Malaysia’s CIMB announces coal financing phase-out by 2040 as Asia’s fossil fuel divestment drive accelerates

Malaysia’s CIMB Group Holdings (CIMB) has announced a comprehensive coal exit policy with a commitment to phase out both project and general corporate financing of thermal coal mining and coal-fired power generation across its portfolio by 2040.

This is a first in several ways. CIMB is the first Malaysian bank to act on a formal exit policy. It is the first emerging markets bank globally to formalise a progressive coal exit policy. And it is also the first Islamic financial institution to do so. This positions CIMB as a leader on sustainable finance in Southeast Asia, building on its position as the first bank in the region to sign the UN Principles for Responsible Banking.

CIMB is the first Malaysian bank to act on a formal exit policy.

Significantly, CIMB’s policy is also more comprehensive than the coal exit policies announced last year by the three largest banks in neighbouring Singapore – DBS, UOB and OCBC – as it includes corporate finance.

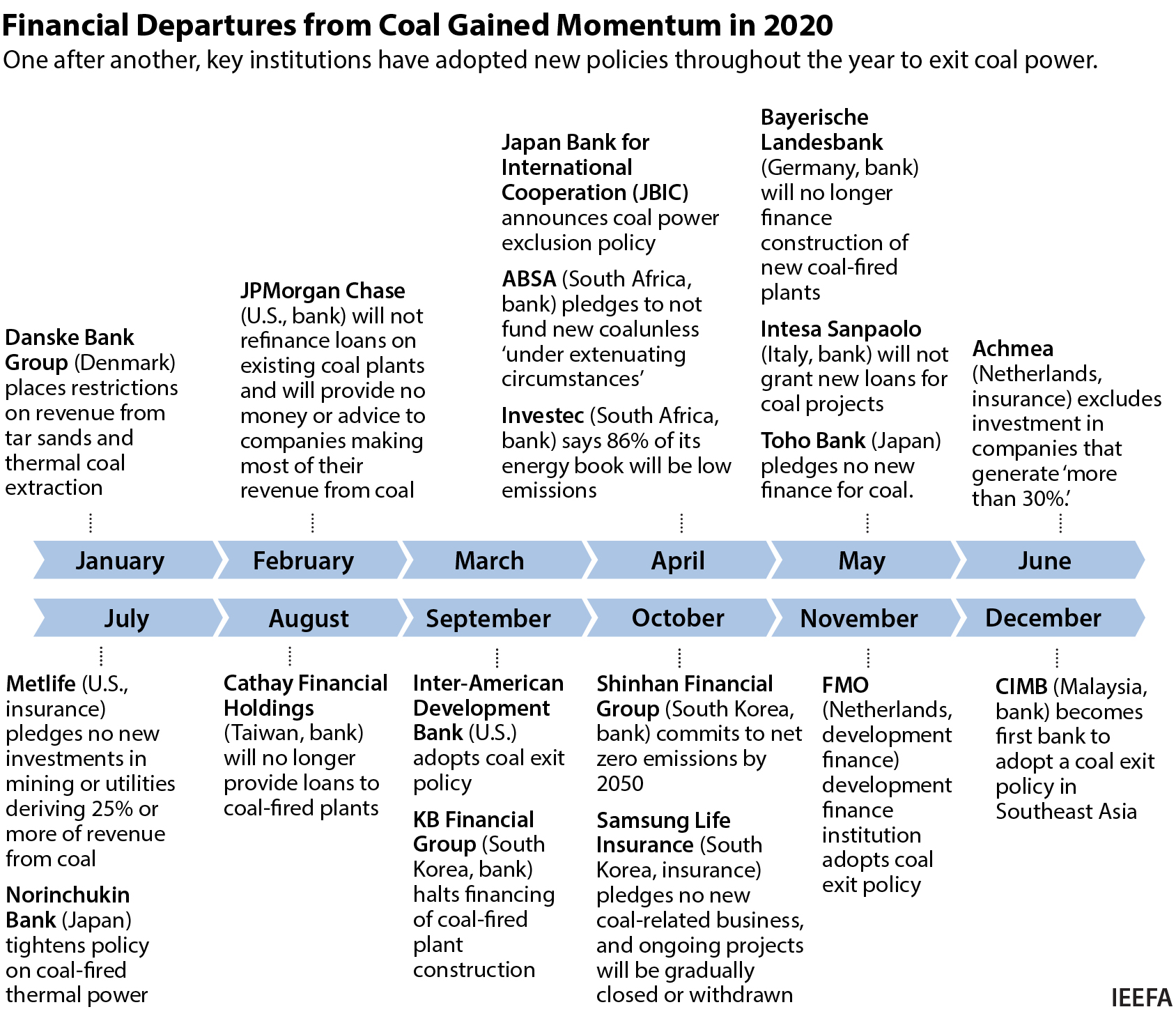

IT’S A CONTINUATION OF A TREND THAT STARTED TO GATHER PACE IN THE SECOND HALF OF 2020. Asia began this year as a global laggard, with very little climate finance risk discussion, and no credible coal exclusion policies from globally significant financial institutions (GSFIs). Now we are seeing new energy and climate policies from Asian governments, corporates and financial institutions every week or two. As one of the world’s largest trading houses, Marubeni Corp of Japan was a leader in the region, moving in September 2018 (but it is not a GSFI).

In October 2020 Shinhan Financial Group was the first South Korean bank to commit to net zero emissions by 2050, aligning with Prime Minister Moon Jae-in’s 2050 carbon-neutral pledge for South Korea. This built on the world-changing commitment by President Xi Jinping in September 2020 to an aspirational target for China of net-zero emissions by 2060, and followed Japan’s new Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s pledge in October 2020 to reach net zero emissions by 2050, also a significant ‘ratchet-up’ in ambition.

Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) was individually the biggest provider of coal finance subsidies globally in the last five years, but in April 2020 its governor announced a new coal power exclusion policy. (Coal power is often mis-quoted as ‘dirty but cheap’, but this over-simplification ignores the pre-requisite statement that it is also now only viable with capital subsidies – almost all of which come from Chinese, Japanese and Korean export credit agencies).

Japanese trading house Sumitomo, lagging its peers on coal, is likely feeling heightened global investor pressure as a result.

This week saw climate laggard Glencore commit to net-zero emissions by 2050 – a move largely driven by a near complete phase-out of coal mining globally by the same date, and assisted by an unexpected almost 20% year-on-year collapse in coal production in 2020 alone.

As the former Bank of England governor Mark Carney highlighted, Japan went from zero to hero in terms of embracing the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) in 2019, to be the #1 country globally in terms of signatories (now at 294).

Consulting firm Wood Mackenzie recently highlighted the massive scope of the fundamental energy disruption underway, forecasting that China will need to cut 890 gigawatts (GW) of coal power plants and replace them with 2,020GW of wind (a tenfold increase on cumulative installs to 2020) and 3,100GW of solar (a twentyfold increase) by 2060 to deliver net zero.

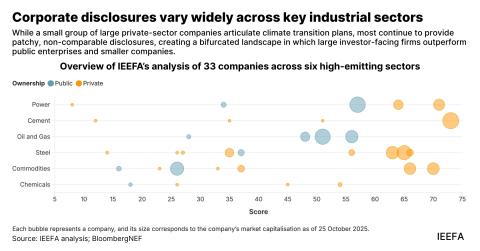

GSFIs are having to respond to and manage the financial risks of climate change and the energy transition. IEEFA is tracking formal fossil fuel exits, divestment and exclusion policies across GSFIs. This year alone there have been 65 announcements of new or improved policies specifically on coal mining and coal power, a 50% increase in the run rate relative to 2019, which itself saw a similar increase vs 2018.

THE FIRST GSFI TO MOVE, OR EVEN THE FIFTH OR THE TENTH, IS LARGELY SYMBOLIC. To date, there are now 151 GSFIs that have announced exits from coal. With more than US$10 billion of assets each for banks and insurers (and >US$50 billion for asset managers/asset owners), this now represents a material part of the global financial system.

It is now widely reported that there are almost no debt or equity financiers of coal assets. This not only applies to mines and coal power plants but increasingly to dedicated coal railways and coal ports as well, as Dalrymple Bay Coal Terminal found this week with its debut trading showing a 13% decline on the initial public offering price.

The music has slowed dramatically, and everyone now knows it has to stop.

Coal is the most carbon-intensive fuel source, and the one most technologically and economically challenged by the current global energy transition. Those still funding coal assets will be left without a chair.

For financial markets, this is principally about economics and technology, not morality.

Mark Carney described a globally systemic financial sector risk in his seminal 2015 Tragedy of the Horizons speech. It is no longer over the horizon; the financial risk is now.

BlackRock CEO Larry Fink’s January 2020 “fundamental reshaping of finance” letter was the catalyst for GSFIs globally to realise that if the US$7 trillion BlackRock was divesting thermal coal, it is time to do the same. By November 2020 he was talking of a “tsunami of change” as asset allocators move capital away from fossil fuel investments. I’m sure BlackRock regrets not divesting Exxon Mobil the same day it divested Peabody Energy. As Larry Fink said, for financial markets, this is principally about economics and technology, not morality.

BP CEO Bernard Looney’s February 2020 maiden speech will also go down in climate finance history as a seminal moment. It flagged that while coal is the weakest member of the fossil fuel herd, fossil gas and oil are both also fundamentally challenged by climate change, and that for fossil fuel firms to survive long term, a pivot into zero emissions energy alternatives was key.

Coal is just the first step. IEEFA has now tracked 65 GSFIs with formal exclusion policies on Arctic drilling and / or oil sands, with the majority of these only announced this year.

The contagion is real. Peabody Energy shares are down more than 80% this year. Exxon Mobil is down a staggering 42%, destroying over US$100 billion of shareholder wealth just this year at a time when the U.S. market is up 15%. The financial markets are finally waking up to climate-related financial risk, and that fossil fuels are a wealth hazard.

CIMB’s announcement ups the ante for Malaysia’s other leading banks – such as Maybank, Public Bank and RHB Bank – who would be well advised to follow to avoid the clear and growing financial risks of climate change as the world increasingly commits to the critical global action and ratcheting-up of collective ambition required to achieve the Paris Agreement.