The Energy Department's hydrogen gamble: Putting the cart before the horse

It’s a problem of timing. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is about to make decisions on whether to fund methane-based hydrogen hubs, when it does not yet know whether such hubs will be clean enough to qualify—reliably and over the long term—for the grant of funding. Charging ahead without that knowledge is putting the cart before the horse.

The federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Act of 2021, Section 40314, authorizes the DOE to invest billions of dollars to commercialize technologies that strengthen U.S. energy independence and cut carbon emissions. The statute allocates $8 billion for building regional clean hydrogen hubs. These hubs are not experimental pilot projects (funding for which is established in another section of the law), but rather infrastructure development projects to establish jobs-generating, hydrogen-based industrial centers. The program is designed to encourage hydrogen production not only from electrolysis of water, but also from chemical processing of methane from natural gas—if the carbon emissions can be captured efficiently enough to qualify the project as “clean.”

The DOE has encouraged 33 entities to submit full applications for funding. The agency has not disclosed their identities. Resources for the Future, however, has compiled a preliminary list based on voluntary public announcements made by 22 of the applicants. The information it has compiled indicates:

- Only five of the 22 announced pre-applicants plan to produce hydrogen solely using renewable energy and water (11 include renewable power but also involve fossil fuel or nuclear energy).

- Eight plan to rely either entirely or partly on nuclear power and water.

- Nine pre-applicants propose either entirely or partly fossil fuel-based hydrogen production.

This preliminary information suggests a substantial amount of the regional clean hydrogen hub funding may go to bolster the extraction, transport, and use of fossil fuels, primarily natural gas.

When methane (rather than water) is used as the feedstock for hydrogen production, the methane molecule—which is comprised of one carbon atom and four hydrogen atoms—must be broken up to free the hydrogen atoms to form hydrogen gas molecules (H2). The problem is dealing with the carbon gas that remains.

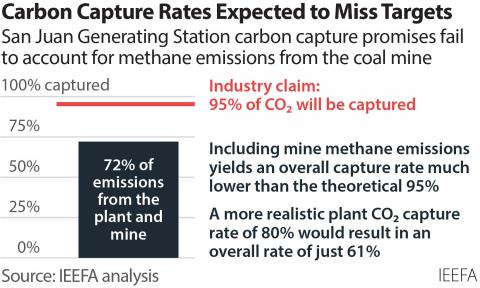

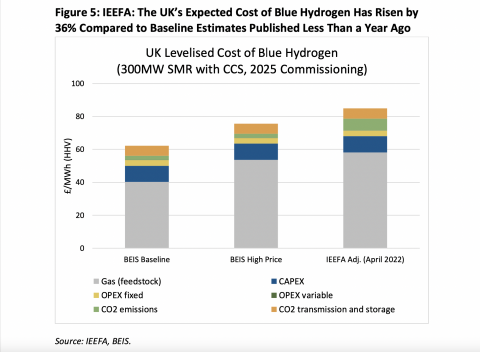

The DOE asserts methane-based hydrogen can meet the “clean hydrogen” requirement through the use of technology to capture the remaining carbon gas and sequester it, and that a methane-based hydrogen project that achieves a 95 percent carbon capture rate will be sufficiently “clean” to qualify for the federal funding.

Here's where the timing issue arises. The application deadline for funding to build the hubs is April 7. The DOE has stated it expects to make decisions on the first phase of funding for six to 10 hubs by the end of the year.

But IEEFA’s research reveals that no carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) system has so far achieved a consistent 95 percent annual average carbon capture rate on a commercial scale over the long-term.

Applications for new carbon capture demonstration funding, some of which may be relevant to hydrogen hubs, have already been submitted, and selections are expected by March 31, with grants awarded by Aug. 31. Although the CCS decisions will be made slightly earlier than the hydrogen hub decisions, the results of the carbon capture projects will come years too late to justify any selections of blue hydrogen projects under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act.

CCS equipment malfunctions or operational problems can have a significant impact on carbon emissions. For example, Petra Nova, a large carbon capture project into which the DOE sank $165 million, experienced substantial down time. Over its three years of operation at a coal-fired power plant, it captured a substantially lower amount of carbon than anticipated. Emissions data reported to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) suggests the Petra Nova CCS project’s actual annual average CO2 capture rate may have been as low as 65 percent to 75 percent, rather than its touted target of 90 percent or higher.

One of the two existing commercial hydrogen production facilities with CCS, the Air Products hydrogen plant in Port Arthur, Texas, reported to the EPA that testing proved the carbon capture rate could exceed its goal of 75 percent, based on a 2013 capacity test. During a 2014-2017 DOE demonstration period, however, the facility captured an average of less than 50 percent of the CO2 generated by the hydrogen production process.

The other commercial hydrogen production facility with CCS, the Quest project in Alberta, Canada, started out with an 83 percent annual capture rate, but the rate declined in efficiency in subsequent years. By its fifth year of operation, the average capture rate for the Quest project was reported as 78.2 percent. The carbon capture system, however, had one full month of downtime, suggesting an actual annual average capture rate of 71.7 percent, minus a few other days of reduced or halted carbon removal. The operators reported the steam methane reformer burner performance was degraded by flame instability when the carbon capture system operated at higher capture rates.

The reported capture rate for both hydrogen projects also only applies to the stream of emissions from the hydrogen production process, not the power used to run the carbon capture equipment or to compress the captured carbon gas for transport in pipelines. Including those emissions sources reduces the carbon capture rate for onsite emissions.

In addition, the CCS rate calculations above didn’t consider downstream emissions of carbon or upstream emissions of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas.

The bottom line is that claims of CCS system efficiency are not reliable unless the technology has been operating for a period long enough to establish a meaningful track record of successful carbon capture rates over the longer term. That will not happen by the time the DOE plans to make its hydrogen hub funding decisions.

Instead, the DOE will allocate initial funding grants without knowing if the carbon capture rate claims made in the fossil fuel-based hydrogen hub applications will actually be achieved.

Not all hydrogen hub funds will be released immediately. The DOE plans to allocate the funding in four phases. Phase 1 covers initial planning and analysis to ensure the technological and financial viability of the hub concept. Phase 2 will finalize engineering designs, business development, permitting and other project launching details. Phase 3 will launch construction and installation activities. Phase 4 will cover commencement of full operations and operational data collection.

The problem is, the question to be addressed in Phase 1 cannot be answered in the near future with regard to fossil fuel-based hydrogen.

The DOE has said it may issue a second opportunity to solicit more hydrogen hub applications. It should delay funding of methane-based hydrogen hubs until more reliable evidence is developed that the hubs can remove enough carbon to meet the definition of a regional clean hydrogen hub.

The size of the money pot is big, but so is the challenge. The DOE should not gamble with taxpayer money, especially when water-based “green hydrogen” production—which does not involve the drilling, transport and use of a fossil fuel that emits greenhouse gas pollution or require the use of unproven carbon capture technology—is a potential alternative.