IEEFA update: Commercial need for Trans Mountain Pipeline no longer holds – if it ever did

The Government of Canada is expected to rule by June 18 on whether the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion should move forward. In addition to possible legal challenges, the business case for the pipeline expansion continues to weaken. An updated financial analysis needs to be conducted before committing Canadian taxpayers to spending billions more on this non-competitive and risky project.

The Government of Canada is expected to rule by June 18 on whether the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion should move forward. In addition to possible legal challenges, the business case for the pipeline expansion continues to weaken. An updated financial analysis needs to be conducted before committing Canadian taxpayers to spending billions more on this non-competitive and risky project.

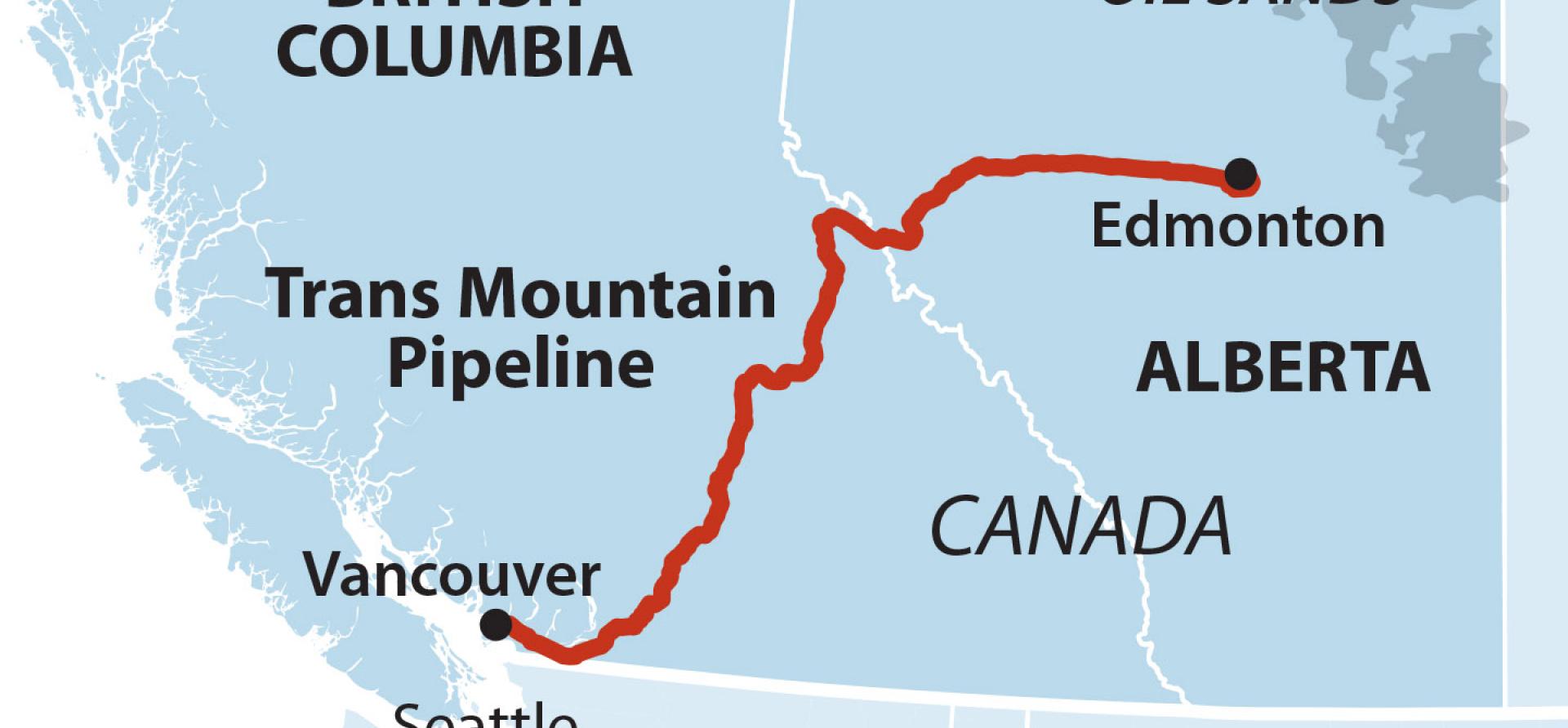

THE TRANS MOUNTAIN PIPELINE HAS A TROUBLED HISTORY. The Pipeline Expansion, if completed, would connect oil sands from Alberta to Canada’s West Coast, presumably for export to Asia. Over the past two years, the controversial project has faced many challenges. By May, 2018, its former owner, Texas-based Kinder Morgan, had all but walked away from completing the expansion, having lost its appetite for facing ongoing legal, environmental, and regulatory hurdles. Later that same month, the Canadian government made the extraordinary decision to buy the unfinished pipeline and related assets (primarily an ageing pipeline between Alberta and Puget Sound in Washington State) for $4.5 billion should another buyer not step forward. (NOTE: All figures are in Canadian dollars except where indicated otherwise). The Canadian Federal Court of Appeal, on August 30, 2018, formally halted construction. Thirty minutes after the ruling, Kinder Morgan shareholders approved the deal, and, two days later, the Canadian government had, in effect, become the buyer of last resort.

The true costs of acquisition, expansion and ongoing operation of the pipeline are not fully understood.

Since the pipeline purchase, the Government of Canada has structured its acquisition, planned expansion and ongoing operation in a way that makes it difficult to determine how much taxpayers are paying now and will pay in the future. A recently-released annual financial report by the Canadian Development Investment Corporation (CDEV) suggests that between September and December 2018, operating income ($48 million) from the related assets of the Trans Mountain sale (primarily the aging pipeline between Alberta and Puget Sound) did not cover the interest on the loan to buy the pipeline ($82.4 million – see CDEV Annual Report 2018 pages 56 and 61).

THE BUSINESS CASE FOR THE PIPELINE IS WEAK AND GETTING WEAKER AS OIL SANDS GROW LESS COMPETITIVE. Oil sands from Canada cost more than oil produced elsewhere and the price differential is going to grow.

- The product from the Alberta oil sands requires costly refinery processes in an era when abundant reserves of lighter, sweeter oil can be brought to market smarter, faster and cheaper. Despite aggressive industry efforts to lower costs to a competitive range, there has been no appreciable uptick in production rates or profitability. High-cost oil sands will put pressure on Canada’s exports to the U.S. – its largest customer – for the foreseeable future. And this unrelenting pressure will also complicate fledgling efforts to increase oil sands exports to Asia. These efforts to export to Asian and other major importers face stiff competition from other producers that have existing trade relationships and lower cost structures.

- Supertankers represent a super threat. So-called Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs) can carry two million barrels of oil, compared to oil tankers currently allowed through British Columbia’s shallow inlet that can only carry 550,000 barrels. Tankers have already begun transporting oil to China from the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP), the first terminal in North America that could accommodate VLCCs. A refiner in Asia would need to pay for four tankers to ship the same amount of Canadian oil sands from British Columbia as it would from the LOOP terminal, making oil from Canada even less competitive. Another competing VLCC terminal in Corpus Christi, Texas is expected to become operational in 2020.

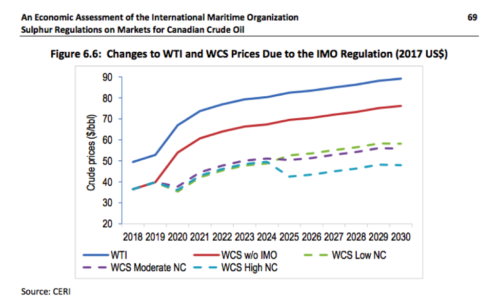

- New International Maritime Organization (IMO) rules governing sulfur content in maritime fuel go into effect in 2020 that will make oil sands less competitive. These new rules drastically reduce sulfur content in maritime fuel, to 0.5 percent sulfur content, down from the current level of 3.5 percent. These regulations will depress the price of Canadian oil, West Canada Select (WCS) compared to the other benchmark oil prices, especially West Texas International (WTI).The Canadian Energy Research Institute (CERI) in its recent report on the impact of the new IMO regulation, concluded that the differential between WSC and WTI would “grow with the introduction of the IMO sulphur regulation,” and that “approximately 500,000 bbls of oil sands production [is] at risk of becoming unprofitable.” The chart below illustrates the potential widening of the spread, from its historical range of US$6/bbl – US$37/bbl to approximately US$50/bbl.

WTI and WCS Price Differential (2017 US$) Due to the IMO Regulation

Significant amounts of fossil fuel reserves are already being sold at a loss during this time of global price volatility and political instability. Competitive forces are only increasing as more countries (such as the U.S. and Russia), enter the global market. These countries are bigger and can better withstand oil price fluctuations. At best, oil sands are marginally profitable.

Even viewed optimistically, the oil sands export potential suggests Canada will become, at most, a swing producer within the existing market structures. Since the pipeline was barely economically viable in its original configuration, expected delays and anticipated increases in construction costs cast further doubt on whether there is any business case for the expansion project at all. Best to figure that out before building it.

Tom Sanzillo ([email protected]) is IEEFA’s director of finance.

Kathy Hipple ([email protected]) is an IEEFA financial analyst.

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA update: U.S.-Canada trade tensions could scuttle Kinder Morgan sale of Trans Mountain Pipeline