Texas needs to go big on carbon capture proposal

Key Findings

Texas has raised its threshold for designating carbon capture facilities as “clean energy projects,” but its 75 percent level is still too low

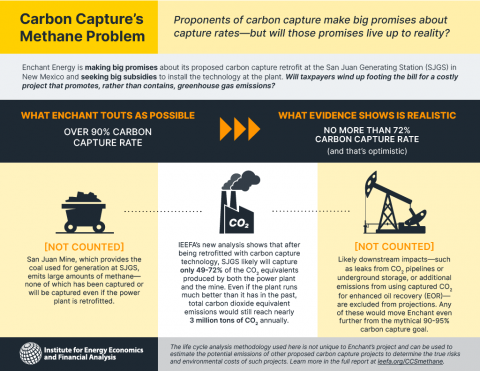

Results from carbon capture projects have not been promising, with developers failing to meet less ambitious goals

Texas should increase its carbon capture threshold to at least 95 percent for facilities to secure “clean” status

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) is no fan of carbon capture technology. Our research shows that existing projects have failed to meet their capture targets, and we believe support for new facilities, particularly in the power sector, only delays efforts to transition away from fossil fuels. But if Texas wants to embrace carbon capture, especially for its petrochemical sector, it should go big and lead by example.

Pending legislation that would designate carbon capture facilities as “clean energy projects” was introduced with a laughably low target of 50 percent. The threshold for securing “clean” status has since been raised to 75 percent, but even that is too low given that proponents now widely claim much-higher capture rates are both doable and economic.

In a report last year, the International Energy Agency noted that “there are no technical barriers to increasing capture rates beyond 90 percent.” Ongoing testing, the organization said, shows that “capture rates as high as 99 percent can be achieved.”

Technology developers are just as optimistic.

Mitsubishi says that the latest version of its carbon capture technology product, an amine-based solvent known as KS-21™, is capable of capturing 99.8 percent of the carbon dioxide emissions from industrial processes and power generation. Similarly, Shell says its CANSOLV amine solvent “can secure up to 99 percent of the CO2 from post-combustion, low-pressure off-gases.”

IEEFA is doubtful.

Mitsubishi used an earlier version of its solvent at the now-closed Petra Nova carbon capture project southwest of Houston. IEEFA’s research showed clearly that the facility’s overall capture rate was between 70 and 75 percent during its three years of operation—far below the promised 90 percent often repeated by the technology’s proponents. IEEFA’s figure includes the emissions from a non-controlled gas plant used to run the capture equipment, as well as emissions from days when the power plant (Unit 8 at the W.A. Parish station) was generating electricity but the carbon capture equipment wasn’t running.

Shell supplied the carbon capture equipment at SaskPower’s Boundary Dam Unit 3 in Saskatchewan, Canada. The facility, the only other CO2 capture project installed on a coal-fired power plant worldwide, has been operational since the end of 2014. The results have not been promising. IEEFA research has shown that the facility has never hit its original capture goal of 1 million metric tons of CO2 per year, averaging just 625,000 metric tons annually during its eight full years of operation.

These real-world examples drive IEEFA’s skepticism about the long-term, commercial-scale performance of CCS—achieving a 90 percent or higher carbon capture rate every year for decades to come will be difficult. However, if the technology providers are going to claim that level of performance is possible, then Texas should hold them to it.

Legislators should require that CCS facilities achieve at least a 95 percent capture rate to be deemed a clean energy project. Anything less would amount to a costly pollution giveaway. Adding teeth to the measure would also be advisable: If being deemed a clean energy facility is important, then taking that designation away for failure to meet the 95 percent capture threshold likely would serve as a significant incentive for consistent, high-level performance.