Europe achieved its lowest-ever bid for an offshore wind power project last week in a German auction in the North and Baltic Seas, an event that backs up a recent trend of cost reductions.

Germany’s first so-called “reverse auction” for offshore wind shifts away from a feed-in tariff schemes in an approach intended to drive down costs.

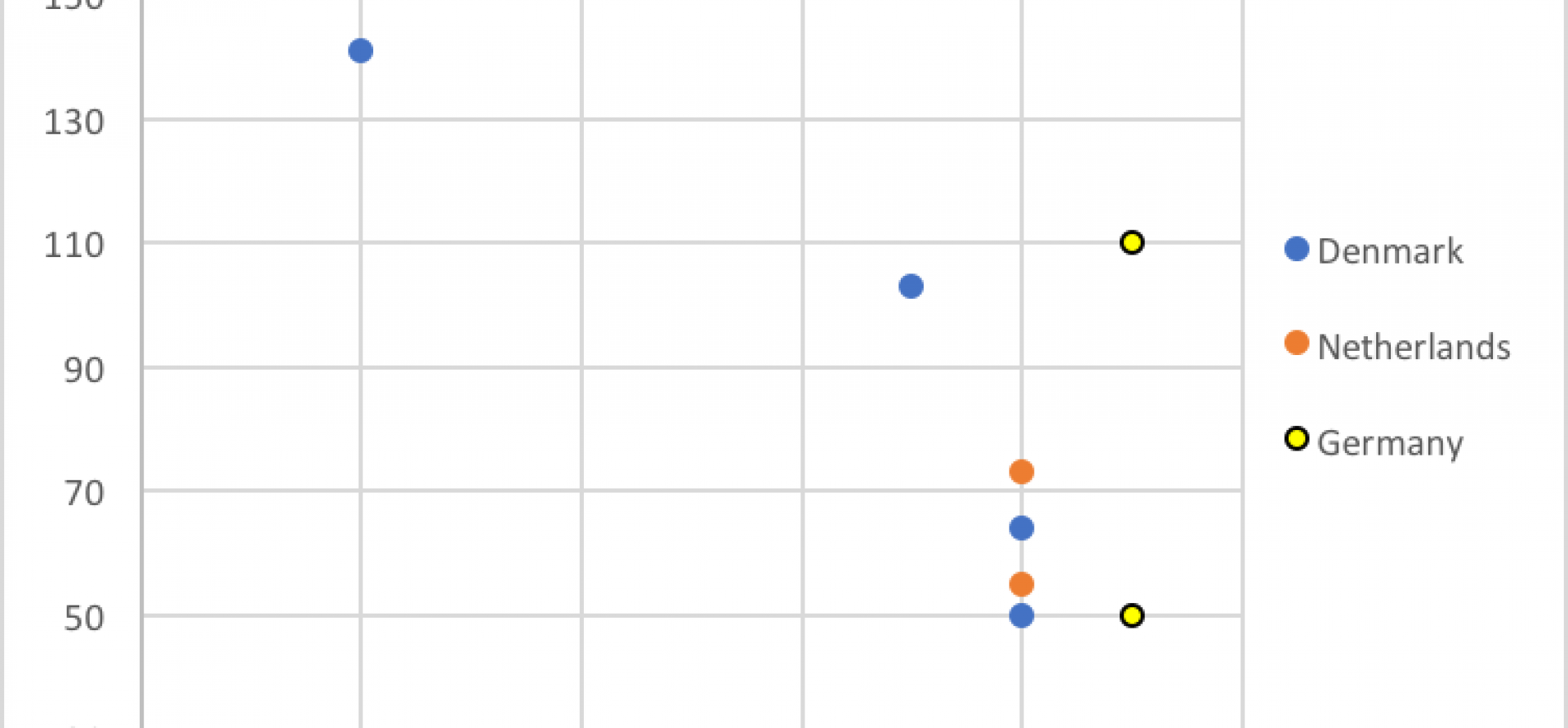

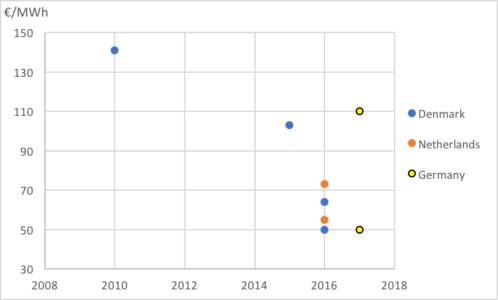

The German auction fetched an average bid of €4.4 per megawatt hour and several bids of zero euros, following a general trend of lower prices in similar auctions in Denmark and the Netherlands.

In Germany, the bids are on top of the wholesale power price. As a result, a bid of zero euros will receive only the wholesale power price.

In Denmark and the Netherlands, bids are an all-in amount, which comprises the wholesale power price, plus a “sliding tariff” that tops up the difference to the bid amount.

In all three countries, successful bidders will receive a free onshore and offshore grid connection and connecting sub-sea cable. So as a result, a bid of zero euros, as in Germany last week, is not exactly unsubsidised.

That said, it’s good to keep in mind that offshore wind projects take a while to build: last week’s German auction was for projects to be completed by 2025 at the latest. The auction revealed the cost of offshore wind not today, but in up to eight years’ time, assuming the project is completed.

Notwithstanding these caveats, costs for offshore wind appear to be falling.

PERHAPS MOST SIGNIFICANTLY, COMPETITIVE AUCTIONS HAVE DRIVEN DOWN THE SUPPORT PRICE DEMANDED BY DEVELOPERS, compared with previous, publicly administered prices under former, fixed feed-in tariff schemes.

In addition, a step-change in turbine sizes has helped, with turbines now about to produce around 8 megawatts up from 3-4 megawatts a few years ago. Meantime, rising investor confidence has driven down costs of capital.

Cost reductions are good news for renewable energy growth in north European countries, where winter peak demand coupled with northern latitudes make solar power a more medium-term prospect.

These regions have access to robust offshore wind resources in the shallows of the North Sea encircled by Britain, Norway and northern continental Europe.

And in a notable advantage over other variable renewables, offshore wind fulfils a much greater proportion of its theoretical nameplate capacity—called load factor—compared with solar and onshore wind power, because the wind at sea blows stronger and more often.

Britain is the world leader in offshore wind deployments, with more than 5 gigawatts installed. In Britain, load factors last year were 37% for offshore wind, versus 24% for onshore wind, and 11% for solar.

Figure 1 below shows the recent cost trend in Denmark, the Netherlands and Germany. Britain is not included, given its regime pricing includes the costs of the offshore grid connection, making direct comparison difficult. In the case of Germany, we include last week’s maximum and minimum bids (€60 and €0 per MWh), and add a hypothetical power price of €50/MWh, reflecting expectations for much higher German power prices in the 2020s.

Figure 1. Bids in offshore wind reverse auctions since 2010, Denmark, Netherlands, Germany

Gerard Wynn is an IEEFA energy finance consultant.

[The third paragraph of this column was corrected to show the recent German offshore auction fetching an average bid of €4.4 per megawatt hour, not €44 per megawatt hour, and the auction drawing several bids of zero euros, not one bid of zero euros.]

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Report: A U.K. Electricity Transformation Under Way, But in Need of Better Direction

IEEFA Europe: Can Power Market Reforms Curb U.K. Ratepayer Handouts to Gas, Coal and Nuclear?