IEEFA Europe: Will Germany Walk the Walk on New EU Emissions Rules or Just Talk the Talk?

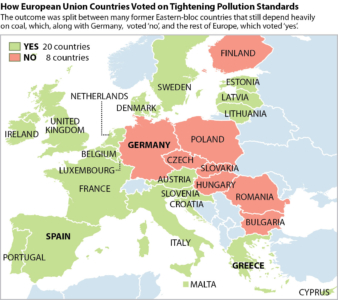

By recently opposing stiffer new European pollutions limits for coal-fired power, Germany—an avowed leader on progressive climate-change policy—joined the ranks of the most reluctant nations, most notably Poland.

At issue actually are two major sources of carbon emissions—coal and lignite—lignite being a lower-grade, and dirtier, cousin of coal. Both produce air pollutants such as oxides of nitrogen and sulphur (NOX and SOX).

Germany favors its lignite industry for complex socio-economic reasons. It provides jobs for miners and utility dividends for local municipalities, plus cheap power generation. So two weeks ago, Berlin stood in opposition to the new emission rules with Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Finland. In the end, the new limits—called the revised BREF—were still approved, by a wafer-thin EU majority.

The revised BREF is to be implemented starting in 2021.

GERMANY’S OPPOSITION REINFORCES AN APPARENT CONTRADICTION BETWEEN THE COUNTRY’S GENEROUS SUPPORT FOR RENEWABLE POWER AND ITS FAILURE TO CURB LIGNITE, the most carbon-emitting form of power generation.

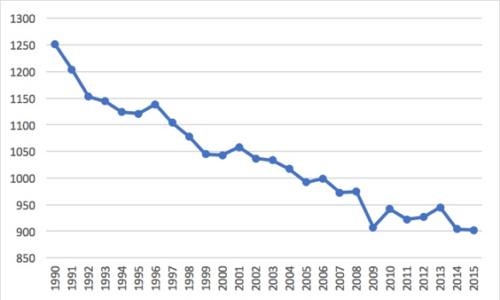

Germany’s annual carbon emissions have been flat since 2009, after steady reductions over the previous two decades (Figure 1 below). And the country’s lignite consumption has been flat for more than decade. Official estimates put consumption in 2015 at 1.6 million terajoules, the same as in 2005. Meanwhile the country spends €10 to €11 billion annually on solar power.

An IEEFA analysis of European Environment Agency NOX emissions data helps illustrate why Germany opposed the revised BREF limits. The analysis is part of a report we published last week, “Europe’s Coal-Fired Power Plants: Rough Times Ahead.”

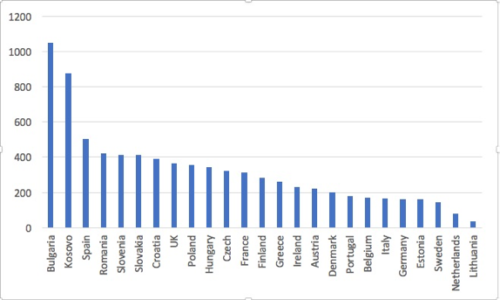

Average NOX emissions across Germany’s biggest coal, lignite and biomass power plants were 162 mg/Nm3 in 2014, according to our calculations. That already meets the new, revised BREF limit of 175 mg/Nm3 (from 2021). And it’s far below the European Union average of 279 mg (see Figure 2).

But dig a little deeper, and you find that German lignite power plants are higher, on average, at 181 mg, versus 158 mg for coal (see Table 1).

And if you examine lignite power plants by capacity—as we did—you find that the size bracket with the most power plants, 1050-2050 MWth, is also the most polluting, at 204 mg.

The fact that these power plants are closer to the BREF limit than many others in Europe will have rubbed salt into the wounds inflicted by the new rules, given that only a slightly higher limit (say, 190-200mg, as Germany was arguing for) would let Germany off the hook.

WILL GERMANY NOW WALK THE WALK OR JUST CONTINUE TO TALK THE TALK—will it embrace BREF or try to obstruct it?

Berlin could try to obstruct BREF by arguing that the cost of meeting the revised limits would exceeds the benefit, given that its power plants are already so close to the limit.

Conversely, Germany could apply the revised limits rigorously through policies that would require definitively stricter permits starting in 2021. Such a move could have larger beneficial ripples, contributing toward a more coordinated and coherent strategy to meet stretching carbon emissions targets in 2020 and 2030, and reducing air pollution.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the German lignite operator, LEAG, which is owned by the Czech Republic-based EPH, sees German politicians as being in a position of having the last word on BREF implementation. Their hope is probably for continued opposition.

Responding to the IEEFA report, LEAG put out this spin:

“The decision adopted in Brussels opens up scope for political choices. The Federal Government has not yet consented to the BREF-LCP in its entirety and has a right of objection. We are committed to ensuring that the Brussels decisions are properly and correctly implemented. The intended emission bandwidths for nitric oxide and mercury are derived from a technical base and do not correspond to the current state of the best available technology.”

Utilities and politicians will have to respond quickly to BREF because adopting a wait-and-see (or wait-and-lobby) approach may not work. The BREF vote itself showed that the momentum is toward clean-up rather than delay. And as we said in our report, delay carries risk. Utilities that wait too long will have to absorb higher compliance costs as a bottleneck for power plant upgrades develops.

Figure 1. German annual greenhouse gas emissions, 1990-2015, mln tonnes

Figure 2. Average NOX emissions rate across coal/ lignite/ biomass burning installations, EU member states

IEEFA calculations, based on EEA data

Table 1. NOX emissions by coal and lignite in Germany, 2014

| Size of power plant | Total lignite capacity | Lignite, average NOX emissions | Coal, average NOX emissions |

| MW thermal | MW thermal | mg/Nm3 | mg/Nm3 |

| 50-1050 | 7,183 | 167 | 156 |

| 1050-2050 | 18,634 | 204 | 167 |

| 2050-3050 | 7,983 | 178 | 152 |

| 3050-4050 | 3,703 | 188 | 163 |

| 4050-5050 | 9,158 | 147 | 112 |

| 6050-7050 | 11,574 | 186 | 165 |

| All | 58,235 | 181 | 158 |

IEEFA calculations, based on EEA data

Gerard Wynn is an IEEFA energy finance consultant.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Europe: Offshore Wind Costs Maintain Falling Trend

IEEFA Update: A Rush to Subsidies as Power Plants in Europe Face an Existential Threat