1,150MW.

The first chart below shows how Wansley is a microcosm of changes that have swept the utility industry. From 2003 to 2008, Wansley’s coal units operated at a capacity factor of near or above 80%, while the gas units operated at less than 30% of capacity. Gas price declines and revised perceptions about long-term stable supplies that began to take hold in 2008 have turned the equation upside down. Since 2014, the gas-fired units have posted an average capacity factor of slightly less than 65%, and are on track to be well above 80% this year. The coal-fired units at Wansley have operated at or below 30% of capacity since 2012, and may not average 20% this year.

Source: S&P data, IEEFA

The Wansley complex is not an outlier. According to S&P data, Southern operated 16,527.9MW of coal-fired capacity at 16 plants in 2010; those facilities posted a combined capacity factor of 64.31% that year. By 2017, the company had retired six of those plants, cutting its operating capacity to just under 13,000MW—and still the average capacity tumbled to less than 46%. Just as telling, six of the 10 still-operating plants in 2017 posted average capacity factors below 40%, with two at less than 10%, including Hammond.

Nor is Southern’s experience unique. Our research indicates that of the 102 largest coal-fired power plants in the U.S., 93 posted a lower capacity factor in 2017 than they did in 2007. On the whole, the declines were pronounced: 37 of these plants recorded capacity-factor drops of more than 25% while 38 fell by at least 10%.

THE SECOND PART OF THE TRANSITION, BEYOND THE BROAD SWITCH FROM GAS TO COAL, involves the increasingly low cost of renewable energy, especially solar and wind, a trend that is beginning to have an impact on generation dispatch decisions in Southern’s service territory.

The full impact on this front will likely take several years to materialize, but the direction of change is clear, and it is not to coal’s benefit.

Non-hydro renewables historically have been only a small component of the generation mix in Georgia, but that is changing quickly. In 2013, the Georgia Public Service Commission directed Georgia Power to begin adding solar to its mix, and the utility now has roughly 1,000MW installed statewide. Plans are for the utility to add an additional 1,600MW by 2021, and a request for proposals released just this week calls for 540MW of new renewable capacity through Georgia Power’s renewable energy development initiative.

Every megawatt of solar and wind added to the grid has a direct impact on other installed generation, especially on coal and to a lesser extent natural gas, because those renewable megawatts have zero fuel costs and have extremely low variable operations and maintenance expenses. They will always be dispatched first.

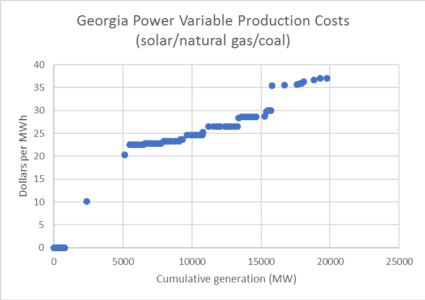

The two figures below illustrate the effect on Southern’s coal units. The first chart graphs the variable costs of Georgia Power’s generation, looking specifically at the utility’s solar, natural gas and coal-fired plants. The small group at the bottom left of the graphic is made up of the utility’s existing solar, the large block between $20-$30 per megawatt-hour (MWh) largely encompasses its natural gas combined cycle generators, and the dots starting at $35/MWh include Southern’s coal units and simple cycle gas plants. The graphic does not include the utility’s four nuclear units, which come in around $10/MWh, further undercutting coal’s viability. The Wansley combined cycle units discussed above have variable costs of roughly $22/MWh while the two Wansley coal units’ variable costs are above $37/MWh, essentially in line with the last dots on the upper right of the chart.

Source: S&P data, IEEFA

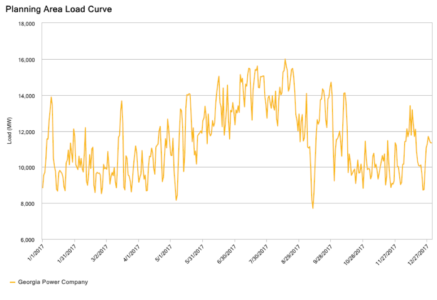

The second figure here shows Georgia Power’s daily peak demand for 2017, a year in which demand topped 16,000MW only once. Wansley’s coal-fired units fall at 20,000 MW in the utility’s economic dispatch supply curve, suggesting that the units will only be used during periods of exceptionally high demand.

Daily Peak Load for Georgia Power (2017)

Source: S&P

Put the two charts together and a huge problem is apparent not just for the Wansley coal units but for Southern’s other high-cost coal-fired generation too. Only on the coldest and hottest of days, or when another cheaper plant is offline for maintenance or other reasons, is there any need for these plants—and their presence even in that respect is becoming increasingly unimportant.

Again, Wansley illustrates the point: During the first nine months of 2018, it operated at less than 10% capacity during five of those months. At Hammond, which has much higher production costs than Wansley, the story was even worse—the plant has operated during just two of the past 12 months.

While neither Hammond nor Wansley are technically retired, they represent how high operating costs for coal-fired generation puts such plants at increasing risk of sitting idle more and more. Given current projections for low-cost natural gas and the rising profile of new renewable generation, this trend will almost certainly gain further momentum.

Dennis Wamsted is an IEEFA editor.

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA Study: Georgia Power Should Retire Plant Hammond

IEEFA U.S.: Transition to renewables has taken hold in historically coal-dependent northern Indiana

IEEFA report: U.S. likely to end 2018 with record decline in coal-fired capacity