IEEFA Update: America’s Coal Industry Is in Trouble

American coal industry executives have been working hard to restore investor confidence by arguing for a business-recovery rationale based on increased demand in export markets.

American coal industry executives have been working hard to restore investor confidence by arguing for a business-recovery rationale based on increased demand in export markets.

There’s not much evidence for this case.

Exports did help the industry in 2017, as several companies noted in their latest earnings reports, but U.S. coal producers are facing major problems with their largest customer, the domestic electricity-generation sector, which is moving steadily toward cleaner, cheaper fuels.

Arch Coal Inc. cited “positive momentum in international coking and thermal coal markets” as a key factor in its 2017 results. Similarly, Alliance Resource Partners said its increase in coal production last year was thanks to record exports. Likewise, CONSOL Energy, the newly independent coal company spun off by CNX Resources, touted exports through its marine terminal and said its average revenue per ton was up in 2017 “due largely to higher average revenue per ton on export shipments.”

The problem here is twofold.

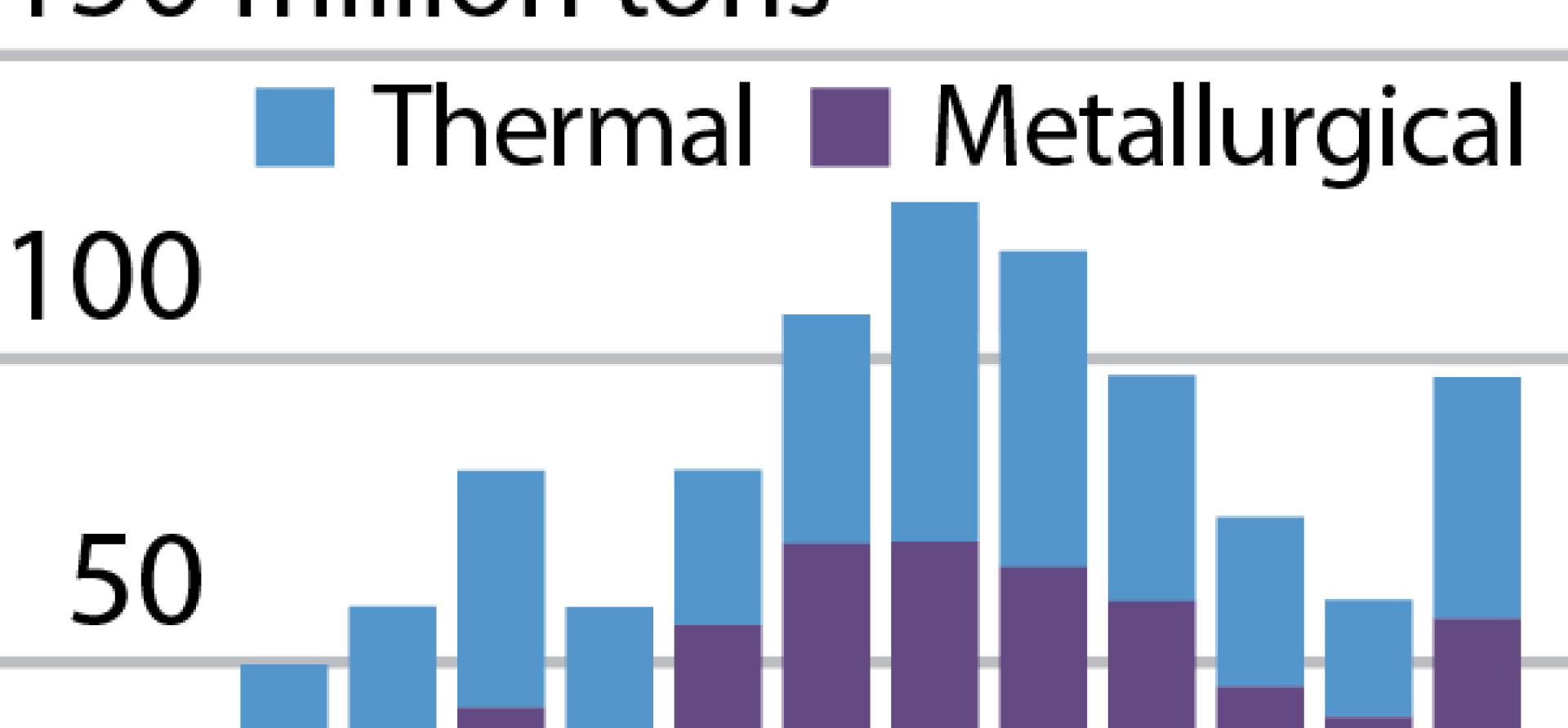

First, coal export demand and prices are notoriously volatile. Since 2006, U.S. coal exports have bounced around from a low of 50 million tons to 125 million tons in 2012 and 97 million tons in 2017, according to final figures from the federal Energy Information Administration. Betting on a market with such a roller-coaster history hardly qualifies as a long-term plan for growth. In its most recent Short Term Energy Outlook, released this week, the EIA has exports falling this year and then again in 2019.

Second, the U.S. coal industry’s health remains tied largely to U.S. customers, which is to say the owners of coal-fired plants, that account generally for about 90 percent of annual production. This market is shrinking steadily, continuing a decline that began in 2007. This market erosion will continue, in our view, and we see coal demand falling by 30 million tons in 2018.

THE LONG DECLINE OF THE U.S. COAL INDUSTRY stems from the fact that its customers are disappearing. Since 2010, at least 50,000 megawatts of coal-fired generating capacity have been retired. Those millions of tons of lost coal production aren’t coming back. We see an additional 15,000 megawatts of coal-fired capacity closing this year, with more retirements on the horizon in coming years.

A shift in capital investment by utilities and corporations increasingly favors wind and solar because of their declining prices.

While this trend has been driven in part by environmental mandates, the larger reason for it is that coal-fired electricity is no longer cost competitive with natural gas and renewable wind and solar energy. Natural gas prices increased by about 20 percent in 2017, an increase of the type that at one time would have led to increased coal consumption. But that didn’t happen, and with natural gas prices pegged to be relatively stable going forward, the uphill climb for coal only gets steeper.

Meanwhile, a shift in capital investment by utilities and corporations increasingly favors wind and solar because of their declining prices. Wind now accounts for about 6 percent of the nation’s electric generation overall, but in many Midwest and Plains states that have been coal-generation strongholds, wind’s market share is now well above 10 percent, and four states—Iowa, Kansas, Oklahoma and South Dakota— get at least 30 percent of their electricity from wind.

Solar investments are also up, a trend that poses yet another long-term threat to coal because solar helps curb prices during peak periods, when coal-fired power plants have traditionally earned most of their revenue. This is an issue to watch, particularly in Texas, where 3,500 megawatts of new solar capacity are expected to come online in the next several years, competing head-to-head with the state’s already distressed coal-fired generation sector

While the public-relations offices of coal producers are prone to glossing over market fundamentals like these, the Securities and Exchange Commission requires companies to publish their market expectations.

Digging into the financials at North American Coal Corp. reveals how the company is hoping to somehow grow but that “future opportunities are likely to be very limited.” Similarly, Peabody Energy acknowledged in its 2017 year-end results that plant retirements in the U.S. are expected “to reduce base demand [in 2018] by approximately 25 to 35 million tons.”

Just as revealing, Cloud Peak Energy, a major producer in the Powder River Basin of Montana and Wyoming—the biggest coal-producing region in the country—expects its output to fall again this year to somewhere between 52 million and 56 million tons from 57.4 million in 2017.

These coal companies may find some relief in overseas markets, which may help in the short term, but the longer-term picture is for continuing structural changes in U.S. coal markets that will leave too many producers mining too much coal for too few customers.

David Schlissel is IEEFA’s director of resource planning analysis.

RELATED NEWS:

IEEFA Report: U.S. Coal Market Erosion Continues

IEEFA Update: How Will Westmoreland Coal’s Deepening Spiral End?

IEEFA Update: A Lobbyist With Coal-Colored Glasses Can’t See the End Game