The energy transition in India – onwards and upwards

It seems that the energy transition in India has just turned a corner.

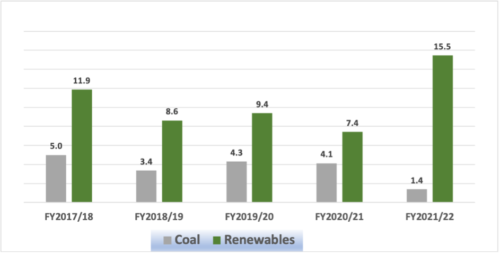

After a tough three years filled with policy headwinds, policy obscurity, and the COVID-19 pandemic choking growth in the capacity of renewables, a record high of 15.5GW of renewables capacity was added in fiscal year (FY)2021/22.

This includes record solar capacity installations of 13.9GW in a year. India’s total renewable energy capacity now stands at 110GW.

On the other hand, coal power capacity additions hit rock bottom in FY2021/22. Only 1.4GW of net new coal capacity was added during the year, taking total coal capacity to 211GW. A total of 4.4GW of gross new coal capacity was commissioned and 1.5GW of end-of-life coal capacity was retired (1.5GW of capacity was converted to behind-the-meter captive use).

Coal vs Renewable Capacity Additions FY2017/18 to FY2021/22

Source: CEA, IEEFA

Duty-free period

As India’s solar industry has been heavily dependent on imported modules from China and Chinese-owned companies operating in other Asian markets, the Indian Government imposed duties to protect domestic industry. However, the duty had an upward impact on solar tariffs, which slowed down capacity commissioning.

In the FY2020/21 fiscal budget announcement, the Ministry of Finance imposed a basic customs duty (BCD) of 40% on imported solar modules and 25% on solar cells from China, effective April 2022, while the previously imposed safeguard duty ended in July 2021. Developers used this brief window to their advantage and improved cost competitiveness.

Solar developers in India also enjoyed a “duty free” period of eight months between August 2021 and March 2022 for solar cell and module imports from China and other Asian markets. Through timing their module imports the developers accelerated project commissioning.

A boost to domestic solar module manufacturing

These duties have sought to protect the domestic solar module manufacturers, which have struggled to compete with the scale and technology of the Chinese manufacturers. The Government of India sees solar module manufacturing as a huge opportunity to create job opportunities while reducing import dependence, necessary for India’s energy needs.

It carried out the first round of the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme, pegged at Rs24,000 crore (US$3.2bn), in February 2022. The scheme attracted industry giants such as Reliance, Adani and Shirdi Sai Electricals to set up a fully integrated module manufacturing capacity of 12GW.

India’s domestic cell manufacturing capacity is projected to be 33GW and for modules, 51GW by 2025 (JMK Research, IEEFA). This would potentially reverse the reliance on imports and create export capability for solar modules.

Investments need to accelerate in renewable energy

The renewable energy sector attracted investments in excess of US$15bn in FY2021/22, largely for generation assets. This includes green bonds worth US$4.7bn and debt worth US$1.8bn from domestic and foreign lenders.

There is more than 50GW of renewables capacity currently under development including projects tendered, auctioned and under construction. Capacity commissioning of about 16GW is expected in FY2022/23 (ICRA).

India’s giant target of 450GW by 2030 needs a capacity commissioning rate of, on average, 35-40GW annually with annual investment of US$35-40bn in generation, transmission and storage assets.

Coal outlook

There is 55GW of coal capacity in India’s pipeline (as of January 2022) according to Global Energy Monitor (GEM) data. Of this, 31GW is under construction and the remaining 24GW is in various stages of planning and regulatory approval.

A staggering 607GW of planned coal power projects have been cancelled or shelved since 2010, according to GEM. And given the challenges, most current projects will not see the light of the day.

Investors and lenders have turned their backs on coal power projects as lower-cost and clean renewable energy puts increasing pressure on coal plants’ bottom dollar.

In the past five years, an average of 2.5GW of coal capacity has been retired annually, and the pace could pick up. Central Electricity Regulatory Commission’s (CERC) (Terms and Conditions of Tariff) Regulations, 2019, allow the beneficiary (distribution licensee) a right of first refusal to allow termination of power purchase agreements (PPAs) with coal-fired power plants at the end of a 25-year period.

In January 2022, the Appellate Tribunal for Electricity upheld the judgment of the CERC relating to the termination of a PPA older than 25 years between BSES Rajdhani Power Limited (distribution company) and NTPC’s Dadri-I thermal power station. CERC’s judgment is likely to accelerate the retirement of old coal plants because it sets a precedent for other distribution companies (discoms) to exit end-of-tenure thermal PPAs.

India has 42GW of coal power plants aged 25 years or older, and another 23GW turning 25 between now and 2032. That means about 65GW potentially reaching retirement age over the next decade. And these plants will have to contend with discoms refusing to extend PPAs.

In IEEFA’s view, India’s coal capacity expansion will possibly be limited to net 20GW, totalling ~230GW by the end of the decade.

Way Forward

India’s net-zero commitment by 2070 will require the achievement of near-term goals starting with the 2030 renewables target. Large corporates and industries are also looking to reduce their carbon footprint and increasingly opting for corporate renewable PPAs. Further, the government is looking to decarbonise other emission-intensive and hard-to-abate sectors which will increase the demand for renewable power.

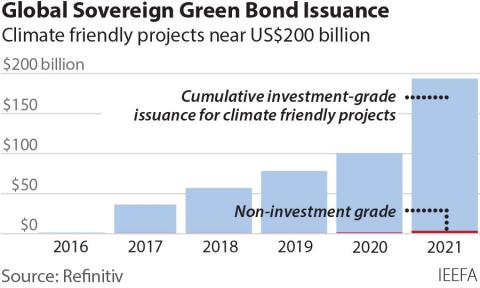

Financing will be a key challenge for building these large assets.

Indian renewable energy developers have gained access to foreign equity and debt capital. But a larger pool of ESG and sustainability-linked funds is available, such as through government-backed sovereign green bonds. For dollar-denominated green bonds, the currency risk adds to cost capital.

The Indian renewables financing market also needs access to domestic capital. There is a scope to raise domestic capital through rupee-denominated green bonds to expand the pool of financing for renewables.

This article first appeared in the Economic Times.