The Lasting Impact of the Anti-Keystone Campaign

We don’t know for sure yet whether President Obama will allow the Keystone XL pipeline to be built. But we do know the public campaign against the project has been a resounding success in the way it has elevated public awareness of the risks tied to such development.

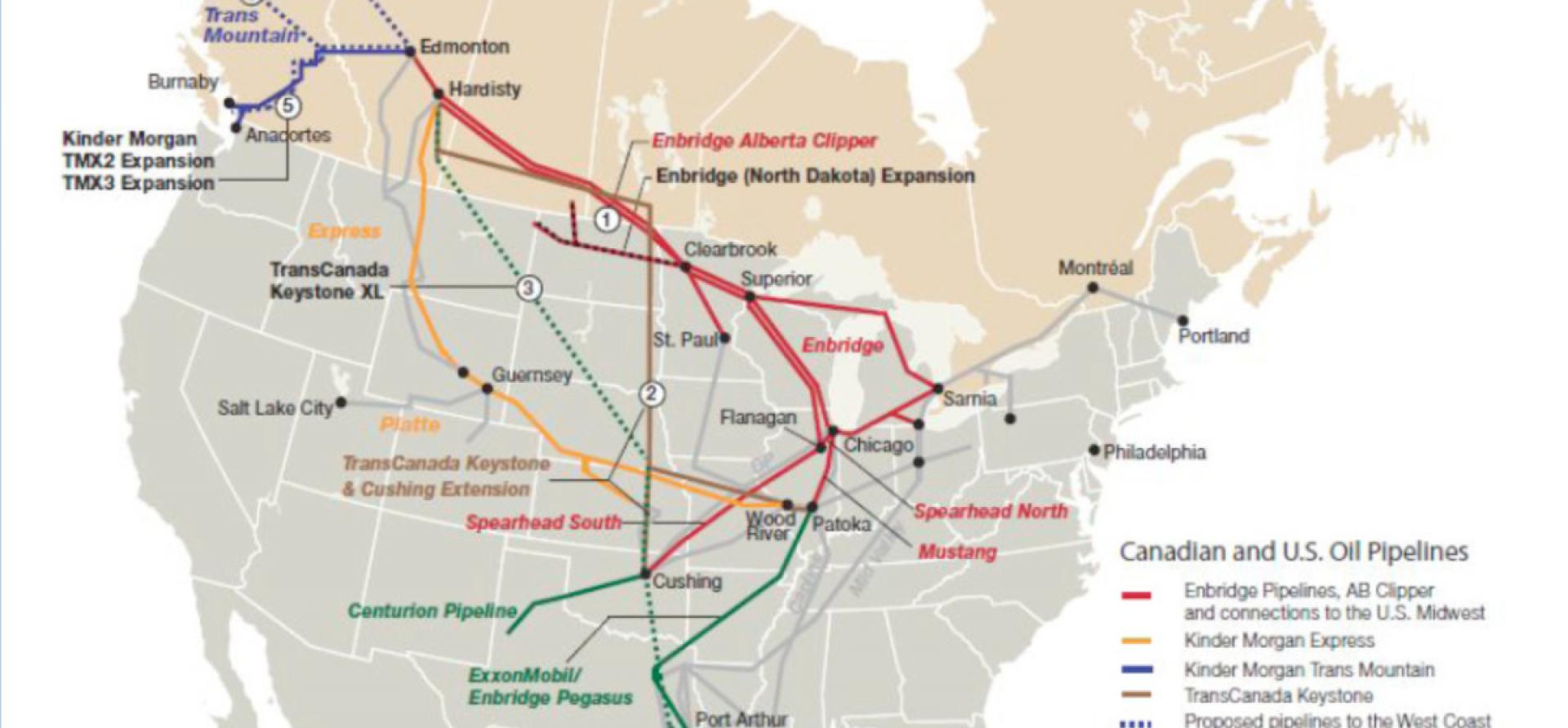

Long ribbons of oil and gas pipeline already crisscross North America because of a tradition that dictated for most of the past 100 years that whenever oil or gas companies pitched a pipeline, it got built, and it got built with scant review. Pipelines rarely even encountered opposition except from those whose land would be taken by the pipeline company through eminent domain. Most of the time, pipeline plans have sailed through government approval processes.

It’s been a different story, thankfully, with Keystone, the crucial piece of infrastructure in moving a proposed 800,000 barrels a day of petroleum from oil sands fields in Alberta all the way to the Gulf Coast of the U.S.

Keystone today has become bigger than Keystone, in a way, standing now as an emblem for public resistance to reckless energy projects. Largely as a result of Keystone, pipeline projects are now controversial just about everywhere they’re proposed. Enbridge, a major pipeline company that used to hide behind its low public profile, now faces opposition wherever it tries to build. Efforts to move natural gas by pipeline between Pennsylvania and New York have run into trouble, and a similar battle has been playing out in Virginia.

It all reminds me of the movement a decade ago against new coal-fired power plants in which public refusal to accept the over-reaching ambition of the coal and utility industries served to curb that ambition. More than 150 coal-fired projects at issue bit the dust before they ever left the drawing board, and much of the resistance came from grassroots opposition in places not especially known for being populated with tree-huggers and liberal do-gooders.

Deep opposition surfaced in coal country itself and in other very conservative parts of the U.S. Local resistance to proposed coal plants contributed to cancellations in Georgia, Kentucky, Ohio and South Carolina, and the coal industry ended up suffering a rout from which it has never recovered. Today, as the energy economy evolves, hardly a week goes by without a new announcement about the impending retirement of a coal-fired plant.

In North America, at least, I think there’s some hope at last that a grassroots opposition to oil and gas infrastructure is emerging that could one day rival the extent of the opposition to coal infrastructure that took off 10 years ago.

This new resistance is not just about pipelines. Opposition is gaining momentum and intensity against coal trains, for instance, against coal-export port development and against train-to-barge projects in the Northeast and the Pacific Northwest. Even along the Gulf Coast—a region that has long been too friendly with the oil industry—more questions are being asked than ever about the damaging effects of that industry.

Some well-meaning critics of this rising opposition argue that resistance is futile, that if a project doesn’t get built in one location it will be built somewhere else. These skeptics suggest that there’s no point in opposing projects like Keystone because the oil industry is too nimble to be outdone.

Such naysayers were wrong 10 years ago and they’re wrong again today. The oil industry doesn’t look all that nimble to me. In fact, its leaders seem at a complete loss as to how respond effectively to Americans and Canadians from all walks of life who have joined against them to prevent more environmental damage and to curtail greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to the growing possibility of global disaster.

I’m sure these fights will play out differently than they did 10 years ago and that opponents of pipeline construction and coal-industry expansion won’t win every fight. But they’ll win lots of them.

I sure hope President Obama doesn’t let the Keystone pipeline proceed. Whatever he decides, though, the legacy of the campaign against the pipeline is already clear. Every significant fossil-fuel infrastructure project in the U.S. today faces serious opposition. Many of those projects will be defeated, and lots of fossil fuel, as a result, will remain in the ground—where it belongs.

That seems like a victory to me.

Larry Shapiro is IEEFA’s board president and associate director for program development at the Rockefeller Family Fund.