Will the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) ever be constructed? Public dissent has been mounting and financial hurdles have yet to be resolved. Continued delays only make the conclusion of this on-going saga more uncertain.

The Project

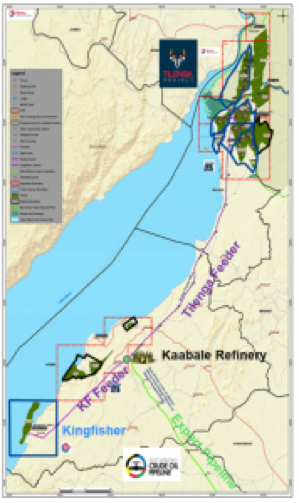

EACOP is being constructed in parallel with the Tilgenga and Kingfisher upstream development projects. Tilenga, owned by TotalEnergies will produce some 200,000 barrels of oil per day (bopd) and Kingfisher, owned by China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) will produce some 40,000 bopd. Each development will consist of a Central Processing Facility (CPF) to separate and treat the oil, water and gas produced by the wells. Kingfisher will have 4 well pads and a CPF and Tilenga has 31 well pads. The Ugandan Refinery project has a right of first call to 60,000 bopd, with the remainder of the oil being exported via EACOP.

EACOP will have a length of 1,443 km and export crude oil from Kabaale – Hoima in Uganda to the Chongoleani peninsula near Tanga port in Tanzania. At peak capacity it will handle 246,000 bopd.

The project dates its origins back to 2004 when Tullow Oil gained three exploration blocks following its acquisition of Energy Africa. In April 2020 Tullow sold all of its oil assets to TotalEnergies for $575 million in order to reduce its debt and strengthen its balance sheet. TotalEnergies’ vision was simple: purchasing Tullow Oil assets for next-to-nothing made it a no-brainer to move on to developing Tilenga and together with CNOOC, Kingfisher and EACOP.

The Next Hurdle

Time and events on the ground have proven difficult.

For example, the European Parliament’s resolution of September 2022, condemning human rights in Uganda and Tanzania, linked to investments in fossil fuel projects, have proven embarrassing to the French oil giant.

French President Emmanuel Macron has also indicated that France does not support this project.

Various interest groups have been extremely vocal and successful in their stand against the project:

The Climate Accountability Institute (CAI) has charged that during the project’s 25-year lifespan, associated oil emissions would be more than double those of Uganda and Tanzania in 2020.

Omar Elmawi, coordinator of the Stop EACOP campaign, said: “EACOP and the associated oilfields in Uganda are a climate bomb that is being camouflaged as an economic enabler to Uganda and Tanzania. It is to the benefit of people, nature and the climate to stop this project.”

Stop EACOP Campaigners argue that, as the world's longest heated oil pipeline which will run through many populated areas, it will contribute to poor social outcomes for those displaced by the project. They also mention the significant risk to nature and biodiversity, as the pipeline runs through large areas of savannah, zones of high biodiversity value, mangroves, coastal waters, and protected areas, before arriving at the coast where an oil spill could be devastating.

According to Elmawi, TotalEnergies is still in search of $3 billion in order to complete the financing of EACOP. To date, 24 banks, 18 insurance companies, and export credit agencies in France, Germany, Italy and the UK have refused supporting this project. Already the project has suffered a three-year delay.

How much delay can TotalEnergies withstand before it walks away from the project and demands impairment charges? The delay will also ensure that TotalEnergies’ financial team will be re-evaluating their energy portfolio. Think back to the summer of 2020 when TotalEnergies announced a $7 billion impairment charge for two Canadian oil sands projects. This might have seemed like an innocuous move, merely an acknowledgement that the projects hadn’t worked out as planned.

Yet it opened a Pandora’s Box that could change the way the industry thinks about its core business model—and could offer a new way forward in the energy sector.

While TotalEnergies wrote off some weak assets, it did something else: it began to sketch a blueprint for how to successfully transition an oil company into an energy company.

Patrick Pouyanné, TotalEnergies’ chairman and chief executive, said that by 2030 the company “will grow by one-third, roughly from 3 million boepd (barrels of oil equivalent per day) to 4 million boepd, half from LNG, half from electricity, mainly from renewables.” This was the first time that any major energy company had translated its renewable energy portfolio into barrels of oil equivalent. So, while the company slashed “proved” oil and gas from its books, it added renewable power as a new form of reserves.

TotalEnergies’ emphasis is on ensuring that its LNG portfolio and its renewables continue to grow to ensure shareholder income. Pesky oil projects which mobilize climate opposition and encourage environmental activism, both local and international, are not the type of activities that promote shareholder stability and satisfaction.

Finally, the UN COP27 climate conference, will no doubt also issue a rallying cry for stopping EACOP. Could EACOP become a stranded asset in Africa much like the Keystone XL Pipeline in North America?