IEEFA U.S.: The federal government’s updated electricity-generation forecast seems already outdated

The Energy Information Administration’s release this week of its Annual Energy Outlook includes indications that the agency is beginning to incorporate rapid price renewables-sector declines into its market modelling.

But the outlook—like those at the agency that have come before it—still appears out of touch with structural declines in coal and, notably, not very well wired into the rise of wind.

Call it half a loaf.

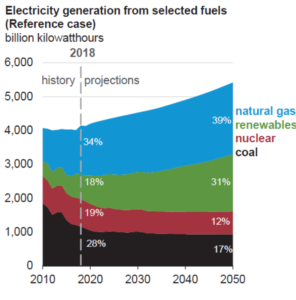

The agency is projecting continued strong growth in overall renewable power generation during the outlook’s forecast period, which runs to 2050 (see the screenshot below). All told, the EIA expects renewables’ share of U.S. electricity generation to climb from 18% last year to 31% by 2050. Such growth will push renewables ahead of both nuclear and coal in the 2020s to take the second spot behind natural gas.

The agency has this growth being driven almost solely by increases in solar-photovoltaic generation, particularly through utility-scale projects. Here, EIA expects installed capacity to climb from just over 30 gigawatts (GW) in 2018 to more than 215 in 2050—some 40GW more than it had in its outlook a year ago.

But where it seems to be moving, on the one hand, toward more accuracy than it has in the past, it misses with the other: The outlook has utility-scale PV installations rising alongside significant declines in generation across the commercial, industrial and residential solar sectors for smaller-scale installations. Specifically, the EIA sees 186GW of what it dubs “end-use capacity” installed by 2050; last year it projected 251GW of such capacity by 2015. EIA says its reduction on that figure is due to the economics-driven nature of its National Energy Modeling System, which it has apparently updated over the past year and which is the backbone of its annual outlooks. The problem with this line of thought, however, is that it does not acknowledge the clear possibility that corporate and individual decision-making will transcend strictly economic considerations and very likely add to the growth of solar.

AS PUZZLING AS THAT SOLAR ASSESSMENT IS, IT IS NOT AS BAFFLING as the EIA’s treatment of wind generation. The agency has installed wind capacity ticking past 118GW in 2022—and then growth remaining essentially flat through the end of the decade, rising to only 118.6GW by 2029. It has, installed wind capacity climbing to 134.7GW by 2050 based on an anemic growth rate of 1.1%.

For comparison, the latest data from the American Wind Energy Association shows just over 90GW of installed wind capacity today, with an additional 20.7GW currently under construction. AWEA reports an additional 17GW of capacity in the advanced-development pipeline (projects “having signed a power purchase agreement, proceeding under utility ownership, or announcing a firm turbine order”). All told , these figures show installed wind capacity nationally reaching 128GW over the next two years—8% more than what the EIA model sees a full decade from now.

EIA’s projection are hard to square with the price-driven reality of what is really happening. The latest Lazard analysis of the current levelized cost of unsubsidized wind power ranges from $29-$56 per megawatt-hour—less than the cost of new coal and nuclear and competitive with existing coal.

How the EIA model can be so far off track from what AWEA says is a mystery, but it is not the only odd element in the agency’s new outlook.

To its credit, the EIA has updated its coal-plant retirement analysis and now estimates that 43.1GW of coal-fired capacity will be shut from 2019-2024 (IEEFA estimated last fall that 36.7GW of coal capacity would be closed through 2024). Further, the agency now expects more coal plant closures than it has previously forecast into the 2030s, when it has coal-fired capacity plateauing at roughly 150GW; last year’s report had that decline ending earlier and with a higher remaining total.

The problem with this assessment isn’t with the drop in installed capacity, it is what happens afterward. Beginning in 2034, EIA expects essentially no additional coal plant retirements through 2050. This flat-line projection flies in the face of operational reality. In 2017, the agency noted that roughly 34GW of the U.S. coal fleet was built after 1990—meaning that in 2050 that capacity would be 60 years old and at or beyond its normal life expectancy. The rest of the U.S.’ coal fleet is older, in many cases much older (105GW was built between 1970-1980 according to the EIA 2017 analysis), and the likelihood that it will still be running in 2050 is slim.

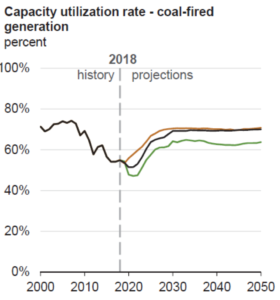

Further, EIA expects the aging coal fleet’s capacity factor to somehow climb in the years ahead, rising (see the second screenshot here) from a 50+% level in the early 2020s to around 70% in the 2030s—a number not seen since the first decade of this century.

PLANT AGE CLEARLY ARGUES AGAINST THIS DEVELOPMENT, and also stands in stark contrast to the operational transition that is occurring across the U.S. grid, which increasingly favors flexible resources that can ramp up and down to balance intermittent renewable energy generation.

Finally, the EIA in its analysis omits any consideration of non-numerical information, which is to say fast-evolving policy changes at major utility companies. This is kind of like predicting the weather without looking outside. Several of the largest U.S. current coal plant operators—including American Electric Power, Duke Energy, Southern Co. and Xcel Energy—have announced plans to transition away from coal and toward cleaner generation resources in the years ahead.

Those pronouncements may be hard to model, but ignoring them skews the EIA’s outlook unrealistically in coal’s favor.

Dennis Wamsted is an IEEFA editor.

Related items:

IEEFA U.S.: The gathering solar wave