Key Takeaways:

Australia is expected to play roles both as a supplier of suitable feedstock and as a green iron producer. Yet Australian miners are missing the first wave of low-emissions iron production, supplied by iron ore miners like Vale, Rio Tinto’s IOC in Canada and LKAB in Sweden.

Australia must pursue two parallel options: leverage its vast magnetite deposits to join existing suppliers of higher-grade iron ore, and develop new pathways and technologies to upgrade Pilbara’s low-grade iron ore for use in low-emissions ironmaking.

New technologies that make Pilbara iron ore suitable for low-emissions ironmaking are essential for the wider decarbonisation of the global steel industry. But Australia can begin with existing technologies if it aspires to become a green iron superpower.

24 September 2025 (IEEFA Australia): Australia risks being left at the starting blocks in the race for green iron if it waits for a universal solution to the technological challenges facing the industry, according to a briefing note released today.

Despite the challenges and costs, prime movers in Brazil, Canada and Sweden are pursuing pathways to supply high-grade feedstocks for lower emissions iron production, stealing a march on Australia, the world’s biggest supplier of iron ore, as highlighted in Australia’s path to green iron.

Australian miners are conspicuously absent from this first wave. This is despite an abundance of resources and government ambition to make Australia a major supplier of feedstock and a producer of green iron for export, says Soroush Basirat, IEEFA’s Energy Finance Analyst, Global Steel.

“As the world’s biggest iron ore producer and exporter, Australia has no standalone iron production plants,” Mr Basirat says. “With little incentive to build domestic high-grade feedstock capacity, the entire value chain has never developed at scale. Whether Australia wants to produce iron or export raw material, it needs to reconfigure the value chain and set up a new system.”

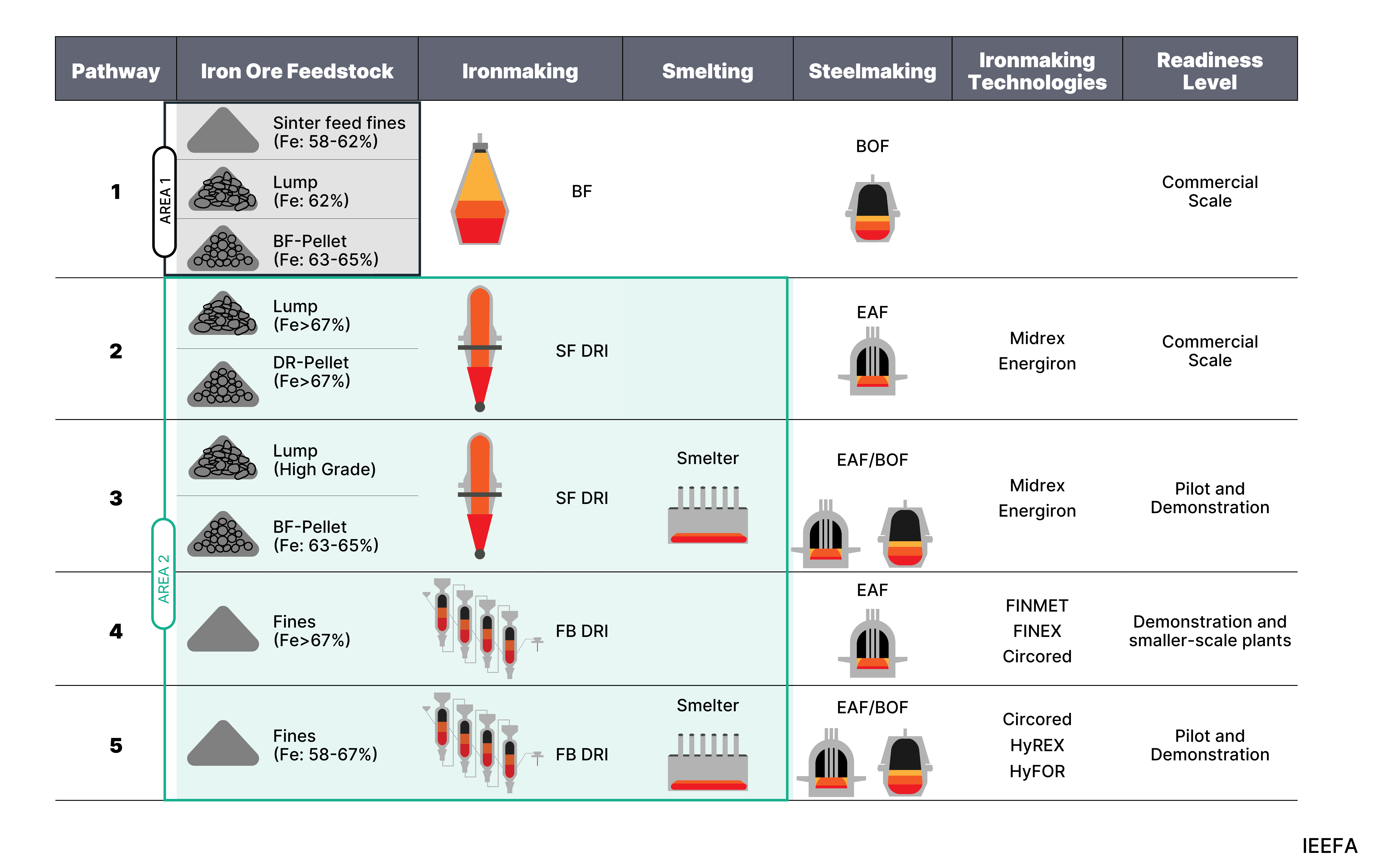

The Figure below shows the emerging pathways to produce green iron, utilising new and existing technologies or a combination of both. Australia’s green iron transition could take two routes:

Pathway 2: Enhancing feedstock supply for conventional shaft furnace DRI production. This pathway uses mature technology focuses on expanding the supply of high-grade iron ore concentrate and pellets, primarily magnetite-based, as feedstock.

“This presents two key challenges for Australia: producing high-grade ore, and processing it into pellets,” Mr Basirat says. “Major Australian iron ore miners are seeking technological solutions to these challenges.”

Pathways 3 and 5: Develop solutions for low- to mid-grade iron ore in the DRI pathway. The aim is to enable use of Australia’s vast, but lower-grade iron ore resources and manage higher levels of impurities. While promising, success hinges on technological advances in continuous smelting at scale for steel, and the direct use of fine ores in the DRI process, eliminating the pelletising stage. Pathway 4 also requires high-grade iron ore; however, fluidised bed technology is not as widely used as shaft furnaces.

Pathways for iron and steel production

Source: IEEFA. Notes: SF = shaft furnace, FB = fluidised bed, BOF = basic oxygen furnace, BF = blast furnace, EAF = electric arc furnace. Area 1: grey, represents the focus of Australia’s iron ore mining. Area 2: light green marks the area targeted for green iron development.

In the race to supply suitable feedstocks (concentrate or pellet) for low-emissions iron production, Brazil and Canada lead the way. Australia holds the world’s largest magnetite deposits outside Canada. While Canada’s ore is higher-grade and concentrated in one region, Australia’s deposits are lower-grade and scattered across remote areas.

“Other nations can provide these feedstocks at scale, and are expanding their capacities,” Mr Basirat says. “When it comes to supplying high-grade materials, Australia is not yet ready to meet the needs of the evolving green iron industry.”

With Australia’s iron industry at a crossroads, which pathway should it take: Enhance feedstock supply for conventional shaft furnace DRI production? Or develop solutions for low- to mid-grade iron ore in the DR pathway?

“The short answer is both, although the required priorities vary in their significance,” Mr Basirat says. “Technology providers believe the breakthrough technologies already exist for the transition to green iron, but need time to become commercially viable. While these solutions are being developed, it is important to continue investing in mature technologies.

“The ironmaking industry has always evolved through competing processes, with some scaling to millions of tonnes of production while others never move beyond pilot scale. So, relying only on next- generation technologies is too risky for a country aiming to be a leader in the green iron market.

“Australia’s ambition to become a green iron producer must begin with developing the entire value chain domestically, or it will lose ground to competitors.”

Read the note: Australia’s path to green iron

Media contact: Amy Leiper, ph +61 414 643 446, [email protected]

Author contacts: Soroush Basirat, [email protected]

About IEEFA: The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) examines issues related to energy markets, trends, and policies. The Institute’s mission is to accelerate the transition to a diverse, sustainable and profitable energy economy. (ieefa.org)