IEEFA update: No foreign players will bid in India’s auction of coal blocks

India’s Union government has opened 41 coal blocks for commercial mining under the Aatma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan, a self-reliance program. This measure aims to allow private players to mine coal commercially as part of its effort to cushion the impact of COVID-19.

Tim Buckley, IEEFA’s Director of Energy Finance Studies, Australia/South Asia, discussed the plan with Kundan Pandey of ‘Down to Earth,’ a magazine produced by the Centre for Science and Environment.

Kundan Pandey: What is the current scenario of coal versus renewable energy (RE) in India and across the globe?

Tim Buckley: The world is progressively reducing its reliance on coal for power generation. Most new electricity capacity installations globally are based on renewable energy. The International Energy Agency’s World Investment Outlook 2020 put new coal plants reaching final investment decisions in 2019 at a decade-low of 18 gigawatts (GW) globally, whereas coal plant end-of-life closures globally have been running at 30-35GW annually over 2015-2019.

THE WORLD IS PROBABLY ALREADY AT PEAK COAL POWER PLANT CAPACITY and this will progressively decline each year.

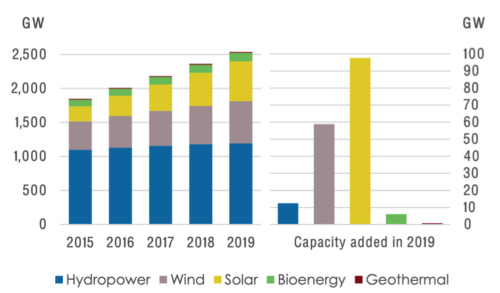

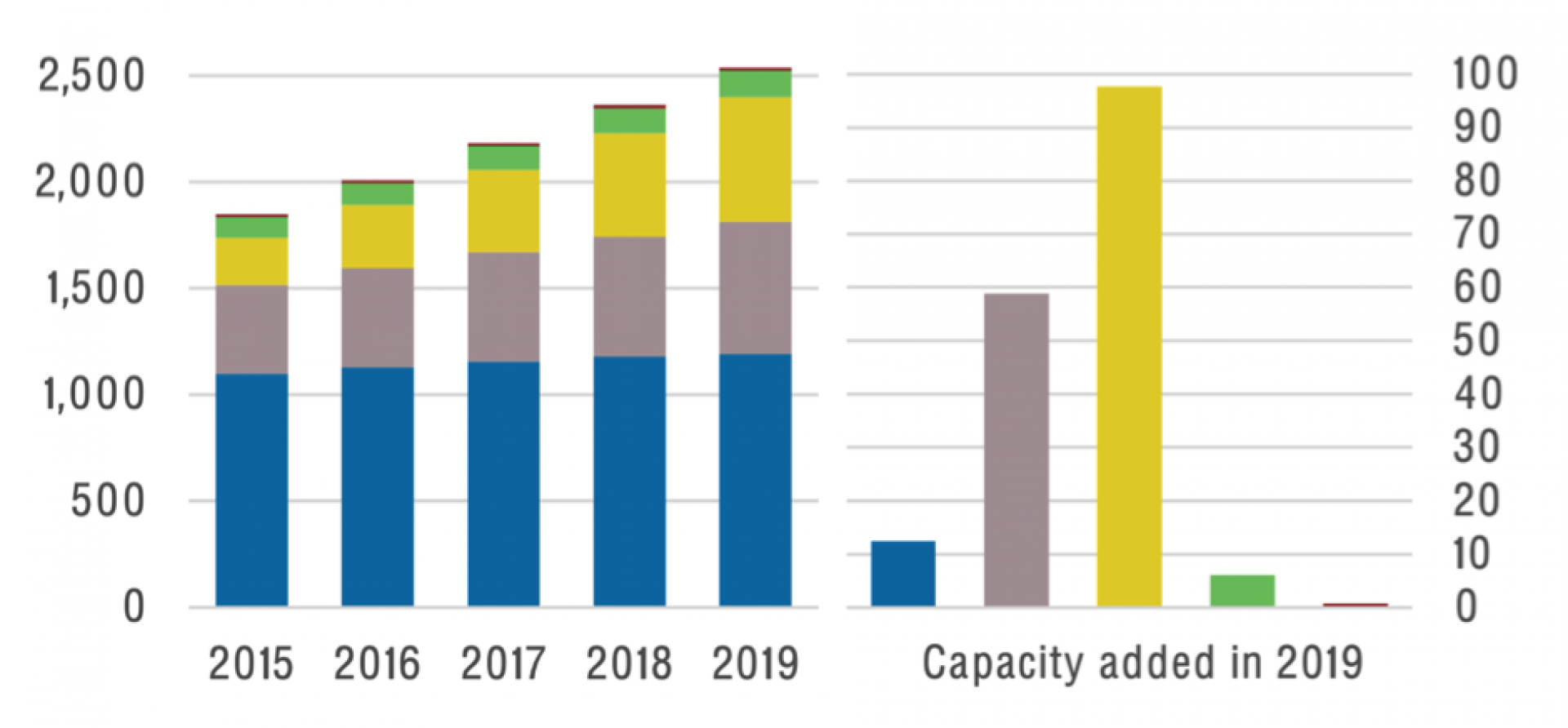

Against that, according to International Renewable Energy Agency, the world added 170-180GW of net renewable energy capacity globally in 2019. The rate of capacity expansion in renewable energy grew in every year of the last decade.

Very few new coal plants are still being built

Coal-fired power plant retirements are accelerating across the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Very few new coal plants are still being built. Among these are the ones that were mostly committed to 5-10 years ago.

The United States will build almost 30GW of renewable energy in 2020 alone, but it does not have a single new coal power plant under construction. In fact, end-of-life coal plant closures will be 5-10GW after a near-record 15GW of coal plant closures in 2019. Coal use in electricity in the U.S. is down 28% year-on-year in the first half of 2020.

For India, the situation is similar. India was commissioning some 20GW annually of net new thermal power capacity over 2012-2016. But over 2017-2020, the rate of net new capacity added dropped by 80% to an annual average of just 4GW.

Figure 1. Renewable Power Capacity Growth (2015-2019)

In the 2019-20 fiscal year, two-thirds of net new capacity added in India was renewable energy (9.4GW) versus 4.3GW of net new thermal capacity.

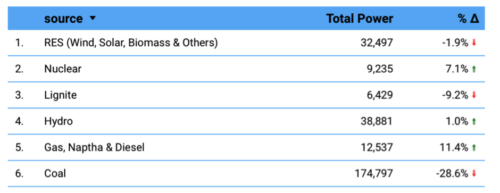

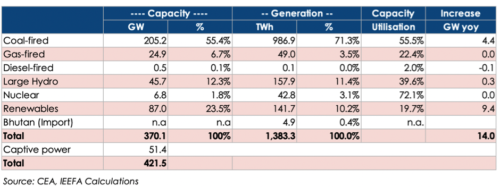

Table 1: India’s Electricity Capacity and Generation 2019-20

To compound the financial distress evident in the coal-fired power generation sector, the average capacity utilisation rate in 2019-20 was a decade-low 55.5%. And year-to-date 2020/21, total electricity generation is down 20.1% year-on-year to 274,402 million units, a drop of 69,000 million units (according to CarbonCopy online data). Within that, coal has suffered a 100% of this decline in demand across India. Coal power generation is down by an annual 28.6% for the year to date. That’s a drop of 70,000 million units.

Table 2: Total Electricity Generation for India (2020-21)

KP: How do you see the Indian government’s decision to auction coal blocks? It becomes pertinent considering the forecast of falling coal prices in Australia and other countries.

TB: The Indian government is desperately keen to address India’s critical energy security issue of excessive reliance on expensive imported fossil fuels. The move to auction these coal blocks to private domestic and foreign interests reflects the Indian government’s objective to progressively reduce imports of coal, which ran at costly 233 million tonnes in 2019/20, up 3.2% year-on-year.

The government has rightly been talking about reducing ‘avoidable coal imports’ to zero by 2023-24. While the logical solution is to accelerate investment in low-cost, domestic-sourced renewable energy, the Indian government is looking at all angles, including bringing more private mining competition to Coal India Ltd.

FROM A SUSTAINABLE ECONOMIC GROWTH PERSPECTIVE, IT DOES NOT MAKE SENSE TO AUCTION COAL BLOCKS, particularly when most of these blocks do not have environmental clearances or clarity in land ownership issues. Many are in heavily forested areas. All these issues will materially dampen investor interest.

KP: Do you think global players will show any interest in Indian coal mines?

TB: IEEFA expects almost no foreign interest in this auction process. For the world to deliver on the Paris Agreement, unabated thermal coal use must cease in the OECD member countries by 2030, in China by 2040, and globally by 2050. Global investors are increasingly acknowledging the climate science is all too accurate and the financial risks of stranded assets are rising rapidly.

IEEFA research has found that 139 globally significant financial institutions across the banking, insurance and asset manager/asset owner sectors have formal coal divestment policies in place. These polices are getting progressively tighter. There were 39 new or enhanced coal divestment policies announced in 2020 to date, almost double the announcement rate seen in 2019. Global capital is fleeing thermal coal mining.

The financial risks of stranded assets are rising rapidly

The Indian press has speculated that BHP Group Ltd, Rio Tinto Corp and/or Peabody Energy would be interested in bidding. I would say this is entirely unlikely; none of these three will bid in my view. Neither will any other global coal firm, most likely. BHP recently put its last Australian thermal coal mine up for sale. The company in 2019 committed to progressively reduce its exposure to thermal coal mining.

RIO TINTO SOLD ITS LAST COAL MINE IN 2018, HAVING PROGRESSIVELY EXITED THE COAL SECTOR since 2014, reflecting the inconsistency of coal mining with the Paris Agreement. Rio Tinto also consistently failed to make adequate financial returns in coal mining, including booking cash losses of $4 billion from one disastrous foray in Mozambique in 2012, which it wrote off and then virtually gave to Coal India Ltd in 2014. Coal India Ltd failed to make the Mozambique operation viable. The chance of Rio Tinto moving back into coal is precisely zero, in IEEFA’s view.

Peabody Energy is in clear financial distress, having destroyed 90% of its shareholder wealth in the last two years alone (refer to chart below). The company is struggling to downsize its U.S. and Australian coal mining businesses, so again the company’s capacity to undertake high risk greenfield developments in India is zero.

Figure 2: Peabody Energy’s Stock Performance Versus the S&P 500 Index Over the Last Two Years

KP: Besides revenue and employment, India is also looking for self-reliance on coal and reducing import bills. Do you think it’s possible considering India’s coal quality is not good enough?

TB: India’s coal quality is very low by global standards, with an average energy content of 3,000-4,000 kilocalories per kilogram and ash content of 20 – 40%. Coal on the seaborne market is 5,000-6,000 kilocalories per kilogram, with an average ash content of 10%.

India’s coal quality is very low by global standards

But coal is coal, and coal-fired power plants can and have been built to burn all sorts. India’s existing 205GW of coal-fired power plant capacity has largely been designed to use India’s low-energy, high-ash coal. Only a few isolated coastal coal power plants, like the one in Mundra, have been configured to use higher-energy, lower-ash imported coal. These can be retrofitted to blend in more Indian coal.

The issue is that many of these 30GW coastal coal-fired power plants are not connected by railway lines to domestic Indian coal. They are generally 1,500 kilometres away, making transportation of domestic coal problematic. It also doubles the cost of the coal on delivery relative to the mine-mouth cost.

KP: Acquiring modern technology was one target when India decided to sell coal blocks to the private sector. Do you think India can achieve this if global players don’t join the bidding process?

TB: India has exceptionally low wages for coal miners. It is entirely sensible for India to modernise its work practices and progressively bring in global coal-mining technologies. However, this progressive automation/modernisation and substitution of labour with capital would have serious consequences for the Indian workforce and would raise the cost of production.

It is entirely feasible for experienced Indian firms to bring in progressively heavier capital equipment to reduce the labour intensity of coal mining in India. But doing so will further undermine the already-tarnished social licence to operate that this destructive, dirty, dangerous and often corrupt industry has.

The question is largely theoretical, given that global coal mining firms are universally in dire financial shape and face an existential threat from increasingly global capital flight to lower-cost, zero-emissions renewable energy alternatives.

This is an excerpt from an interview with Tim Buckley published in Down to Earth.

Related articles:

Modi claims private coal mining to boost India’s energy security

Why are corporate giants pulling out of thermal coal?

IEEFA update: The outlook for thermal coal in Southeast Asia and South Asia

IEEFA update: Who would still fund a new coal power plant in India?