Federal mandate to build Mountain Valley Pipeline doesn't change poor market potential

Key Findings

An appeals court order that stays construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline may prevent a dangerous precedent

A provision in federal debt ceiling legislation could force consumers to foot the bill for a costly and unnecessary project

Market forces are moving in a direction that will not benefit the pipeline. Lower-cost, pollution-free renewable energy is a better option

The future of the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) remains in jeopardy, despite passage of a federal legislative mandate requiring permit approvals for the controversial project and barring appeals.

An appeals court panel on July 10 granted a motion to stay construction of the MVP in the Jefferson National Forest while it considers a legal challenge to Section 324 of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 (the negotiated debt ceiling package) and a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service review of the pipeline’s impacts.

Section 324 ratifies pre-existing federal approvals of the MVP—regardless of whether they violate the underlying laws—and simultaneously strips court jurisdiction to hear challenges to the approvals. It applies even for litigation already pending at the time the legislation was enacted.

The MVP provision in the debt ceiling package poses a dangerous precedent. Overriding a pipeline permit process can force energy consumers to pay for a costly, unnecessary project. It would also allow pipeline developers to launch eminent domain actions against private landowners where the actual necessity of the taking has not even been analyzed, let alone proven in a public forum. Landowners who resist would have to take legal action.

A friend-of-the-court brief filed by four legal scholars amplified the environmental petitioners’ argument, stating Congress violated the separation of powers doctrine of the U.S. Constitution when it directed the result in pending MVP litigation without amending substantive law. They argued the debt ceiling bill unfairly picked a winner in ongoing litigation.

The appeals court’s stay of construction does not explicate the judges’ reasoning, but one of the standards for issuing such an order is a finding of probable success on the merits.

The federal mandate does not serve the energy-using public.

Gas utilities that serve the public are not the dominant force behind the MVP project. More than three-fourths of the pipeline’s capacity have been contracted by natural gas companies, including EQM Midstream Partners and NextEra Capital Holdings, which have profit motivations that do not always serve the public interest.

The contractual capacity has not become more customer-driven over time. Rather, one of the utilities, Consolidated Edison, exercised a provision in its contract in 2019 that allowed it to cut its share by one-fifth, down to under 10%.

The main driver of the pipeline remains gas supply businesses seeking a larger market for fracked gas from the Marcellus and Utica shale fields.

Market forces are moving in a direction that will not favor the MVP.

Natural gas, once the only game in town, increasingly has to compete with more stable, lower-cost wind and solar energy, while heat pump technology and other efficiency measures chip away at gas heating demand.

International demand also is not proving to be as deep a pocket as some may have hoped in the wake of the market disruptions generated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. IEEFA’s Global LNG Outlook 2023 report warns of the potential for a market glut in liquified natural gas (LNG) exports between 2025 and 2027. The report cites high global LNG prices, declines in gas consumption in Europe, price sensitivity in Asia and global investments in cost-competitive alternatives. A subsequent IEEFA review found that Asian demand continued to fall in the first quarter of 2023 despite lower global prices.

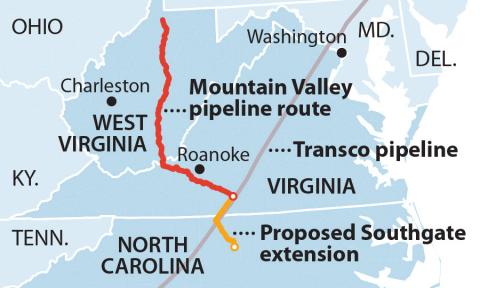

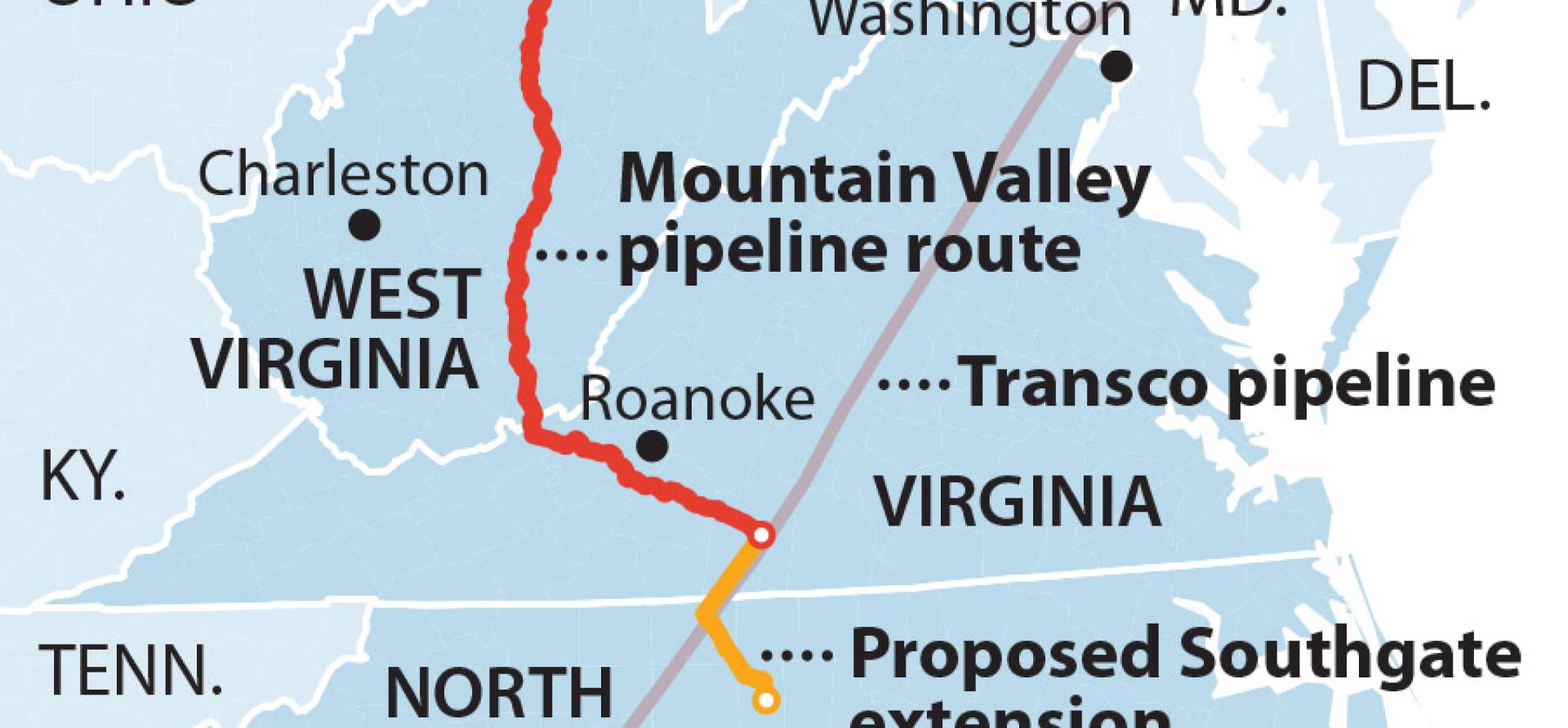

Questions also have arisen about how much gas the MVP would actually carry. Analysts from both S&P Global Commodity Insights and analytics firm East Daley Capital point out that the Transcontinental Gas Pipeline—a southern Virginia connection point for the MVP—has limited spare capacity. These constraints matter: East Daley argues that downstream limits mean that MVP mostly provides “phantom” capacity, and would operate at only 35% capacity if built. If the influx of MVP gas to the system dampens prices, the economics of the pipeline may not work in producers’ favor.

The challenged Section 324 mandate does not change the fact that federal agencies never independently examined the pipeline’s need, or that the various court rulings that held up MVP construction before passage of the debt ceiling legislation were based on well-reasoned findings that agencies had given short shrift to serious factual environmental disputes. One cannot simply declare away the fundamental issues that have made the pipeline so controversial.

Regardless of how this legal battle is resolved, market forces are likely to continue to erode the financial viability of the Mountain Valley Pipeline.