IEEFA update: New Mexico emerges as a proxy for the U.S. electricity sector transition

At a packed open-door hearing in the New Mexico state capital of Santa Fe this week, both sides of the roiling debate over the future of public energy policy weighed in.

At a packed open-door hearing in the New Mexico state capital of Santa Fe this week, both sides of the roiling debate over the future of public energy policy weighed in.

Or rather, all sides: Coal miners, conservationists, tribal activists, renewable energy aficionados, ratepayers, politicians and religious leaders.

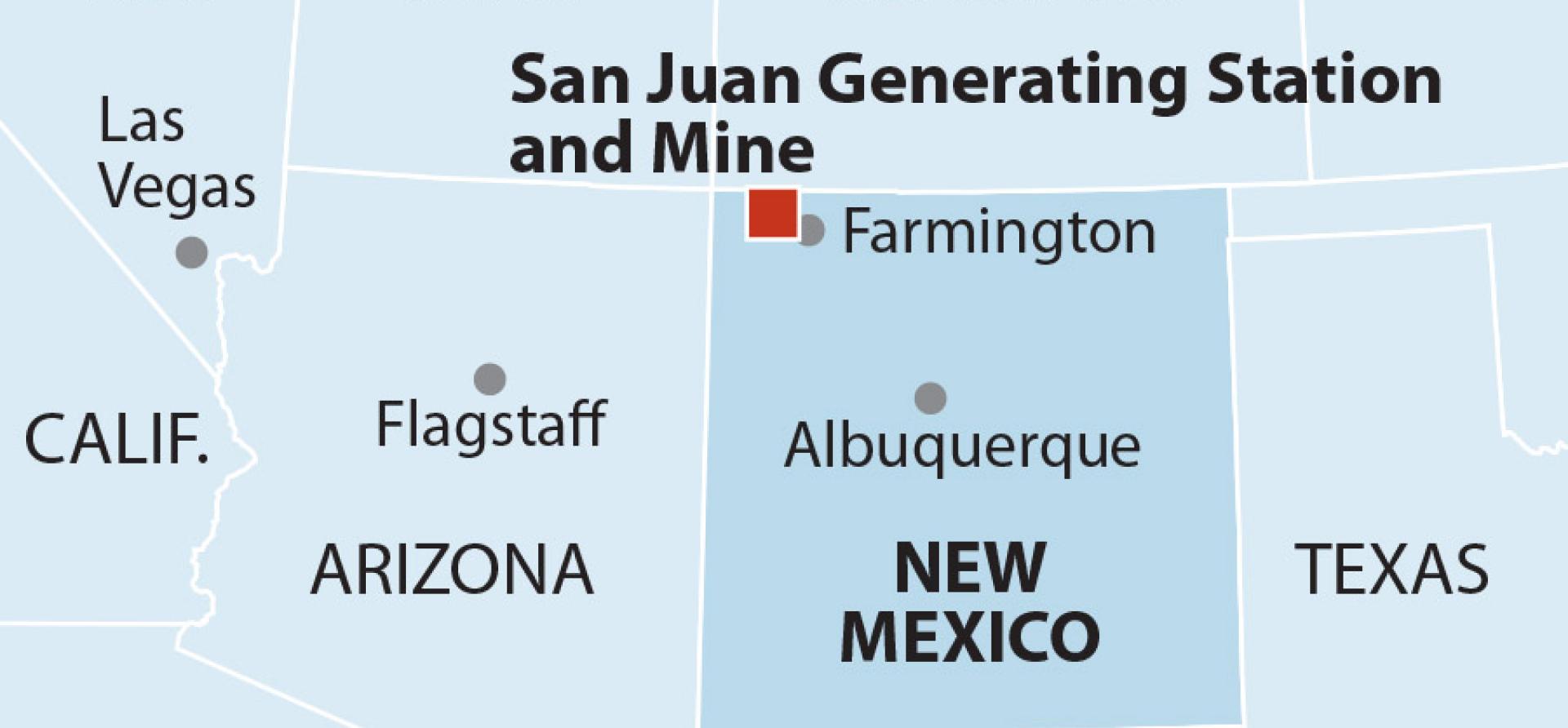

At issue was how—and whether—the state will allow Public Service Company of New Mexico (PNM) by 2022 to close the San Juan Generating Station, an aging coal-fired power plant outside Farmington, NM, the biggest population center in the fabled Four Corners region of the desert Southwest.

PNM, CITING MARKET CHANGES THAT ARE MAKING COAL-FIRED POWER OBSOLETE, WANTS TO SHUTTER THE PLANT and replace it with gas-fired power and utility-scale solar. The PNM proposal is opposed by some who want to keep Farmington’s traditionally coal-dependent economy as is—and by regulators who think the utility is attempting an evasive strategy.

The politics are tangled and the particulars unique. But the debate distills a bigger, national question as to what coalfield economies can do in the face of forces that spell the end of electricity production as it has been conducted for generations. IEEFA published a report this week—Dim Future for Illinois Basin Coal—that describes how communities in southern Illinois, southern Indiana, and western Kentucky—just like Farmington–are rapidly entering the same energy transition, one for which they are largely ill-prepared. A similar story is unfolding in Montana and Wyoming, as detailed in an IEEFA report published in March, Powder River Basin Coal Industry Is in Long-Term Decline.

The details may vary from place to place, but the public comments and concerns that bubbled up before the Public Regulation Commission in Santa Fe could well have been sounded in any coalfield town, anywhere in America.

“You’re simply putting people out on the street and that’s not what you want to do.”

“The crisis isn’t just about climate change,” said a third-generation miner from Farmington who argued that without responsible community reinvestment, “you’re simply putting people out on the street and that’s not what you want to do.”

Part of the local debate is about the Energy Transition Act, an ambitious law enacted this year that puts New Mexico at the forefront nationally of state renewable energy mandates. The ETA, as the law is known, has been criticized for language that would let PNM recover $360 million in closure costs from ratepayers, which state regulators say infringes on their authority. On the other hand, the law has garnered broad public support for the $40 million it would require PNM to reinvest in the Farmington area.

The Rev. Vincent Chavez, an Albuquerque Catholic priest and 16th-generation New Mexican, said regulators would do well to get out of the way and let “the most visionary forward-looking clean energy policy in the country” proceed.

Likewise, Sister Joan Brown, executive director of New Mexico Interfaith Power and Light, said, “I feel we need to act and not get mired in more bureaucracy.”

“PNM HAS MADE THIS DECISION TO LEAVE, AND IT’S GOING TO HAPPEN,” added Joseph Hernandez, an energy-issues organizer for the Native American Voter Alliance.

Every one of the dozens of people who spoke—almost all of whom took full advantage of their allotted three minutes at the microphone—agreed on the urgency of the issues at hand, whether from a local or global perspective.

Meanwhile, a diversion is being sustained by out-of-state operators who have swayed some in Farmington to believe that the San Juan Generating Station can be rejiggered into a money-making carbon-capture project.

IEEFA has reported previously on the extensive problems with that proposal, by a recently incorporated company called Enchant Energy—and by the misguided hype it is creating locally (see our July report, Novice Company’s Carbon Capture Pitch Offers False Hope, Fiscal Risk to Farmington, N.M.).

Enchant Energy’s project to keep the San Juan plant open depends on fantasies

The project stands little chance of success because it depends on financial and technological fantasies, as David Schlissel, IEEFA’s director of energy resources planning analysis, detailed in testimony filed with the New Mexico Public Regulation Commission last month. It will also likely encounter resistance from current utility company owners of the plant who prefer a more responsible way forward—one that takes cleanup liabilities seriously and that can ride the wave of the emerging utility-scale solar industry.

QUESTIONS PERSIST, TOO, AS TO ENCHANT ENERGY’S CAPITALIZATION, ITS EXPERIENCE, and its understanding of the marketplace.

Unfortunately, the chimera being offered up by Enchant is delaying the vital discussion that needs to take place now—by communities, politicians and regulators, among others—on how to ease the transition from coal to more economically-sound forms of power generation.

Karl Cates is an energy transition policy analyst at IEEFA. He lives in Santa Fe.

Related items:

IEEFA update: U.S. carbon-capture project deal is dead on arrival

IEEFA update: High-risk carbon capture deal not in New Mexico city’s best interest

IEEFA New Mexico: Why Acme’s carbon capture plan for San Juan plant won’t work

IEEFA report: ‘Holy Grail’ of carbon capture continues to elude coal industry