IEEFA U.K.: Smart tariffs can cut electric vehicle charging costs by one-fifth

Smart tariffs that have been enabled by the rollout of digital meters can cut the payback period on electric vehicles by more than one-fifth, according to U.K. data, and can help Britain achieve its target to ban all new gasoline and diesel cars by 2030, as announced this week.

IEEFA published research in May 2019 that assessed the payback period for buying an electric vehicle (EV) in multiple countries, including the United Kingdom. We measured the payback period as the number of years it would take for an EV owner to recoup the higher upfront cost that’s offset by lower fuel expenses.

In the intervening 18 months, quite a lot has changed, not least because of the coronavirus pandemic. The U.K.’s rate of inflation has fallen to 1.1%, from almost 3%. Gasoline prices have dipped to around £1.13 per litre, down from £1.20. And the U.K. has cut the EV purchase grant almost to £3,000 from £3,500.

Digital meters enable differential pricing according to peak and off-peak usage

Something else has changed. The U.K. is nearing a universal rollout of digital meters, which enable electric utilities to offer time-of-use electricity tariffs with differential pricing according to daily peak and off-peak times.

When we first modelled EV payback periods, we assumed the cost of charging would be equivalent to the average residential power price of 16 pence per kilowatt hour (kWh). One of us (Gerard Wynn) has since bought an electric vehicle and signed up for the Octopus Agile tariff, which allows for setting a maximum charging price and automatically shifting charging to off-peak periods. In the past 30 days, for example, the average charge price has been five pence per kWh, with charge prices below one pence also being achieved.

What difference can time-of-use tariffs make to EV payback periods?

First, EV markets are changing so fast that the car Gerard is driving now was unavailable last year—a Renault Zoe ZE50 with a 52 kWh battery and 245-mile (394 km) range.

If we assume this car had been available last year and all other data were unchanged, the payback period would be approximately eight years. That isn’t good enough for most consumers. According to the Royal Automobile Club, the average car ownership period in the U.K. is just four years.

That disappointing payback period is partly because of a high price premium compared with the nearest equivalent, a conventional Renault Clio. We calculated the premium to be £7,000, based on a £26,000 purchase price for the new Zoe, versus £19,000 for the Renault Clio.

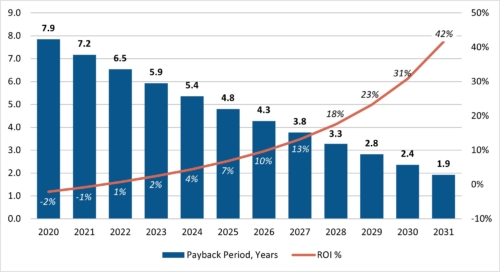

Fast-forward to this year. If we consider lower inflation and gasoline prices, and the lower EV grant, the payback period widens to 10 years. However, once we account for off-peak charging at 5 pence per kWh instead of 16 pence, this falls to fewer than eight years.

Switching to time-of-use-tariffs has cut EV payback periods by more than one-fifth

So, something as simple as switching to available time-of-use-tariffs has cut EV payback periods by more than one-fifth. But payback periods are still too long, at eight years—longer than the period we might expect to own the car.

The U.K. confirmed this week that it would ban the sale of new gasoline cars by 2030. By then, our modelling assumptions indicate the Renault Zoe payback period will be about two years. That’s much better.

That finding is based on our modelling assumptions: Falling EV battery costs (by 10% annually); a falling EV price premium (by £250 annually); rising EV driving efficiency (by 5% annually, versus 2% for a conventional vehicle); and continuing reductions in the EV purchase grant by 10% annually.

For now, it appears that EVs are still too expensive for mass adoption. According to our model, the U.K. government would have to more than double the EV grant to £7,000 from £3,000 to get payback periods shorter than four years.

That level of subsidy may be impossible in an era of cash-strapped, post-COVID recovery. At the least, however, our calculations show that the U.K. government should not reduce the EV grant by too much, too quickly, if it wants to lay a path that rewards early movers today, towards mass adoption of zero-combustion cars within a decade.

Chart: U.K. EV payback period and return on investment (ROI), assuming 5 pence per kWh charging price

Gerard Wynn ([email protected]) is an energy finance consultant.

Arjun Flora ([email protected]) is an IEEFA energy finance analyst.

Related articles

IEEFA report: Electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries can drive growth in rooftop solar

IEEFA update: Five reasons why now is a good time for a fee on carbon emissions