IEEFA Update: Two Sets of Data Tell the Same Tale: U.S. Coal Industry Continues to Shed Jobs

In a research report we published in January, we explained how the U.S. coal industry will very likely continue its overall decline in a trend that will be accompanied by both employment and market volatility.

A passage from that report (“Short-Term Gains Muted by Prevailing Weaknesses in Fundamentals”):

“Some mine openings and some attendant hirings will be announced in 2017, and these announcements will likely be presented as evidence of a new stability in the U.S. coal industry. They will serve largely to mask the industry’s weak fundamentals, however, as it continues to grapple with the problem of industry shrinkage, a trend that will continue and that IEEFA expects will put this new ‘stability’ at risk.”

Events are bearing out our forecast.

In the first quarter of this year, coal industry jobs declined by 1,266—according to the most detailed of the government’s sets of employment data (more on that below)—after increasing by more than 2,000 in the last quarter of 2016. There is nothing to indicate that jobs recently promised in the U.S. coal industry will be jobs delivered.

In the first quarter of this year, coal industry jobs declined by 1,266—according to the most detailed of the government’s sets of employment data (more on that below)—after increasing by more than 2,000 in the last quarter of 2016. There is nothing to indicate that jobs recently promised in the U.S. coal industry will be jobs delivered.

Indeed, our research suggests mismanagement of a shrinking sector will continue and even stable jobs will remain at risk.

A close look at employment data raises questions but provides clear answers as well. Here’s a rundown:

How many coal-mining jobs are there in the U.S.?

It depends, in a way, on which data repository you consult, although one is much more comprehensive than the other.

Two offices within the United States Department of Labor publish data on coal-mining employment in the U.S.: the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA).

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were 51,000 coal-mining employees in the U.S. in May.

According to the Mine Safety and Health Administration, the average number of employees in coal mining in the U.S. was 73,792 during the first quarter of 2017. The MSHA counts the average number of employees of coal mine operators for the first quarter of 2017 at 52,734. The average number of employees of coal mine contractors during the same period was 21,058.

Why are these two numbers different?

Because the two offices count mine workers differently. The MSHA includes mine workers on mine-operator payrolls and, separately, contract workers. Contract workers are employed by a company other than the mine operator. The BLS does not count contract workers.

The difference is significant because over a quarter of all coal mine employees are contractors.

Another challenge to reading and understanding this data arises because the term “coal miner” includes people who work at the mines but are not coal miners per se. They include truck drivers, mechanics, and office workers who work at the mine and who are counted by both the BLS and MSHA as coal miners.

Why do the two agencies collect data differently?

The Bureau of Labor Statistics, created in the late 1800s, is known for its big-picture figures on employment and unemployment across all sectors of the economy. Two of its most well-known and commonly cited numbers—the U.S. unemployment rate and the change in nonfarm payroll jobs—are released monthly. The agency gets its data primarily through monthly surveys of businesses, government agencies, and individuals. One of those is the national survey of Current Employment Statistics, which asks about 150,000 businesses and agencies about jobs and pay, and then uses this information to estimate how many people are working in hundreds of job categories across the country—including coal mining.

The Mine Safety and Health Administration, an agency created in 1977 to improve safety regulation and enforcement at all types of mines, collects employment data differently. Under the Mine Act, all mine operators are required to file reports about accidents, injuries, employment and production, among other things. MSHA coal mining employment data is much more comprehensive and detailed than the BLS figures.

The two agencies also report on employment at different intervals. The BLS publishes monthly data; the MSHA reports quarterly averages.

What do longer-term trends show?

Here’s where both agencies agree.

Over the past five years, the number of coal-mining jobs in the U.S. has fallen sharply, though it has leveled off and even increased slightly recently.

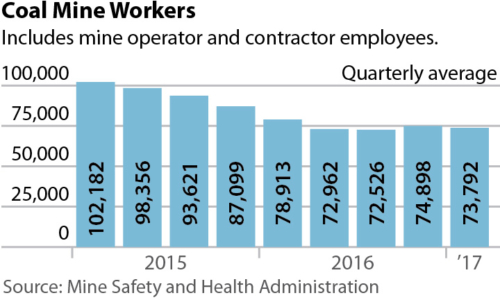

The chart here shows the trend.

The MSHA reports that the average number of workers—those employed by mine operators and those employed by contractors—has declined from about 130,000 in 2012 to fewer than 75,000 very recently.

Both the MSHA and the BLS show jobs attributed directly to mine-operator payrolls declining from about 90,000 in 2012 to about 50,000 very recently.

What do more recent trends show?

Over the course of 2016, the average number of U.S. coal-industry employees, according to MSHA (again, that the agency that publishes the more comprehensive data), was 75,600. That number came in at 78,913 in the first quarter of 2016 before dropping to 72,526 by the end of the third quarter.

It rebounded in the fourth quarter of 2016, from 72,526 on Sept. 30 to 74,898 by year’s end, an increase of 2,372 jobs.

In the first quarter of 2017, however, it dropped to 73,792, a decline of 1,106 jobs.

What’s likely to happen next?

The U.S. coal industry will continue to decline, and it will continue to shed jobs.

This trend will continue to put communities that are reliant on coal-related economic activity in the position of having to manage a difficult transition.

The most successful transition initiatives will identify and implement concrete strategies to promote economic growth, mitigate job losses and ease fiscal stress that will occur when plants and mines are closed.

IEEFA provided just such a blueprint in 2014 for economic transition in response to the closure of the Huntley Plant in Tonawanda, N.Y., and last week proposed a transition plan for communities affected by the impending closures of the Navajo Generating Station and Kayenta mine in Northern Arizona.

U.S. energy markets are changing, regardless of who controls the White House and which party is in power in Congress. The prudent way forward is to acknowledge change now and plan for it immediately.

Seth Feaster is an IEEFA data analyst. Tom Sanzillo is director of finance.