We’ve just published a report that explores what we believe are unacceptably high risks and costs of the Indian government’s proposal to build 12 new nuclear reactors.

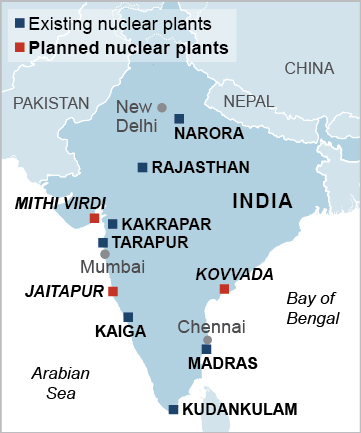

Our study, “Bad Choice: The Risks, Costs and Viability of Proposed U.S. Nuclear Reactors in India,” finds the plan, which would put six reactors each at Kovvada and Mithi Virdi, to be fraught with financial and operational hazard.

FIRST, TO THE KOVVADA PROJECT, WHICH INVOLVES A NEW, UNTESTED ESBWR REACTOR DESIGN from General Electric-Hitachi that has never been operated at a commercial nuclear plant and is not under construction anywhere else.

The history of such untested first-of-a-kind reactors shows that they typically cost far more and take far longer to build than expected and that they experience unanticipated problems both during construction and when they begin commercial operations.

Recent experiences in the U.S. and Europe with building new reactors with untested designs illustrates the typical difficulties:

- The estimated cost of the four new design Westinghouse A1000 reactors under construction in the U.S. has increased by more than 20 percent since construction began three years ago, and the reactors’ estimated in-service dates have slipped by about three years. Additional cost increases and schedule delays at these projects are likely, if not certain.

- Even more striking is that the estimated costs of building the new design European Pressurized Reactors (EPRs), in Finland and France have more than tripled since construction began. The scheduled completion of the plant in Finland has slipped by nine years, from 2009 to 2018, while the scheduled opening of the EPR in France has slipped by six years.

Our first conclusion on the Kovvada project is that it will be very expensive to build and that the first units probably will not produce electricity for the grid before 2031. That’s even if construction begins early next year, which is unlikely given that land acquisition has not started, a contract has not been signed, and GE has said it does not want to invest in nuclear in India unless it is protected against liability for nuclear accidents.

Additionally, we’ve concluded that unless the Indian government provides very large and long-term subsidies, the tariffs for electricity from Kovvada will be very high, with first-year tariffs in the range of 19.80 to 32.77 rupees per kilowatt hour (a conservative estimate by our measure). This is some five to nine times the current cost of generating power in India.

Our third finding on Kovvada is that the total investment to build the project will be massive, somewhere between 4 lahk crore rupees to 6.8 lahk crore rupees, which converts to $60 to $100 billion. This range could be even higher given the uncertainty associated with the project’s status and the problems that are typical of first-of-their-kind plants. It is questionable as to whether the Indian government will be able to finance such a project (along with the one at Mithi Virdi) while continuing to pursue its current investments in coal mines, coal-rail freight, renewable resources and energy efficiency.

Our fourth finding on Kovvada is that it brings substantial operational risk because there is no operating experience with an ESBWR nuclear plant. There is no evidence as to how well the reactors at Kovvada will operate, how much they will cost to run, and how much power they actually will generate. All of these unknowns will affect the tariffs for the electricity from Kovvada.

THE MITHI VIRDI PROJECT POSES SIMILAR RISKS TO RATEPAYERS AND TAXPAYERS, as it also would involve the construction of six reactors using a design that is not in operation anywhere in the world and that has experienced significant construction cost increases and schedule delays where it is being built in the U.S. and in China.

For reasons similar to those outlined above on Kovvada, the Mithi Virdi project —using the untried Westinghouse A1000 design—will prove very expensive to build, and its first unit probably will not produce electricity for the grid before 2029. That’s even if construction begins early next year, which is unlikely, given that land acquisition has not started and a contract has not been signed.

Our second finding on Mithi Virdi is that unless the Indian government provides very large and long-term subsidies, its electricity will be very expensive, with first- year tariffs in the range of 11.18 to 22.12 rupees per kilowatt hour (a conservative estimate, again, by our measure). This would be some three to five times higher than the current cost of generating power in India.

Our third finding on Mithi Virdi: Its construction will cost somewhere between 2.4 lahk crore rupees to 4.5 lahk crore rupees, or $34 to $68 billion dollars, and could be much more, for the same reasons noted above on Kovvada.

Our additional findings on Mithi Virdi mirror those on Kovvada around the India’s government ability to finance the project the operational risks that are likely to come with first-of-its-kind technology.

OUR RESEARCH OFFERS ADDITIONAL COMMON TAKEAWAYS ON BOTH KOVVADA AND MITHI VIRDI, and a note on solar development in India.

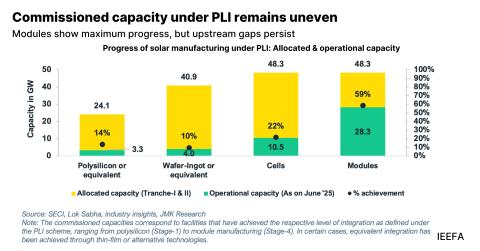

In contrast to the cost of building new reactors, solar tariffs in India have declined by 65 percent just since 2010, and further steep declines are expected in the years ahead. IEEFA sees solar costing less than 3 rupees per kilowatt hour by the time the first units at Mithi Virdi would be online in 2029. As a result, IEEFA puts the tariffs for power from Mithi Virdi at 3 to 6 times higher than long-term fixed-price solar tariffs. Likewise, tariffs for power from Kovvada would be some 5 to 9 times more expensive than solar.

The main conclusion of our report is that neither nuclear power project is economically or financially viable, both would take much longer than expected to build, both would result in higher bills for ratepayers, and both—if they are built—might not work as advertised.

Investing in new solar photovoltaic capacity would be a much lower-cost option, would be significantly less harmful to the environmental, and would be a far more sustainable alternative to Mithi Virdi and Kovvada.

David Schlissel is IEEFA’s director of resource planning analysis.