Delays of LNG terminals in the Philippines reflect supply and cost uncertainties

Two advanced liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects in the Philippines recently delayed commercial operations to next year, due partly to challenging dynamics in international LNG markets.

The terminals, led by First Gen and Singapore-headquartered Atlantic Gulf & Pacific (AG&P), are now aiming to begin operations in the first quarter of 2023.

However, these new timelines are overly optimistic. In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, global LNG supply is constrained and prices have hit record highs. These problems are unlikely to be resolved by early 2023. In fact, LNG industry players are anticipating that the ongoing supply crunch may not ease until 2026.

This means that even if terminals are brought online next year, the Philippines may grapple with supply uncertainty and high prices for years to come.

LNG is unlikely to ease high power costs

The Philippines is turning to LNG imports to compensate for declining production from the Malampaya gas field, the country’s only source of indigenous gas. Malampaya is expected to run dry by the mid-2020s, adding urgency to the development of LNG infrastructure.

Natural gas currently provides 25% of power generation to the Luzon grid, with negligible gas usage in non-power sectors. Estimates range from two to five million tons of LNG per year to continue running the country’s five existing gas-fired power plants.

However, the total capacity of proposed LNG projects far exceeds what is needed. Projects with a combined capacity of 36.5 million tons per year are at various stages of development, along with 29.9 gigawatts of additional gas-fired power projects.

With such a large pipeline of proposed LNG projects, the Philippines risks becoming significantly exposed to the extreme volatility of global LNG markets. IEEFA has previously flagged the risk that unaffordable prices could cause LNG facilities in emerging markets to go underutilized.

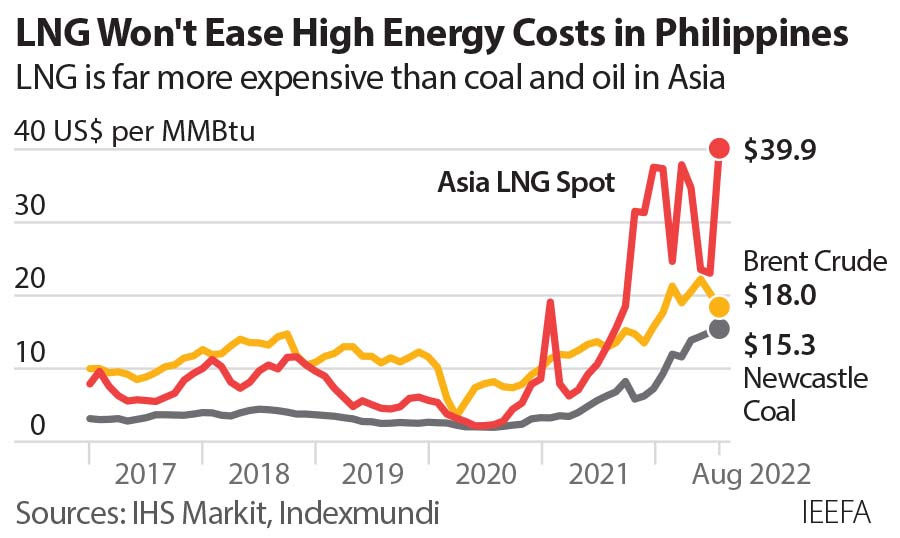

In winter 2021, prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, prices in Asia were around US$35 per million British thermal unit (MMBtu) — 10 times the average price in 2020. Following the invasion, LNG prices in Asia spiked to US$84.76/MMBtu. Prices have since settled to US$45/MMBtu but remain out of reach for many developing economies.

For perspective, compare the high costs of imported coal to current LNG prices. The Philippines’ high dependence on imported coal is one of the key reasons that power prices are among the highest in the region. Coal prices are now around US$430/ton, 100% higher than this time last year.

LNG prices are even higher. The cost of LNG is roughly three times the current price of coal a per-unit of energy basis.

This means that a transition from one volatile, expensive import fuel (coal) to another (LNG) is unlikely to reduce power bills for Filipino end-users. Due to the structure of power supply contracts in the Philippines, international fuel costs are passed through to consumers’ utility bills.

Since fossil fuel companies in the Philippines do not typically bear the cost of higher fuel prices, they have little incentive to slow LNG expansion and promote cheaper forms of energy.

LNG volatility is cause for skepticism and caution

Some may argue that LNG prices will soon settle to affordable levels, but prices are widely expected to remain elevated for the next four to five years. European buyers have aimed to substitute Russian piped gas with non-Russian LNG supplies, putting them in direct competition with Asian LNG importers and driving up prices.

With only modest new LNG supply capacity coming online until about 2026, the bidding war for available LNG volumes may continue to buoy prices. Industry representatives and other LNG importers have warned of a prolonged crisis.

LNG executives in the Philippines have also argued that while one-off spot market purchases of LNG may be expensive, long-term contracts offer cheaper prices.

But according to several sources, the Philippines has not yet signed any long-term contracts for LNG supplies. And given tightness in the global market, contracts with existing LNG supply facilities are challenging to come by. Portfolio sellers currently have little incentive to sign term contracts given sky-high prices and potential profits in spot markets.

Unless companies in the Philippines have already secured access to low-cost LNG, they may be forced to shell out exorbitant sums — on the order of US$145 million per shipment — for LNG supplies.

LNG expansion in the Philippines should be viewed with intense skepticism and caution. Although pitched as a reliable, affordable “bridge fuel” to transition from coal, LNG is inherently volatile and expensive. This is true especially when compared to the declining costs of domestically-sourced renewable energy technologies, which do not require recurring fuel payments.

As such, the transition to renewable energy sources — not the replacement of one imported coal for LNG — offers the greatest potential for reducing household electricity bills and boosting economic growth in the Philippines.