Building credibility in Indonesia’s energy transition: Insights from the ETM and JETP Indonesia

Download Briefing Note

Key Findings

Indonesia’s energy transition obligations are legally embedded through the Paris Agreement and its ratification in 2016. However, the country remains one of the largest carbon emitters in Asia, and coal-fired power continues to dominate its electricity generation.

The international community has coordinated resources through the Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM), launched by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the Just Energy Transition Partnership for Indonesia (JETPI) to accelerate renewable energy development and expedite the shutdown of coal-fired power plants (CFPPs).

JETPI and ETM face legal, institutional, and financial challenges. Limited financing, ambiguous legal frameworks, and insufficient involvement of domestic institutions constrain the programs’ potential, reducing credibility and domestic resonance among investors and national stakeholders.

Indonesia’s taxonomy adopts permissive definitions, allows continued CFPP financing, and lacks precise end dates for transitional activities. This risks confusing investors, complicating joint funding, and making it harder to align with global sustainability standards.

Indonesia is one of the largest carbon emitters in Asia, producing 1.57 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions in 2023. As a signatory to the Paris Agreement, the country committed to reducing emissions, with its energy transition obligations legally embedded through its ratification in 2016 (Law No. 16).

In October 2025, Indonesia submitted its Second Nationally Determined Contribution (SNDC), reiterating its pledge to achieve net zero emissions by 2060 or earlier. Under a scenario compatible with 1.5°C goals, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are likely to peak in 2030 at 1,244 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e), then decline, reaching 540 MtCO2e in 2050.

Currently, the energy sector accounts for 49% of Indonesia’s carbon emissions, with coal-fired power as the largest source. Coal alone accounts for 68% of total electricity generation. The country’s energy transition will require a reduction in coal (fossil-fueled power) and an increase in renewable-generated power. The Government of Indonesia (GOI) has issued Presidential Regulation No. 112 of 2022 (PR 112 of 2022) and the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) Regulation No. 10 of 2025 on the Roadmap for Energy Transition in the Electricity Sector (MEMR 10 of 2025), which aim to accelerate renewable energy development and expedite the shutdown of coal-fired power plants (CFPPs).

Two mechanisms to blend in international partnerships and assistance

To support Indonesia in its mitigation efforts, which would also deliver global benefits, international organizations and institutions have coordinated resources through two programs. These are the Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM), launched by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) for Indonesia, initiated in November 2022 in collaboration with the International Partners Group (IPG).

Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM)

The ETM was launched in 2021 by the ADB as a platform for using a blend of concessional and commercial capital (blended finance) to accelerate the retirement of CFPPs and their replacement with clean energy. The ETM began with three pilot countries, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, and was later extended to Kazakhstan.

The ADB has supported the ETM for Indonesia under the Climate Investment Funds Accelerating Coal Transition (CIF-ACT) program, which received in-principle approval to access USD500 million of concessional, risk-bearing capital in October 2022. The program intends to accelerate the retirement of up to 2 gigawatts (GW) of CFPP capacity by 5–10 years, thereby reducing up to 50 MtCO2e by 2030 and 160 MtCO2e by 2040.

In November 2022, the ADB and other partners signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Cirebon Electric Power, an independent power producer (IPP), to explore the early retirement of the first CFPP under the ETM program. The planned transaction aimed to retire a 660-megawatt (MW) coal power plant in Western Java, and establish a model that could be replicated across other Indonesian CFPPs.

Just Energy Transition Partnership for Indonesia (JETPI)

The Just Energy Transition Partnership for Indonesia (JETPI) was launched by the GOI and a group of countries under the aegis of IPG in November 2022 on the sidelines of the Group of 20 (G20) Summit in Bali. This followed the pioneering JETP agreement for South African CFPP retirement in November 2021. Under the JETPI, the IPG member countries provide public funding through bilateral development programs, supported by multilateral development banks (MDBs), philanthropies, and climate funds. Private sector funding is coordinated through the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), with a JETP working group of seven global investment banks representing 675 private sector financiers.

The JETPI aims to achieve peak power sector emissions of no more than 250 MtCO2e by 2030, a 44% share of renewable energy generation by 2030, and net zero emissions in the power sector by 2050. Under this scenario, early CFPP retirements totaling 1.7GW are to be carried out by 2040, supported by the ETM.

To achieve this, the JETPI envisages an investment plan costing USD97.1 billion between 2023 and 2030, and up to USD580.3 billion between 2023 and 2050. An initial commitment of USD20 billion, half of which is from IPG’s public funds, is expected to serve as a further catalyst, covering approximately one-fifth of the 2023–2030 needs.

The status of the programs, three years on

The JETPI and the ETM agreements were passed three and four years ago, respectively. Subsequent developments highlight the practical challenges of navigating conflicting interests and making decisions. They also offer insights on what is required to translate ambitious transition frameworks into actionable projects.

Progress on the ETM has stalled, despite years of negotiations and technical discussions between the GOI and relevant stakeholders. Towards the end of 2025, three years after the MoU was signed, the GOI announced that the Cirebon-1 CFPP retirement plan had been canceled. This development revealed the institutional, legal, and financial barriers that need to be addressed before large-scale coal retirements can be realized. In the future, insights from this experience will be critical in refining Indonesia’s approach and ensuring that future ETM projects are better aligned with national priorities, investor expectations, and the broader goals of a just energy transition.

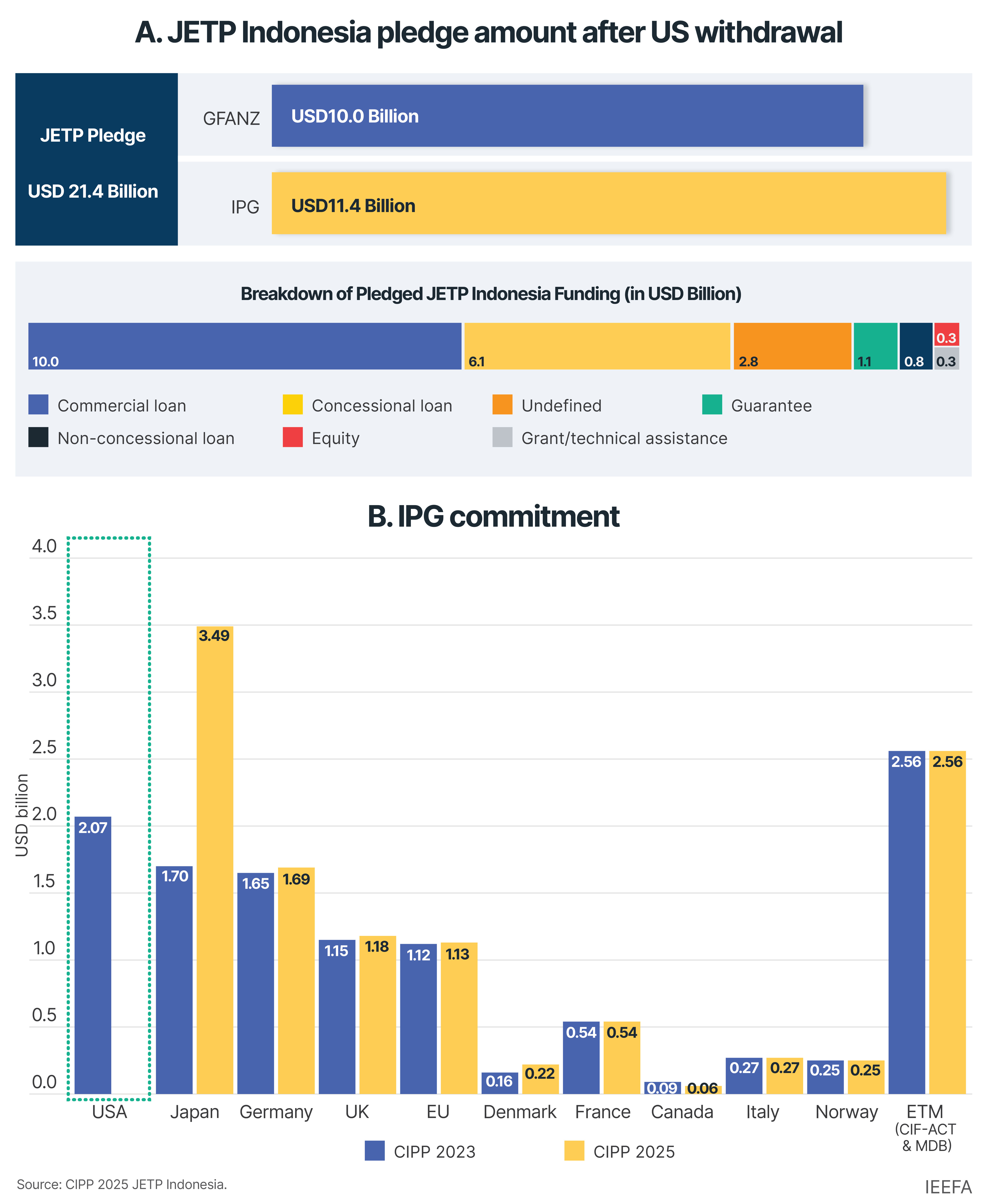

Contrastingly, the JETPI initially successfully established an institutional and financial architecture. However, shifting political dynamics soon posed challenges. In early 2025, the United States (US) withdrew from all JETP partnerships, including the one with Indonesia. Other partners held firm, and Germany has subsequently assumed the role of co-lead. IPG and GFANZ members reaffirmed their commitment, raising the funding pledge to USD21.4 billion by September 2025 to replace the US commitment.

Figure 1: JETP Indonesia funds commitment

Despite the pledged financing, JETPI’s progress has been slow. Of the USD21.4 billion committed, only about USD3.1 billion has been approved (14.5% of the total), covering five programs worth USD870 million, four projects amounting to USD2 billion, and 44 grants totaling USD206.6 million.

The early narrative on JETPI has focused too narrowly on emissions reduction and coal retirement, without consistently linking these efforts to Indonesia’s broader national priorities, such as job creation, industrial growth, and energy security. A more holistic framing would better highlight how decarbonization efforts can enable economic development. The absence of such a narrative has limited domestic resonance and political traction.

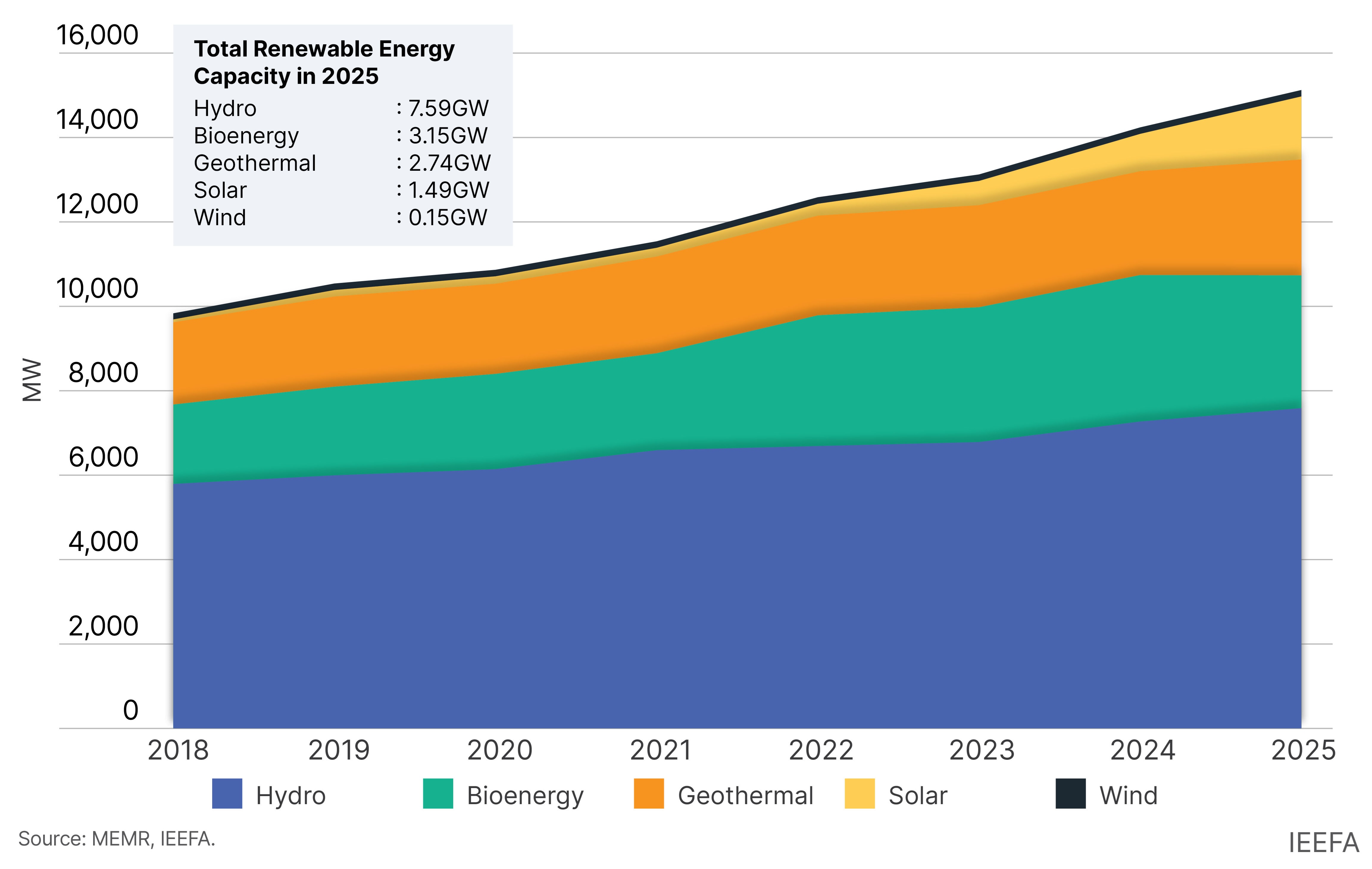

This constrained progress is reflected in the continued dominance of fossil fuels in Indonesia’s energy mix. As of December 2025, renewable energy contributed just 15.75% to overall generation, with hydroelectric, biomass, and geothermal sources comprising the bulk of this capacity (13.5GW out of a renewables total of 15.6GW). Although the government revised its renewable energy target, lowering the 23% goal for 2025 to a more flexible 19–23% range by 2030 under the 2025 National Energy Policy, the gap between current performance and future ambition remains substantial. Achieving even the lower 19% target will require accelerated investment, stronger policy enforcement, and a more sustained effort to diversify away from conventional fossil-based generation.

Figure 2: Indonesia’s renewable energy capacity, 2018–2025

Strengthening Indonesia’s Just Energy Transition Partnership

The JETPI and ETM represent pioneering innovative approaches for accelerating the early retirement of coal plants. Several critical issues have surfaced, and addressing them decisively will help expedite Indonesia’s energy transition.

The need for a robust legal framework, effective coordination, and streamlined execution

The success of ambitious mechanisms, such as the JETPI and ETM, depends crucially on institutional support, with the government playing a key role through transparent and consistent policies. To date, PR 112 of 2022 and MEMR 10 of 2025 are the only legal bases for JETP, ETM, and CFPP retirement. However, with a single overarching Presidential Regulation, the legal framework is insufficiently developed and may not withstand the legal challenges likely to arise. A well-structured and comprehensive legislative framework is needed to provide a robustlegal foundation for JETP.

Additionally, existing power purchase agreements (PPAs) legally bind CFPPs to deliver power, making amendments difficult without the consent of all parties. As Indonesia’s CFPP fleet is relatively young, there are often significant outstanding loans taken out to finance them, which adds complications through lenders’ interests.

Equally important is effective communication, coordination, and policymaking across the diverse institutions involved. A mechanism that involves multiple parties, such as the IPG, requires careful design and sustained effort. The JETP comprises several institutions and organizations with diverse stakeholders, including international governments, national ministries, state-owned and private corporations, and civil society organizations. Communication and coordination strategies are still being formalized and need further enhancement, with the JETPI serving as a mediator among different institutions.

Finally, the scale of Indonesia’s renewable energy development targets under the JETP plan requires streamlined execution. Project timelines should be accelerated, and procurement processes simplified and standardized. Without such reforms, the risk of delays and inefficiencies will undermine the credibility of the transition.

Significantly increased financing is required

The amount of funding finalized has been insufficient so far. The committed JETP funding, initially at USD20 billion and later increased to USD21.4 billion, falls far short of what is needed to finance Indonesia's energy transition efforts. Even within that, the grant funding (USD295 million) is a mere 2.6% of the IPG’s USD11.4 billion pledge.

Grants are crucial for financing preparations for the early development of high-risk renewable energy projects, including environmental and topographical checks, feasibility studies, reskilling for workers and vulnerable groups affected by the program, and various just energy transition risk mitigation programs.

Better utilization of national expertise in managing infrastructure projects

The national infrastructure financing company, PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur (SMI), has been positioned as a key facilitator of blended finance and a partner in the JETP process. SMI is also the country platform manager of the ETM. Its publicly stated goal to enhance climate financing promises increased coordination between the ETM’s international and domestic parties, and for unlocking higher funding. Similarly, the Indonesia Infrastructure Guarantee Fund (IIGF) is another state-owned enterprise that benefits from higher ratings and de-risks projects or lowers borrowing costs by offering guarantees and insurance to investors and lenders.

Such financial institutions, with local knowledge and expertise, can play a key role in transferring knowledge from MDBs and commercial banks on transition finance. SMI is also a regional leader in the issuance of a green bond. In collaboration with institutions such as the European Investment Bank and Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) of Germany, SMI can also guide other domestic financial institutions in raising and channelling funds through green and sustainable debt frameworks, and in accessing blended finance and climate finance facilities as a government-mandated entity.

In practice, SMI’s activities have primarily focused on general infrastructure rather than on climate finance and CFPP closures. Beyond investments in a geothermal and a hydropower project, publicly available information provides limited evidence of the catalytic role originally envisaged for SMI. Similarly, the IIGF continues to focus primarily on traditional infrastructure, such as roads, and appears underutilized in supporting JETP, ETM, and coal retirement funding, for example, by issuing securities intended to facilitate the transition or through enhanced credit guarantees to lower funding costs.

The necessity of an enabling environment

Quasi-legal regulations and financial regulatory requirements can also play a key role in developing a monetary system that incentivizes the transition and penalizes noncompliant agencies. Taxonomies, which enable stakeholders to classify economic activity using environmental parameters, are a crucial element of this system. Led by the European Union (EU), many countries have developed “green” taxonomies to help financial institutions identify such projects and attract funding.

Since Southeast Asia is reliant on coal as its primary energy source, regional policymakers developed the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance. Several regional countries have used this as a template, especially to enable financing for transitional activities, such as time-bound phaseouts of coal-fired power.

The ASEAN taxonomy mostly excludes coal from green classifications, but it does allow financing for phaseouts or shutdowns of existing CFPPs. Under this framework, Tier 1 is the Green category, while the Amber category has two tiers, Tier 2 and Tier 3. Specifications for Tier 2 are more stringent than for Tier 3. Tier 3 is likely to reach sunset (be phased out) by 2030, while Tier 2 will sunset in 2040.

The Indonesian taxonomy, though based on the ASEAN framework, has used more permissive definitions, which risks undermining its credibility. It does not set an end date for transitional activities and instead states that Tier 3 activities must meet certain emissions criteria by 2030 to continue.

There is also a provision that allows new CFPPs to be financed if they are established as captive generators for processing minerals considered critical to the energy transition. Beyond the broad flexibility this definition provides, permitting CFPPs to qualify for green financing contrasts sharply with global trends and could complicate funding through joint mechanisms. Rather than facilitating transition funding by following internationally accepted norms, the taxonomy risks creating confusion among investors and financiers. It also makes it harder to align with sustainability standards established by other countries and regions.

Conclusion

While negative news has dominated recently, the overall JETPI framework remains functional, though some projects may be scaled back. It is encouraging that the remaining IPG partners have reaffirmed their commitment following the withdrawal of the US. As the JETPI moves into its next, more granular phase, all participants need to refocus on flagship deals, including early retirements of specific coal plants and grid projects, and on navigating the complex negotiations regarding compensation, tariffs, and risk sharing. These deals can then serve as templates for system-wide efforts covering multiple CFPPs.

Indonesia’s overall strategy is well-designed in parts, particularly in detailing how the transition will be financed and engaging both the IPG and international funders, including private and multilateral players. However, grant funding remains limited, constraining the JETPI’s impact. Equally important, legal support is still ambiguous and fragile. Domestic financial institutions, which are integral to the JETPI’s institutional architecture, seem to have been underutilized despite their potential catalytic role. Domestic and political considerations have also left gaps, which could affect how international institutional investors view the program’s credibility.

To strengthen the JETPI and ETM, Indonesia should:

- Establish a comprehensive legal framework that provides clarity and certainty for the implementation of the JETPI and ETM

- Enhance institutional coordination mechanisms to ensure that diverse stakeholders are aligned under a transparent and consistent governance structure

- Mobilize greater sources of concessional and grant funding, with clear allocations for pre-feasibility and other project preparation activities, retraining, and just transition safeguards

- Empower domestic financial institutions to expand their remit beyond traditional infrastructure and become central players in the transition finance framework

- Align Indonesia's taxonomy with international norms, including establishing a clear timeline for transition activities, and eliminating loopholes that allow new CFPPs to qualify for green financing

The credibility of Indonesia's energy transition depends on bold reforms in these areas. If implemented with urgency and clarity, JETPI and ETM can evolve from a promising framework into a transformative mechanism, positioning Indonesia as a regional leader in implementing a just and sustainable energy transition.

This briefing note is based on a book chapter first published in Financing Climate Action.