IEEFA update: Accountability for the banks, law firms, accountants and credit agencies that orchestrated Puerto Rico’s $72 billion debt crisis

An army of high-priced talent from some of the world’s most prestigious law firms, accounting companies, investment banks and credit agencies provided the advice and counsel to the Puerto Rican government that paved the way to the commonwealth’s $72 billion debt problem.

The same lawyers, accountants, bankers and credit-rating experts continue to have the ear of the Puerto Rican government.

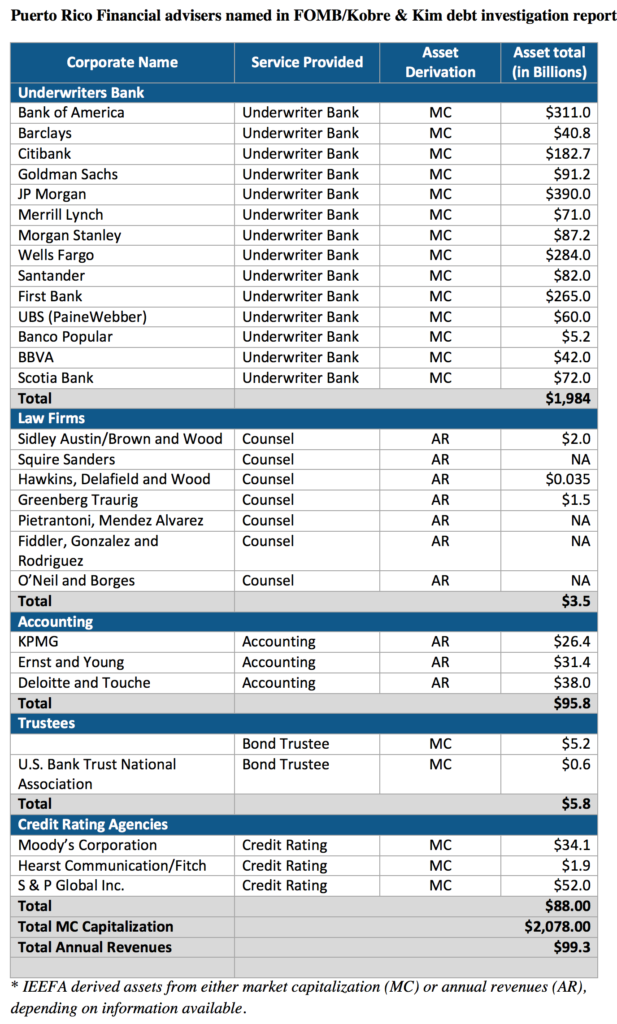

IEEFA estimates that the many advisers in question collectively are worth over $2 trillion by market capitalization (for those firms that are publicly traded) and an additional $100 billion in annual revenue (for those firms that are not publicly traded). This figures come out of our analysis of a recent August report by the Federal Oversight and Management Board (FOMB) for Puerto Rico. The report, issued in August, was prepared for the board by Kobre & Kim, a New York law firm that “focuses exclusively on disputes and investigations involving international fraud and misconduct.”

The report includes more than 600 pages of detail on a myriad of legal claims that Puerto Rico’s bondholders and its government may pursue against these advisers.

But the report has inherent limitations: none of the testimony from 100 witnesses was taken under oath, and although thousands of documents were reviewed, tens of thousands of documents might have been expected given the scope of the problem.

The report is nevertheless a place to start to unravel the tangled web of responsibility for Puerto Rico’s deep financial trouble. Of particular note is its list of companies under contract with various bond issuers who had fiduciary and contractual duties to Puerto Rico issuers. The valuations listed below constitute IEEFA’s analysis of the companies that provided most of the advice. All of them, not incidentally, remain going concerns today—while Puerto Rico in the meantime is bankrupt.

ALTHOUGH THE KOBRE & KIM REPORT LAYS OUT MULTIPLE LEVELS of potential claims, it avoids making any conclusion about the validity of any of them. It points out, for example, that the credit rating agencies involved could defend themselves by asserting that they relied upon what they were told by Puerto Rico’s government and underwriting teams.

Such a defense, like many others offered in the Kobre & Kim report, could prevail. It is a defense that is nevertheless far removed from providing a practical solution for Puerto Rico. That said, the report shows how the credit rating agencies involved ignored a growing body of evidence, failing as far back as 2005 to conduct enhanced due diligence. All maintained Puerto Rico debt at investment grade status until 2014 (see page 285 of the report for detail on that point).

A restitution package that holds advisers who profited from these deals accountable.

In essence, then, the credit rating agencies may well have engaged in actionable misconduct by “assigning higher-than-merited credit ratings to financial institutions that eventually went bankrupt, as well as to securities that carried higher risks of default than the assigned credit ratings indicated.”

These facts warrant further investigation into questions of recklessness and intentional fraud.

URS, the consulting engineer for PREPA—whose job it was to provide the utility with sound management expertise—may on the other hand have a harder time defending its actions. The report is the third review now, after ones by the Puerto Rico Commission for the Comprehensive Audit of the Public Credit and the Puerto Rico Energy Commission, to identify questionable practices by URS. This one says that URS attested to revenue estimates without independent verification and provided the authority with formal statements that the system was in good repair when it was not. URS has recently been absorbed in an acquisition by AECOM, a company with a market cap of $5 billion.

The report is a public service in itself, but one that will be of more value if put to serious use.

Many of the claims laid out need to be developed and put through judicial vetting. Minus such action, it cannot be known with any reasonable accuracy how much of the $72 billion should be paid by Puerto Ricans and how much Puerto Rico’s advisers are responsible for. And this is without even considering the separate question of how much of a debt burden the Puerto Rican economy can bear.

The current process of public wrangling and budgetary gamesmanship over assignment of liability is overlooking a significant potential source of repayment for bondholders.

By establishing a reasonable case for the many claims it describes, the report potentially sets the stage for decades of litigation—a scenario that would be a waste of time and resources. More helpful would be a convening of all parties and the emergence of a common willingness to create a restitution package that holds the advisers accountable.

The appropriate convener would be the Securities and Exchange Commission, although other law enforcement entities like the New York State Attorney General may also have a role to play under the Martin Act, which regulates securities traded in New York. Settlements of the type we envision have occurred elsewhere on a much smaller but no less politically complex level.

What’s called for, in short, is a responsible rendering of liabilities. Those who participated in and profited from the current debt crisis are obliged to fix it.

Tom Sanzillo is IEEFA’s director of finance.

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA op-ed: Who really owes Puerto Rico’s bondholders—and how much?

IEEFA op-ed: Plan to turn to imported natural gas will cost Puerto Rico dearly