South Korea needs to address its vicious cycle of power trilemma

Key Findings

South Korea’s vicious cycle of power trilemma underscores the importance of rationalizing the country’s power tariff system as a key starting point to resolve complex issues.

For the 22nd National Assembly, the delayed energy transition is a major factor in high energy bills due to rising climate-environmental surcharge, missed opportunity costs amid impending grid parity, and negative externality costs resulting from stringent regulations.

Addressing South Korea’s power trilemma of energy security, market competitiveness, and sustainable development can help the country mitigate its ballooning energy costs and break free from its dependence on imported fossil fuels.

During South Korea’s 22nd National Assembly election, addressing the climate crisis was one of the major promises made by most parties. Survey results indicated that around 33% voted based on climate policies.

The newly inaugurated national assembly will likely implement common pledges, including expanding the country’s Climate Change Fund and increasing the proportion of the Emissions Trading Scheme with auctioning.

The new assembly is expected to discuss the rationalization of power tariffs as one of its urgent agendas, frozen from mid-2023 until the second quarter of 2024.

Low-regulated power tariffs, combined with the high costs of imported fossil fuels, were two of the main reasons why state-run power utility Korea Electric Power Corporation’s (KEPCO) debt reached an unprecedented ₩202.5 trillion (US$146.6 billion) in 2023.

Ending the country’s power trilemma

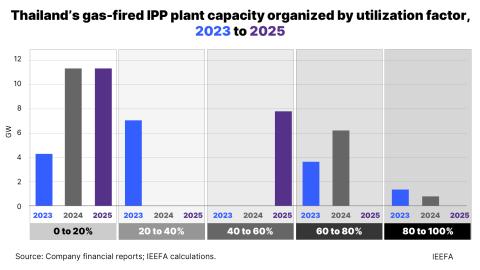

A recent IEEFA report identified fossil fuel-centric energy security and a non-competitive power market structure as the root causes of KEPCO’s mounting debt.

Fossil fuels, including liquefied natural gas (LNG), accounted for 63.6% of South Korea’s power generation, higher than the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development average of 52.2% in 2022.

The surge in LNG prices since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 drove up fuel costs for power generation and pushed up the wholesale power price that KEPCO pays to generation companies.

Yet, the government opted to maintain low-regulated power tariffs for end-users despite KEPCO’s higher costs. KEPCO sold electricity to retail customers at massive losses, exacerbating the company’s financial woes.

South Korea’s power pricing structure has traditionally been government-regulated to prioritize price stability, reduce the burden on taxpayers, support industrial production, and promote economic growth. Maintaining low power tariffs is also politically significant, particularly during elections.

As a result, KEPCO, already burdened with debt, was unable to reflect the surge in fuel costs in power tariffs and had to continuously resort to issuing corporate bonds as a temporary measure. KEPCO’s bonds reached ₩80.1 trillion (US$58 billion) in 2023.

Despite concerns about KEPCO’s debt levels, the government revised the KEPCO Act in December 2023, raising the company’s bond issuance limit from two to five times its capital and reserves.

The reliance on bond issuance by state-run energy companies such as KEPCO and KOGAS to address their financial challenges raises significant concerns about potential “double moral hazard.” Due to implicit government guarantees of financial support, debtors have no incentive to innovate or reduce costs to boost competitiveness and efficiency.

Implicit government guarantees could also decrease creditor scrutiny and discourage them from being more selective when investing in assets, potentially leading to continued investment in outdated fossil fuel assets.

This vicious cycle of power trilemma underscores the importance of rationalizing the power tariff system in South Korea as a key starting point to resolve complex issues.

IEEFA’s recent report warns that “pseudo competitiveness” and “double moral hazards” may have significant repercussions, such as increased government debt and higher taxes for future generations. Under the guise of controlling inflation, politicizing power tariffs and reliance on bond issuance for loss mitigation may create a vicious cycle that inadvertently exacerbates existing financial challenges.

Maintaining artificially low electricity tariffs presents a trade-off, as consumer benefits may come at the expense of significant financial burdens for public energy companies, the government deficit, and, ultimately, future taxpayers.

Breaking free from fossil fuel dependence

For the 22nd National Assembly, the delayed energy transition is a major factor in high energy bills due to rising climate-environmental surcharge, missed opportunity costs amid impending grid parity, and negative externality costs resulting from stringent regulations.

In this sense, pledges by the Democratic Party of Korea, such as tripling renewable energy by 2030 and enacting the Korean Inflation Reduction Act, are encouraging. However, the commitments made by political parties for this election must materialize through tangible policymaking.

According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, renewable energy in South Korea is expected to achieve grid parity by 2027, when the electricity generation costs for solar PV equate to that of coal-fired power. IEEFA believes that South Korea’s delayed energy transition could lead to missed opportunities for cost reduction as renewable technologies continue to improve.

Growing international climate initiatives, such as RE 100 (Renewable Energy 100), Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, and Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, could impose increasing negative externality costs on South Korea due to its delayed energy transition.

Addressing South Korea’s power trilemma of energy security, market competitiveness, and sustainable development can help the country mitigate its ballooning energy costs and break free from its dependence on imported fossil fuels.