Key Findings

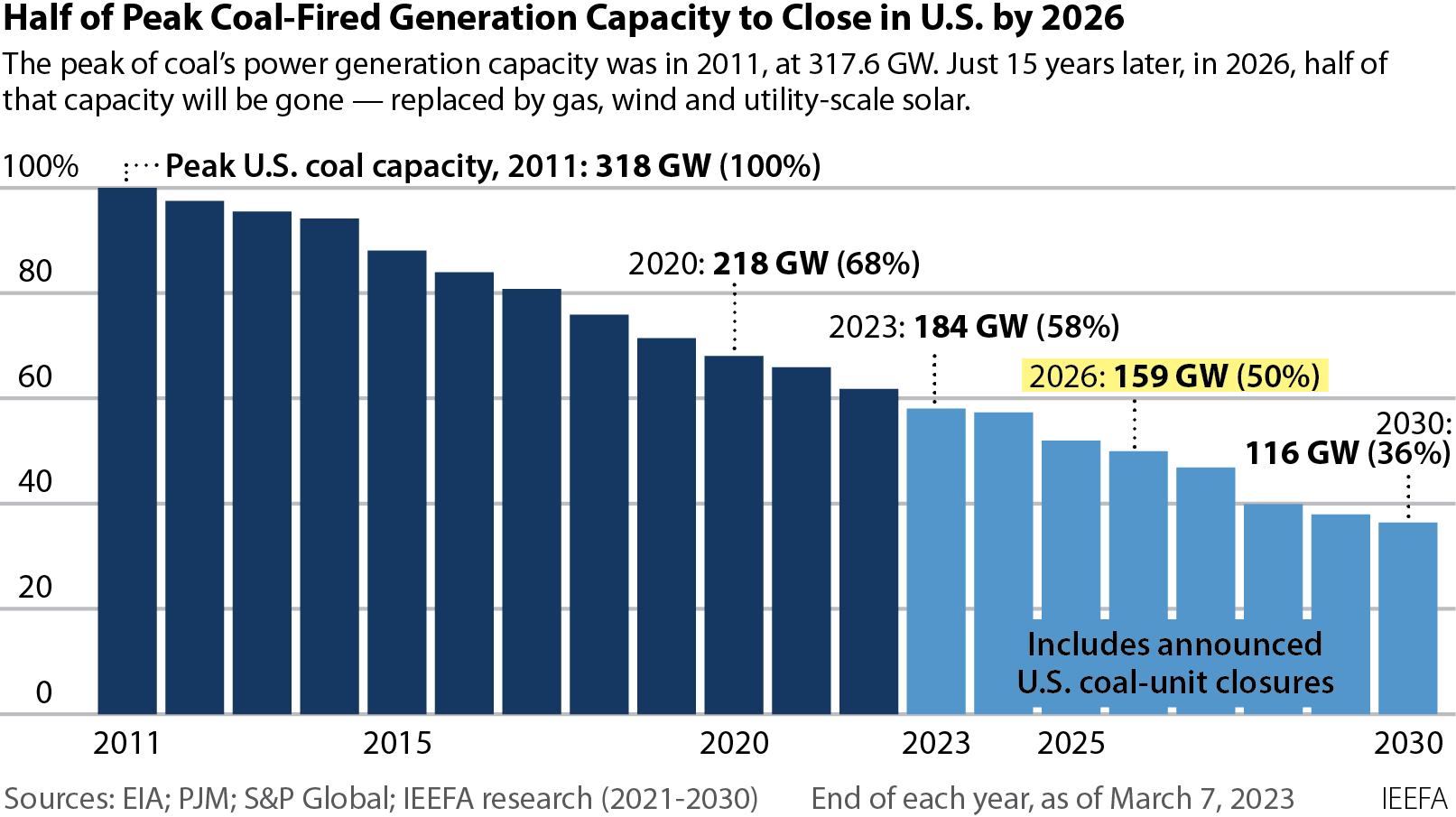

The U.S. is on track to close half of its coal-fired generation capacity by 2026, just 15 years after it reached its peak in 2011.

Roughly 40%, about 80.6 gigawatts, of remaining U.S. coal-fired capacity is set to close by the end of 2030.

Fewer than 200 large-scale coal-fired units (50 MW or more) remain without announced retirement dates, and 118 of those are at least 40 years old.

Coal use by U.S. electric-power producers is falling quickly again after a short-lived post-pandemic recovery, possibly falling to only 400 million tons in 2023—less than half of what was used just 10 years ago.

Executive Summary

The United States is rapidly approaching a milestone in the electricity sector’s energy transition: By the end of 2026, it will have closed half of its coal generation capacity, which peaked in 2011. This is now the earliest date for this milestone since IEEFA began closely tracking coal-plant retirements, and it has moved up despite pandemic-induced supply disruptions that have led to delays in the completion of new generation resources and significant price volatility for gas, both of which contributed to some shifting dates for plant closures. By another measure—actual electricity generation—the U.S. has cut coal use even faster, producing less than 50% of coal’s 2011 power level in both 2020 and 2022.

By the end of 2026, based on current announcements from utilities, coal capacity will fall to 159 gigawatts (GW), down from 318GW in 2011. It is set to fall to just 116GW by 2030. And coal generation may continue to fall faster, as aging units face higher operation and maintenance costs, and utilities increasingly favor the responsiveness of gas generation and battery storage to complement the variable output from solar and wind, both of which continue to be built at a rapid clip.

Together, these milestones portend an ongoing and deep restructuring of the U.S. coal industry as demand for the fuel continues to drop quickly. It is likely to result in significant mine closures, layoffs, and falling tax and royalty payments in coal-producing states.

From 2023 through the end of 2030, more than 80GW of coal generation is currently set to close, with about 10.5GW of that expected to be converted to run exclusively on gas. While there have been some delays to retirement dates over the past year (partly from replacement power projects missing construction deadlines), there has also been an acceleration in retirement dates at other plants. As a result, the overall pace of retirements has remained steady, but will be quite variable from year to year. For example, record levels of closures may occur in 2025, with 17GW announced, followed by just 6GW in 2026, and then surging to 22GW in 2028. Overall, utilities appear increasingly committed to these coal unit retirement plans as their long-term spending and resource plans are implemented. In fact, the most significant shift has been the addition of more planned wind, utility-scale solar, and battery storage capacity as utilities respond to financial incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act passed last year by Congress.

Overall, the closures are widespread. The 173 coal-fired units closing between now and 2030 are located in 33 states, and another 55 units with announced closure dates between 2031 and 2040 are spread across 17 states. The closures also reflect the aging of the U.S. coal fleet. In most years, the average in-service date of the retiring units occurred in the 1970s—meaning that the majority of units will be more than 50 years old when they are closed. Into the 2030s, the average age at retirement rises to 60 years or more. For utilities, the rising cost of maintaining and operating these units, especially when cheaper, more flexible, and far more technologically advanced generation alternatives are available, makes retirement an increasingly attractive option.

As in past years, IEEFA expects the list of announced coal unit closures to continue to grow, shortening the list of the remaining units. The closure of the coal-fired units means a permanent shift in the mix of fuels used to power the U.S. electrical grid, since no new coal plants are being built to replace them. In 2011, when the peak of U.S. coal-fired generation capacity of 317.6GW was reached, coal was easily the most important fuel for the electric sector, responsible for 44% of the power produced. But a boom in gas plants—largely using inexpensive gas from fracking—and the rapid growth in wind and utility-scale solar facilities has put an end to coal’s supremacy. By the end of 2022, U.S. coal-fired capacity fell below 200 GW, a 38% decline. Power production has fallen even faster: In 2022, coal produced only 20% of the sector’s electricity, less than half its market share a decade ago. Already this year, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) expects coal’s market share to fall to 17%, and with another 80GW closing by 2030, IEEFA estimates that there is a strong possibility that coal’s power-market share will fall to 10% or lower.