IEEFA Op-Ed: Investors Should Steer Clear of the Keystone Pipeline

The oil industry is in trouble, beset by bankruptcies of junior companies, write-downs by major producers, and canceled or drastically delayed projects across the board. The last thing it needs is the proposed Keystone XL pipeline, which President Trump this week moved to resurrect after only five days in office.

The oil industry is in trouble, beset by bankruptcies of junior companies, write-downs by major producers, and canceled or drastically delayed projects across the board. The last thing it needs is the proposed Keystone XL pipeline, which President Trump this week moved to resurrect after only five days in office.

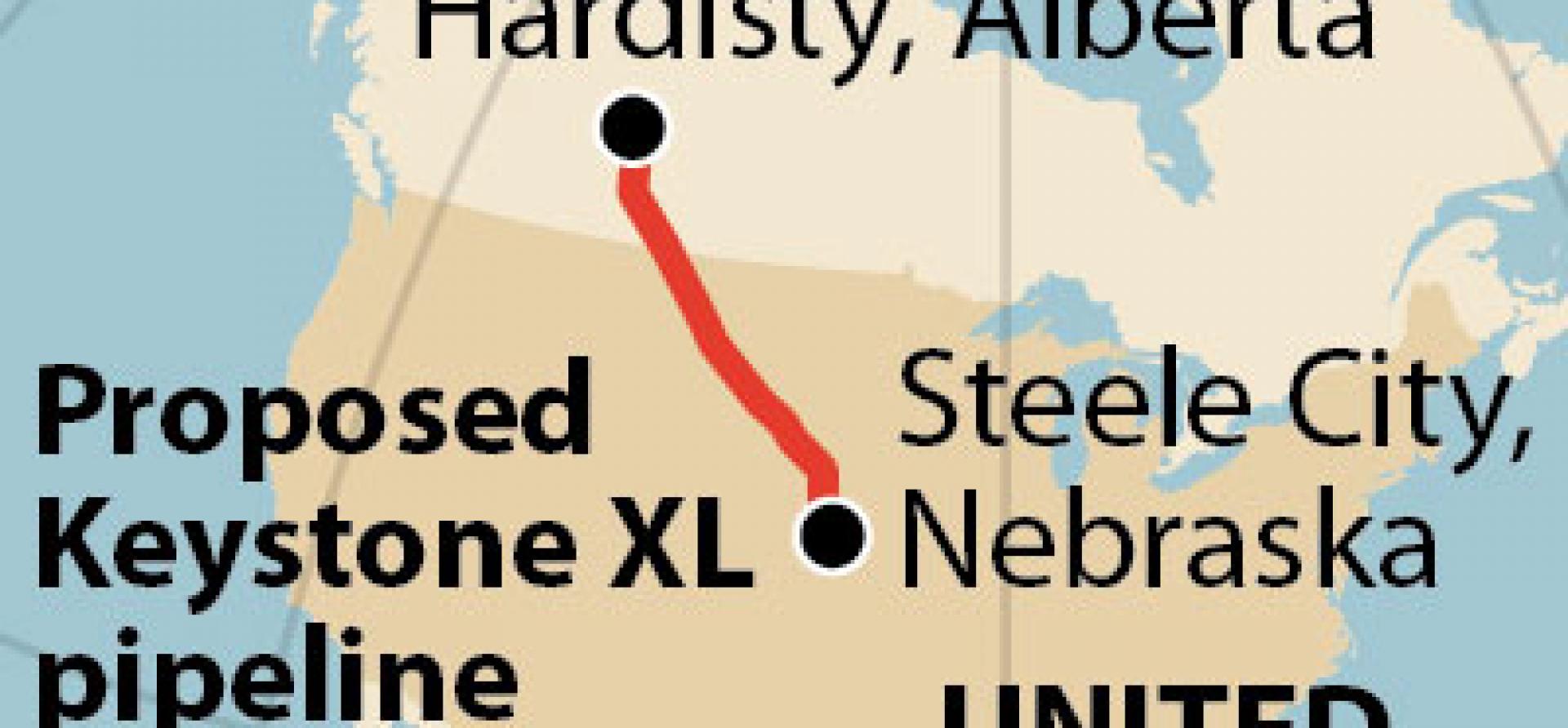

If the president gets the approvals he needs, this would be a reversal of the Obama administration’s efforts to quash construction of the pipeline, which would link oil producers in Canada and North Dakota with refiners and export terminals on the Gulf Coast. Obama, citing environmental reviews, opposed the project, saying it is not adequate given its route through the Sandhills ecosystem in Nebraska.

The pipeline would be supplied mostly by oil sand reserves in Canada, which are too expensive to unlock unless—contrary to all expectations—global oil prices magically regain record heights. Public opposition to the project is so vast as to guarantee interminable litigation and the sort of costly headline civil disobedience that has worked so effectively against completion of the similarly financially rickety Dakota Access Pipeline. Climate policies enacted by international governing bodies pose risks to development of fossil-fuel resources everywhere. Divestment campaigns are gaining momentum. Competition from cheap shale gas and renewables is formidable. Political cohesion among oil-producing nations is tenuous.

THE FUNDAMENTAL REALITY IS THAT CANADIAN OIL SANDS ARE ECONOMICALLY VIABLE ONLY WHEN OIL PRICES RISE TO EXCEPTIONALLY HIGH LEVELS, AND WHEN THEY STAY THERE FOR A LONG TIME.

This makes the reserves that Keystone would purport to tap deeply vulnerable to oil prices, which are notorious for their volatility and neither robust today or likely to take off again in the foreseeable future. The grand-daddy of all oil companies, ExxonMobil, acknowledged as much just a few months ago when it indicated it would write off 4.6 billion barrels of oil-sands reserves in Canada, where it has very little to show after a decade of acquisitions. While prices have rebounded from the high $20-per-barrel range a year ago to the mid-$50-range today, they are far short of the $80 it would take to make oil-sands production profitable.

From a strictly financial point of view—one devoid of political context—the Keystone XL is a singularly poor investment. And while bankruptcy will always be available to its owners and financiers, the losses such a project’s failure would create for communities, employees, small businesses and local governments would be long-lasting.

A more complete assessment of the proposal must of course factor in the politics of the project. Worldwide concern over climate change has put the oil industry squarely in the crosshairs of international agreements and grassroots movements against such projects. One irony of President Trump’s election is that it may only intensify opposition in the U.S.

If the pipeline sponsor, TransCanada, goes forward with its plans, expect an increasingly professional and resourceful coalition to expand among environmentalists, landowners, tribal governments, and local municipalities.

At its core, Keystone is a strangely un-American project that belies the Trump administration’s “America First” slogan. If it were to defy the odds and be built, it would, at best, allow Canada to expand its oil markets at the expense of the U.S.

Squandering riches on superfluous high-risk infrastructure will not generate profits or stimulate economic growth.

Better investment opportunities lie in what Americans truly need and want—more hospitals, better roads, safer transit systems, greater access to education, and cleaner energy.

Tom Sanzillo is IEEFA’s director of finance.

[This column first appeared on Fortune.com]

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Analysis: The Economic Frailties and Rickety Finances Behind the Dakota Access Pipeline

IEEFA Analysis: Investment Bank Blindness to Risk in Fossil-Fuel Sector

IEEFA Update: Renewable Energy, Gone Mainstream, Is a Rising Tide