Even as “LNG Pause” ends, DOE still needs to update costs and consequences of export surge

Key Findings

Federal court LNG pause ruling relied on same outdated reasoning that DOE promised to update

Increased volatility caused by soaring LNG exports continues to cost domestic consumers

Exporting LNG takes the nation further away from its emissions targets, not closer to them.

DOE should update its analysis of costs and consequences of LNG export surge

Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) announced it would temporarily pause its processing of new applications to export liquefied natural gas (LNG) to nations that did not have a free trade agreement with the United States. The agency explained it would use the pause to refresh outdated analyses of the economic and environmental effects of natural gas exports.

But at the beginning of July, a federal district court in Louisiana ordered DOE to end the pause and restart its review of LNG export applications. The court’s ruling relied on the same outdated reasoning that DOE had pledged to update. If it had examined more recent data, the court might have come to a different decision.

Regardless of what happens in the litigation, DOE cannot continue to base its decisions on outdated, inaccurate information. The agency’s announcement of the pause explained:

“As the natural gas sector has transformed over the past decade, DOE must use the most complete, updated, and robust analysis possible on market, economic, national security, environmental considerations, including current authorized exports compared to domestic supply, energy security, greenhouse gas emissions including carbon dioxide and methane, and other factors.”

Agency commitment to factual accuracy is even more important today, given that the U.S. Supreme Court recently eliminated the mandate for courts to defer to reasonable agency interpretations of ambiguous federal statutes.

Whether DOE’s review of the impact of LNG exports is conducted in a particular project review or by developing a new policy document, as DOE was planning to achieve through its pause, the updated analysis must occur.

The studies DOE has been using to evaluate the effects of LNG exports were written when the U.S. LNG export industry was in its infancy. The effects of LNG on domestic consumers, local communities, and the climate were largely unknown.

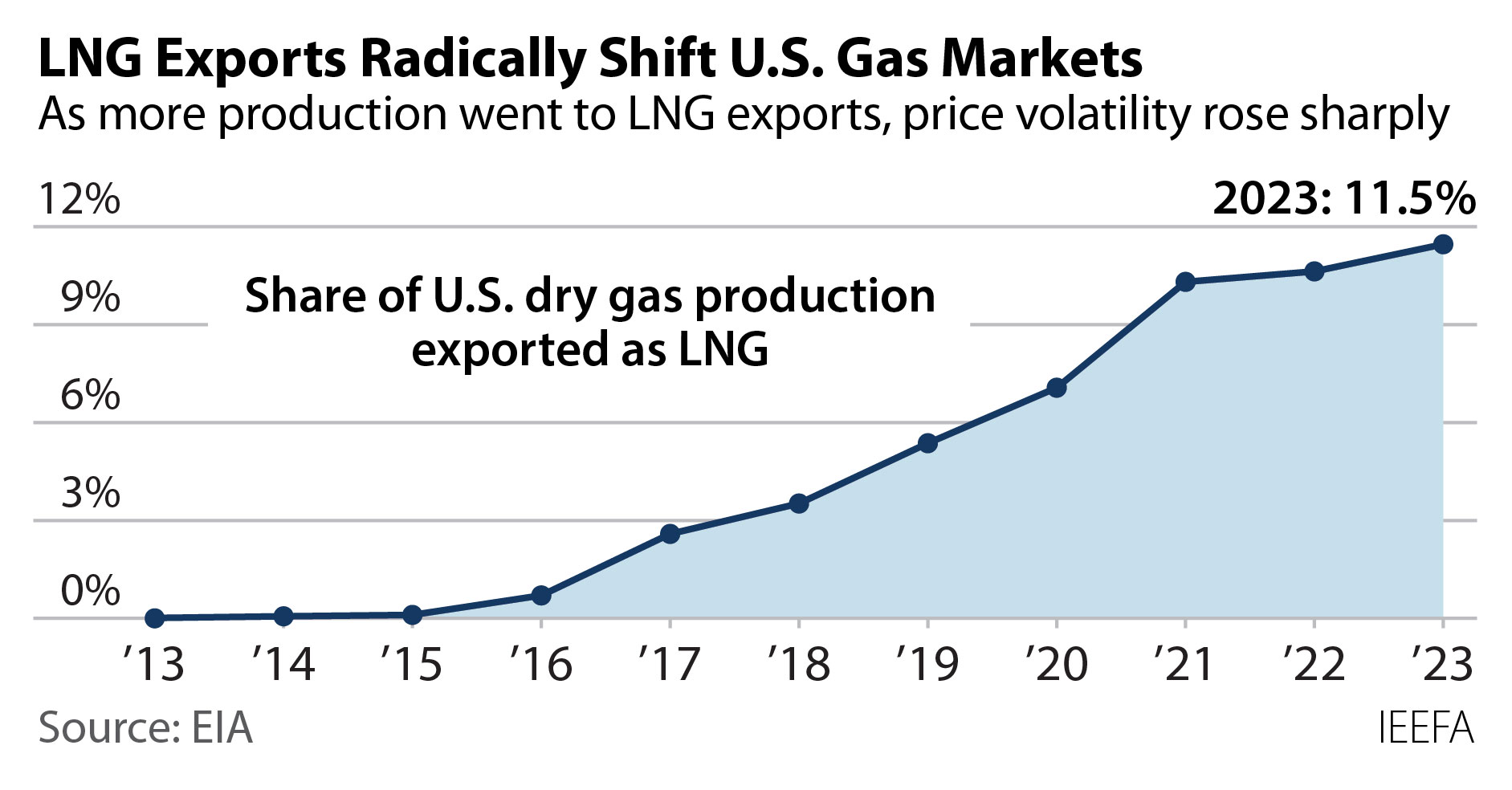

But domestic gas markets have changed radically since those studies were conducted. Starting from near-zero at the beginning of 2016, U.S. LNG exports have skyrocketed to about 12% of total natural gas production in the country.

As LNG exports have grown, consumer costs for gas have spiked as well. In early 2021, winter storm Uri caused a supply shock that sent natural gas prices from $3 to $1200 per thousand cubic feet, as a Texas freeze also slashed production. In Oklahoma, customers will pay several dollars more per month for at least two decades to cover the losses experienced by one of the state’s utilities. Later, the invasion of Ukraine set off a price war between domestic consumers and gas exporters, sending U.S. gas prices to their highest level in a decade.

IEEFA analyses have demonstrated that U.S. consumers are paying more for gas, and the gas is subject to much higher price volatility. For example, our research showed that the Russia-induced price spikes cost U.S. households and natural gas buyers more than $100 billion in 2021 and 2022. DOE’s outdated studies never contemplated a price surge of that magnitude.

The old studies on which DOE relies also used its National Energy Modeling System (NEMS) to project outcomes for additional LNG exports. The NEMS models are complex, but they have no mechanism to incorporate exogenous shocks—such as a major winter storm or war—into their projections. Consequently, the modeling system is ill-suited to provide guidance on how price volatility changes as LNG export grows.

Compared to the seven years before 2016, the benchmark Henry Hub spot price for domestic natural gas has seen its volatility double. These price swings are passed along to consumers—not just in their gas bills, but also in electricity bills, because natural gas is the largest source of fuel in the electricity generation power stack. Gas volatility has translated into higher prices for consumers that do not go away quickly when volatility subsides.

Volatility could get more severe as LNG exports grow.

With five major LNG export projects already under construction, and completely unaffected by DOE’s pause, the U.S. will see export volumes almost double over the next five years—based solely on already-permitted capacity.

Lifecycle air emissions from LNG activities are also significantly understated in current DOE analysis. Over the last decade, leak detection technologies have improved, and research has proven that methane releases from the entire natural gas supply chain are far higher than previously thought. Without even accounting for boil-off gas losses, LNG export terminals increase emissions by 15% compared to natural gas usage that does not employ liquefaction and regasification. Furthermore, the feed gas for LNG export terminals on the Gulf Coast is delivered from regions with higher methane emissions than the national average.

Exporting LNG takes the nation further away from its emissions targets, not closer to them.

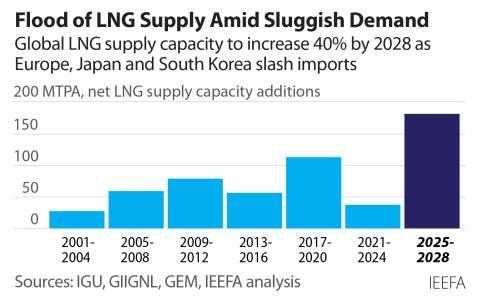

As U.S. exports have boomed, global markets have evolved. Europe’s demand for LNG spiked in 2021 and 2022 but has fallen since. IEEFA research suggests Europe, Japan and South Korea—which together account for more than half of the global LNG market—will see a long-term decline in demand for the fuel.

Meanwhile an unprecedented volume of LNG supply is under construction around the globe. Rising supply coupled with weak demand raises the specter of a global LNG supply glut that could render some U.S. export capacity superfluous. Surely, the DOE calculus for what is economically in the public’s best interest would change if the agency considered the potential that LNG exports could turn into a financial albatross.

Eight years of LNG export growth in the U.S. have led to higher and more volatile utility costs for U.S. consumers, increases in methane emissions and questionable economic benefits. Greater scrutiny of new projects is warranted. Pause or no, DOE has a duty to update how it analyzes the costs and consequences of the ongoing surge in LNG exports.