Mountain Valley Pipeline debt deal undercuts U.S. governing values

Key Findings

A debt-ceiling deal would require federal agencies to approve the Mountain Valley Pipeline and prevent citizens from contesting its decision.

The proposed legislation is being considered even as a glut of natural gas is developing in international export markets.

Federal regulators already have failed to consider whether the pipeline is actually needed, basing their decisions on contracts by the sponsor’s affiliates.

Permit reform that pushes through an unneeded, harmful and costly project isn’t reform; it’s a distortion of the government decision-making process.

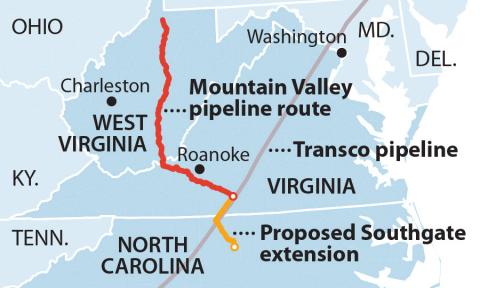

The proposed Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP), a project to move fracked gas from West Virginia to Virginia, has become a high-profile political football in the national debt ceiling debate. The proposed debt-ceiling deal not only would require agencies to approve the pipeline but also seeks to prevent the public from being able to contest decisions in court.

The MVP does not pose a national security issue that requires it to be crammed into the debt ceiling deal. A federal court last year rescinded certain authorizations for the MVP only after finding agencies gave short shrift to serious factual issues that needed review. Meanwhile, the domestic energy system targeted by the pipeline has continued to function for almost a decade without the project, and international export of gas is trending toward a glut rather than a shortage.

The ill-advised plan to override the MVP public permit process and the right to judicial review undermines U.S. government principles. It’s a bad way to make decisions on a gas project.

Domestic and international market conditions do not justify taking away the right to public review of the MVP

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) did not directly evaluate the market need for the MVP. Instead, it relied on the existence of shipping contracts even though—as IEEFA has noted— four of the five shippers were corporate affiliates of the project’s sponsors. A federal court allowed that approach in 2019. Last year, MVP requested an extension until Oct. 26, 2026, to complete the pipeline. In granting the extension, FERC refused to re-examine the pipeline’s necessity, relying instead on inadequate, obsolete information.

But both domestic and international market conditions have changed in ways that challenge the pipeline’s rationale.

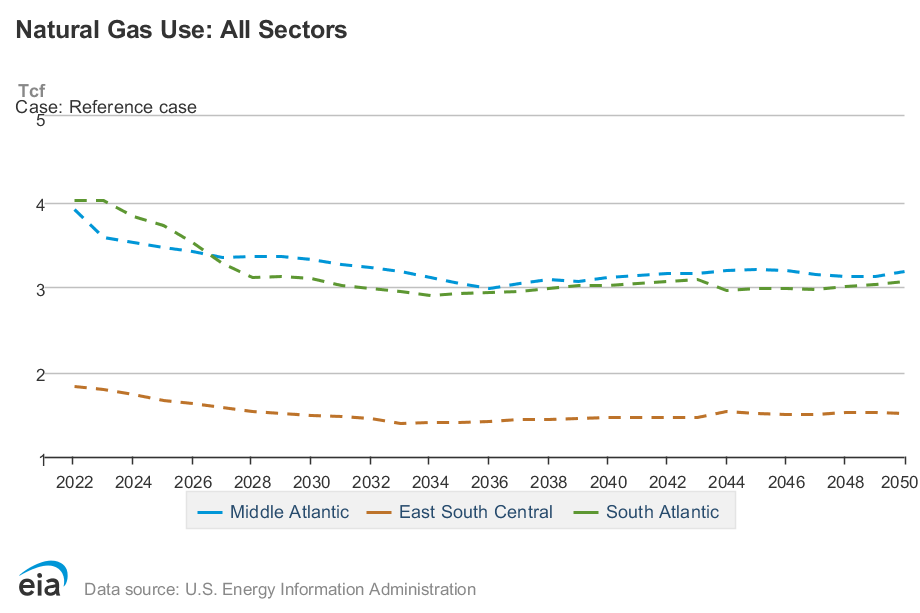

In a 2021 report IEEFA documented that forecasts for domestic gas demand had declined since FERC’s 2017 approval of the pipeline. In its Annual Energy Outlook 2023, the U.S. Energy Information Administration projected that domestic gas consumption for electricity generation is likely to decrease by 2050. EIA regional projections for all natural gas use sectors do not indicate future increases.

Economics that might have made the project’s gas attractive have shifted. Based on data from S&P Global Capital IQ, the price differentials between Dominion South and Transco Zone 5 appear to be narrowing, which could make the pipeline less desirable for utility customers. Also, the MVP’s estimated construction costs have risen from $3.7 billion to $6.6 billion.

The future of the proposed MVP Southgate Extension into North Carolina is uncertain. AltaGas, with a 5 percent equity interest in the extension project, has disclosed that it impaired its investment in the MVP Southgate project “to a carrying value of $nil” in the fourth quarter of 2021. The developer is reconsidering the project’s design, scope and timing, which calls into question the MVP’s value for the Public Service Co. of North Carolina, a subsidiary of Dominion Energy.

The international market does not appear to need the MVP. IEEFA’s Global LNG Outlook report released earlier this year warns of the potential for a market glut in liquified natural gas (LNG) exports between 2025 and 2027, given high global LNG prices, declines in gas consumption in Europe, price sensitivity in Asia and global investments in cost-competitive alternatives.

The MVP would connect with the Transco pipeline system, which can carry gas to LNG export terminals in the Gulf Coast. MVP developers have suggested gas could be exported to India, but glut conditions likely would appear by the 2026 construction deadline. Even if the MVP opened by the company’s predicted late 2023 date, the export market shift would likely affect its profitability.

These market conditions do not justify forcing decisions on both state and federal agencies under federal law or revoking the public’s right to judicial review of agency action.

The pipeline permit system is reasonable and should not be undermined

The permit system is not stacked against pipeline developers. It is almost always easier for an agency to say “yes” to a project than “no.” Neither landowners nor community advocates have the advantage in court. The Administrative Procedure Act requires the court to uphold an agency action unless it is unconstitutional, exceeds the agency’s jurisdiction, or is “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law.” A case must be strong to meet the standard.

Criticism of the environmental impact statement process under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) appears to be based on industry folklore. Federal agencies have prevailed at the federal appellate court level over the past 10 years in an average of 83% of NEPA cases.

A government permit process that affords public scrutiny backed up by the right to judicial review forces decision-makers to think about more prudent alternatives. It promotes competent government.

Not every proposed project should be built.

A permit denial or court decision on appeal that blocks an ill-advised, harmful, costly, unnecessary project benefits the public. So-called permit “reform” that pushes through a project that presents excessive environmental harms or costs regardless of lack of public need is not real reform. It’s a distortion of the government decision-making process.

It’s a bad idea.

It should not have been on the table in the debt negotiation. It should not be in the final legislation.