Australian coal miners should think carefully about what they do with their inflated cash balances

Key Findings

Fossil fuel producers across the globe are reporting super profits on the back of the global fossil fuel crisis, but the high coal prices that have driven that profit will also drive the energy transition away from coal even faster.

Australian coal producers are repaying debts, returning funds to shareholders and some are now poised to balance these actions with capital spending on mine capacity expansions or acquisitions.

However, although prices may remain elevated in the short to medium term, prices will eventually normalise and costs are increasing, margins will be squeezed, mines could become lossmaking again.

While diversified miners begin to shift focus from coal to new energy metals, pure play coal miners should forget capacity expansions, responsibly manage down existing operations, avoid debt, ensure rehabilitation provisions are adequate and return cash to shareholders.

Australian coal miners have recently reported huge profits and cash flows off the back of the war in Ukraine.

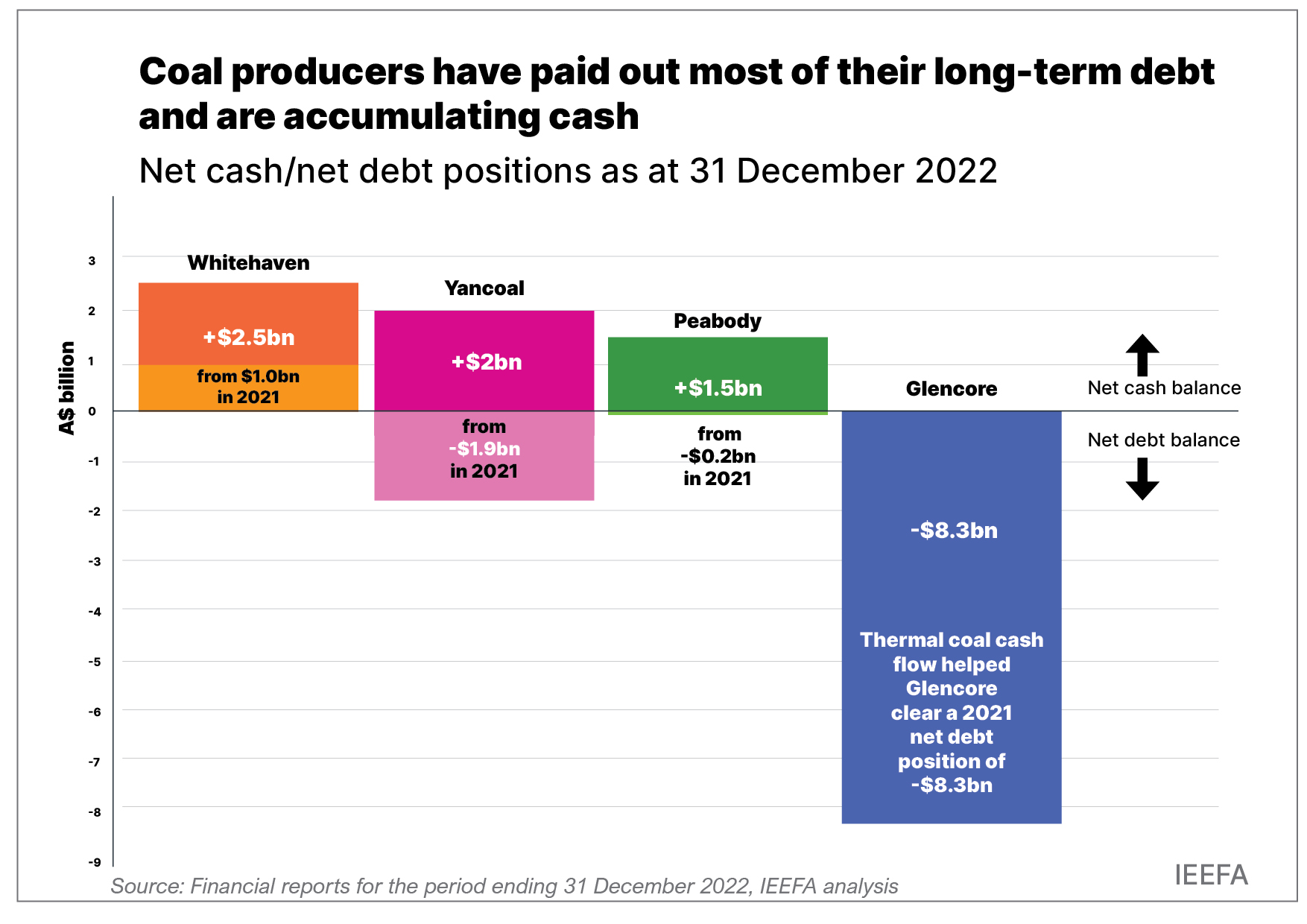

Miners have used these strong cash flows to pay off debt, build healthy balance sheets and are generally returning excess funds to shareholders. Some are also considering capacity expansions or mine acquisitions, including Whitehaven and Yancoal.

Coal prices have now declined substantially while miners have reported significantly higher costs.

However, coal prices have now declined substantially while miners have reported significantly higher costs. On top of this, the global fossil fuel crisis caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine will only accelerate the transition away from coal.

A key question now is what will Australian coal miners do with their bulging cash balances?

Miners’ capital allocation frameworks guide where the company should plough the profits. In 2022 reporting, we can see this demonstrated in maintenance capital, strong balance sheets, expansion plans and returns to shareholders.

Maintenance capital or ‘stay-in-business capital’ such as for mining fleet renewal and continuation of mining footprint has been strong in 2022. Glencore Thermal Australia division spent US$547 million and Yancoal A$548 million to sustain their operations.

A majority of coal producers have now paid out most of their long-term debt and are sitting on huge cash piles. In 2022, miners generally reversed a net-debt position to be net cash positive.

In addition, coal mining owners of coal export terminal Newcastle Coal Infrastructure Group (NCIG) are now paying down the port debt at a faster rate to reduce refinancing risk as lenders increasingly shift away from coal.

Following a period of relative quiet, coal producers are considering expansion alternatives. Whitehaven referenced Vickery expansion in its half-year result. BHP’s listing of Daunia and Blackwater mines for sale has spurred interest for acquisition by other miners.

Finally, record dividend payments to shareholders and share buybacks have featured in 2022. Yancoal has announced A$1.62 billion in total dividends for 2022, Whitehaven announced a A$274 million interim dividend which comes on top of hundreds of millions in share buybacks, and Glencore announced US$5.6 billion in dividends and a new US$1.5 billion share buyback.

The record cash flows put coal miners’ complaints about royalty changes in Queensland and a domestic coal reservation in New South Wales into context. BHP has suggested that the royalty changes are behind its move to sell to Queensland coking coal mines, although it is presumably hoping that potential buyers have a rather different opinion.

Meanwhile, Fitch Ratings has concluded that the NSW Coal Reservation Scheme will have only a limited cash flow impact on coal miners.

Record coal prices a double-edged sword for miners

Coal miners considering opening up new capacity would do well to reset their long-term strategy.

Coal miners considering opening up new capacity would do well to reset their long-term strategy.

The wisdom in opening up new thermal coal capacity in a market set for even faster decline looks increasingly questionable. It’s becoming increasingly clear that so-called growth markets can’t replace declining demand for coal in Australia’s three key thermal coal export destinations – Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

At this stage of the energy transition, high coal prices are a double-edged sword for miners, driving huge short-term profits but destroying long-term demand even faster.

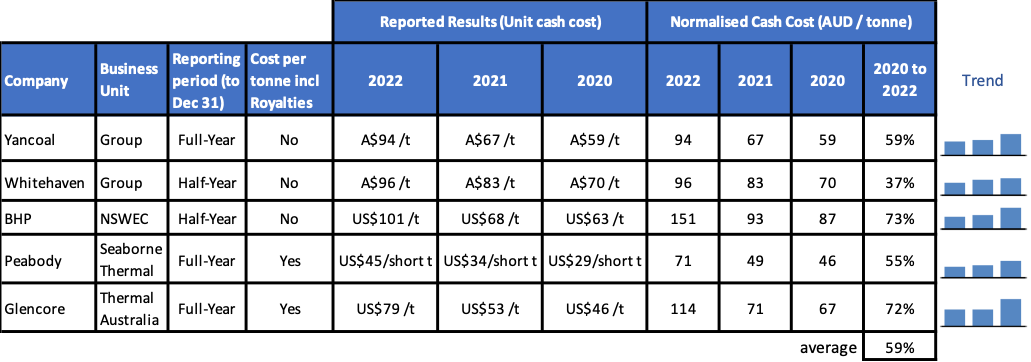

In addition, coal miners have been faced with steeply higher costs. Increases of some 50% in coal cost per tonne are reported from 2020 levels.

Costs are being impacted by inflationary pressures such as higher diesel and explosives prices and higher selling costs such as port fees and royalties, and by labour shortages in the industry, adding pressure to labour costs. Unit costs on lower volumes are also impacted in 2022 by widespread flooding in eastern Australia.

Source: Financial reports for the period ending 31 December 2022 and comparable prior periods, IEEFA analysis.

While some price-reflective costs such as royalty payments should come down as coal prices return to normal, other cost increases are now baked-in. Shippers for one of the Newcastle coal terminals, NCIG, have agreed to accelerate debt amortisation from the original term of 2045 to 2030. Whitehaven reported that this has added A$4/tonne to unit costs. Meanwhile, Yancoal acknowledged that the “cost inflation from recent years is now embedded”. Some cost pressures like labour and the impact of a more volatile climate are starting to look like long-term trends.

Higher unit costs will become more visible when thermal coal prices retreat. Prices are likely to remain somewhat elevated in the short term but could drop below the cost of production in the medium to long term. KPMG’s most recent coal price forecast consensus indicates a long-term thermal coal price of US$90 per tonne. Fitch Ratings recently flagged that thermal coal miners’ rising unit costs together with weakening thermal coal prices may narrow margins.

Miners should also reconsider assumptions about the longevity of their existing operations.

In its 2022 Annual Report, BHP disclosed that a review of its coking coal mine lives resulted in it recognising that the end of its operations “may be earlier than previously anticipated”. This led to an increase in rehabilitation provision of approximately US$750 million.

Thermal coal producers are particularly exposed to earlier-than-anticipated mine closure, due to the structural decline of thermal coal in the global energy transition. Mine closure plans should be regularly reviewed – including capturing current trends in unit cost inflation and the impacts of climate change. Given the increased severity of intense weather events such as flooding, as predicted by the CSIRO and others, mine closure plans should be stress-tested to account for climate change. What was considered an appropriate closure requirement in historical mining approvals may be insufficient in today’s environment.

A 2020 survey of mining leaders – developed in conjunction with consultants SRK Consulting and Turner and Townsend — indicated that in Australia, if leaders felt that climate change would change closure requirements, only 12% felt that miners and regulators were prepared for those changes. It also confirmed (84% of respondents) that adequate capital for closure was set aside only half the time.

The NSW state government should also take the opportunity to test their assumptions. NSW holds just A$3.3 billion in environmental bonds, compared with A$12.3 billion held by the Queensland state government. In February 2023, a report by Hunter Renewal tabled that over the next 20 years, 17 mine closures are scheduled to deliver over 130,000 hectares of mine-owned land to new uses in the NSW Hunter Valley alone.

A more responsible way forward

How long will the good times last? Strong cash flow outlooks for 2023 have been signalled by Australian miners. However, they face high levels of uncertainty with prices now declining, costs rising and long-term demand likely to fall even faster.

Diversified miners have made it clear that they are increasingly focused on mining the new energy metals and minerals that will be in greater demand going forward as renewables increasingly take over from fossil fuels. South32 will no longer develop new coal mines and will wind down its coal operations as current mines deplete.

However, Australian pure-play coal miners have shown little intention of diversifying away from coal. Continued mining capacity expansions look increasingly like the wrong pathway considering the transition away from coal will now happen even faster.

Instead, with balance sheets suddenly much healthier, such miners should refocus on managing down existing capacity, keeping debt low, progressively rehabilitating depleted mines, reviewing mine-closure provisions, and returning excess cash to shareholders.

This article was first published in Renew Economy.