IEEFA: Deploying batteries at scale in the Indian power sector

India needs to deploy batteries at scale in the power sector.

The country envisages uptake of 450 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy capacity by 2030. The high penetration of intermittent renewable energy will bring up issues around managing system flexibility in terms of steeper ramps and peaking load requirements.

System flexibility has historically been met by coal-fired power

In India, system flexibility has historically been met by coal-fired power plants. India also plans to install 50GW of new coal power capacity during 2022-27, according to the Central Electricity Authority.

As an alternative, battery energy storage systems (BESS) based on lithium-ion batteries could be used. System flexibility needs due to 450GW of renewable energy could be met by 50GW of 4-hour energy storage. Renewable energy along with BESS could then provide a clean, affordable and sustainable alternative to coal-based power generation technology.

Recently, the Government extended the transmission charges waiver for renewable energy developers including BESS to 2025 which would enhance their cost-competitiveness. There are other regulatory changes afoot, for instance, time-of-day (TOD) pricing which is expected to monetize the value of services provided by BESS. However, India lacks procurement frameworks which could unlock the benefits of BESS.

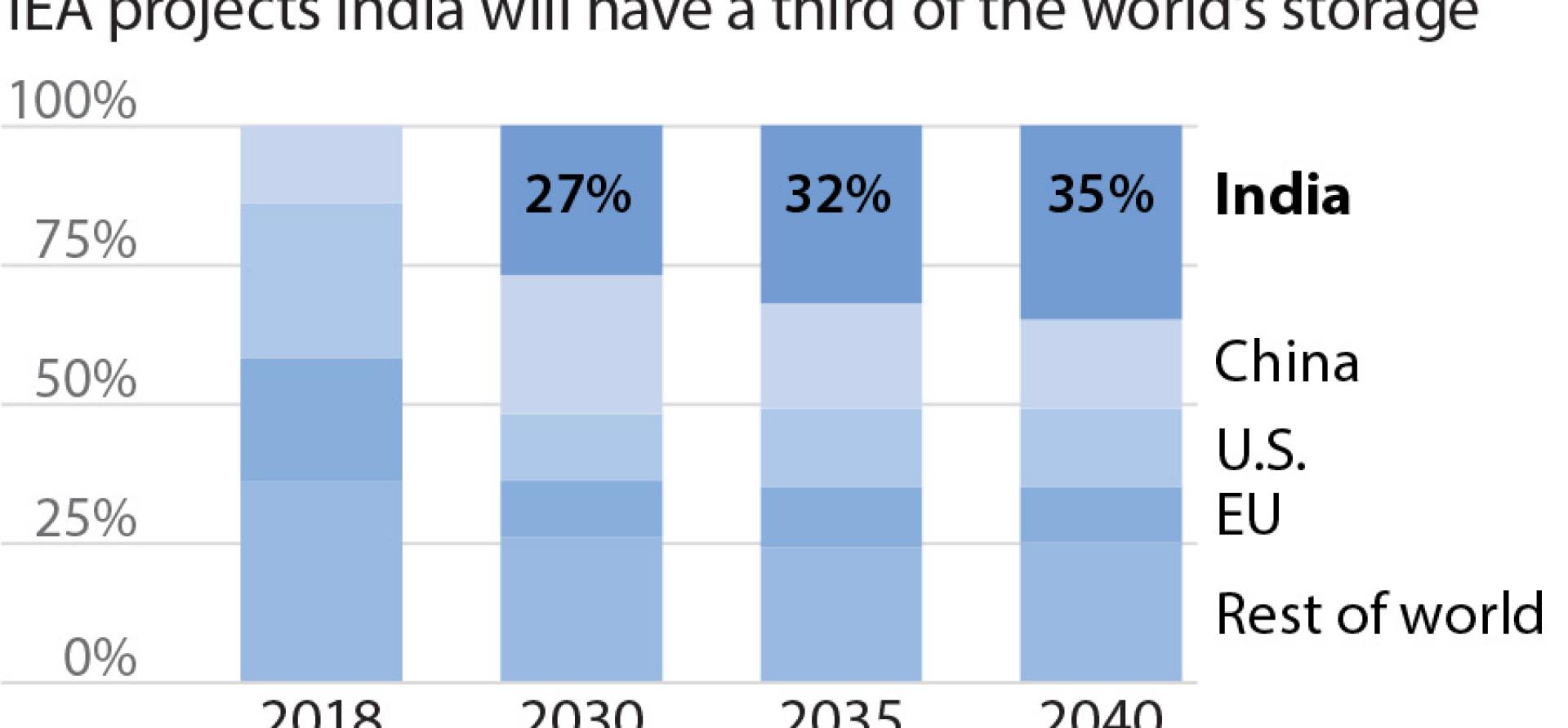

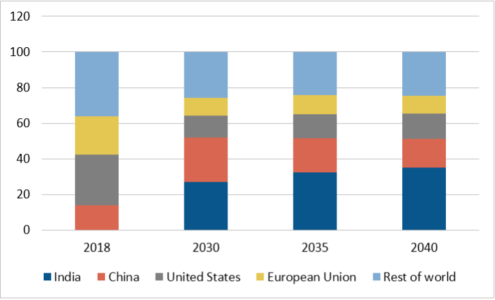

Besides being faster to deploy at scale, batteries can also quickly ramp up and down their output, thereby proving more effective in meeting system flexibility requirements than conventional coal plants. As shown in Figure 1 below, the International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that India’s share could reach one-third of global share in BESS deployment by 2040.

Figure 1: India’s Share in Global BESS Deployment

Source: IEA

Going forward, India needs a well-defined policy framework to not only create a market for BESS but to also ensure procurement. In this piece, we examine appropriate policy design by answering a few related questions.

What is the cost-competitiveness of renewable energy plus BESS compared to new coal power?

In a recent study, we estimated the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for different generation technologies on a LCOE basis, with LCOE being the average cost of generation over the economic life of the generation source.

From 2023, solar plus BESS will be cheaper than any coal power

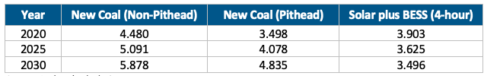

We found that by 2030, solar plus BESS has the lowest levelized cost at Rs3.496/kWh, followed by pithead coal power at Rs4.835/kWh and non-pithead coal power at Rs5.878/kWh. By pithead, we mean a coal power plant located at the mine, so transportation costs are avoided.

From 2023, solar plus BESS will be cheaper than any coal power – pithead as well as non-pithead. That is, there is a clear economic case for not building any new coal-fired power plants after the current 5-year plan (i.e., 2017-2022).

Further, solar plus BESS is already cheaper than non-pithead coal power highlighting the energy transition already underway in the Indian power sector. Consequently, at-scale deployment of BESS along with the higher uptake of renewable energy could emerge as the more cost-effective provider of electricity in the market.

Table 1: Levelized costs – New Coal vs Solar Plus BESS

Source: Authors’ calculations.

How does India ensure the required deployment of BESS given its renewable energy targets?

For scale deployment of BESS in India, there needs to be clear and long-term policy signals on market demand for BESS. In addition to minimization of regulatory risks, investors expect a set of transparent, long-lived, and comprehensive policies.

BESS could facilitate renewable energy integration with ease

The experience of Hawaii and California in the U.S., which include mandatory targets for storage, has shown how BESS could facilitate renewable energy integration with ease. For example, California has mandated that utilities procure BESS according to capacity targets.

We posit that BESS procurement should follow the establishment of a national BESS target (e.g., 50GW/200GWh by 2030) and corresponding BESS targets termed as Battery Portfolio Standards (BPS), like the well-known Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS). This would then need to be shared among states based on their anticipated flexibility requirements.

Karnataka, Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Madhya Pradesh are the leading states in both solar and wind capacities. In addition, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh, and Punjab are other leading states with solar capacity alone. These states are more likely to need higher system flexibility and therefore, should take a lead in implementing BPS.

How do we procure BESS while addressing system flexibility issues?

For all new technologies including BESS, a well thought-through procurement policy framework is critical in ensuring at-scale adoption. Renewable energy plus BESS should not only be procured under long-term, fixed price contracts (contracts in the power generation industry are also referred to as Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs)), it should also be dispatchable for energy as well as ancillary services. The contract would minimize investor risk perceptions and deliver renewable energy plus BESS at least cost, while dispatchability would address system flexibility issues.

Renewable Dispatchable Generation (RDG) PPAs is one such innovative contract used by utilities in Hawaii.

While in conventional PPAs generators get paid for dispatched energy, in RDG PPAs the payment is fixed based on expected generation. In case of curtailment, conventional PPAs allow partial recovery of costs, thereby increasing the risk borne by the generator. In contrast, in RDG PPAs curtailment risk is evenly shared between the generator and the utility.

Curtailment risk is shared between generator and utility in the Hawaiian model

As a result, most of the new solar generation in Hawaii is under RDG PPAs as the reduced financial risk allows for reduced project financing costs and better investment opportunities.

Using an RDG PPA, a discom in India would pay a generator a fixed monthly amount based on potential energy output. Further, the discom would have the right to control the output of the generator which must be maintained according to the contract, failing which penalties could be invoked. Thus, the discom would be able to efficiently provide required system flexibility.

In sum, for improving the commercial case of BESS, mandatory deployment targets by states and innovative procurement mechanisms need to be in place, suitably complemented with an innovative RDG procurement model.

Gireesh Shrimali is a Precourt Scholar at the Sustainable Finance Initiative, Stanford University. Abhinav Jindal is a PhD in Economics from Indian Institute of Management Indore and is working as Senior Manager (Commercial), NTPC Ltd.

This article first appeared in the Economic Times.

Related items:

IEEFA India: Coal-dependent power producers should prepare for climate transition risk

IEEFA: India’s battery storage market is a sleeping giant

IEEFA: India should focus on reducing coal power generation instead of capacity

IEEFA: India may face unbudgeted energy transition risk of nearly $9 billion