IEEFA: India's renewable energy journey: Two steps forward, one step back

Key Findings

Rooftop and decentralised solar power deserve special attention in India's push to expand solar capacity

Renewable energy now forms a quarter of India’s total installed power capacity – 110 gigawatts (GW) as of March 2022 – and accounts for 13% of the country’s electricity generation.

Under the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, India set ambitious targets to produce 50% of its electricity from renewable sources and install 450GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030.

A total of 65.6GW of solar and wind capacity has been added to the grid since the beginning of the fiscal year (FY) 2015/16.

More than 90% of India’s 54GW of solar capacity has been installed since FY2015/16. In the fiscal year that ended in March 2022, India added a record 13.9GW of solar capacity to the grid.

India’s ultra-mega solar park model has been tremendously successful in de-risking solar projects and upscaling solar capacity deployments. Reverse auctions in which the lowest tariff bidders are awarded contracts have been a game changer in making tariffs highly competitive. India’s solar parks are some of the largest in the world and offer tariffs below Rs2.5/kWh (~US$35/MWh) – nearly 50% lower than coal-fired power tariffs.

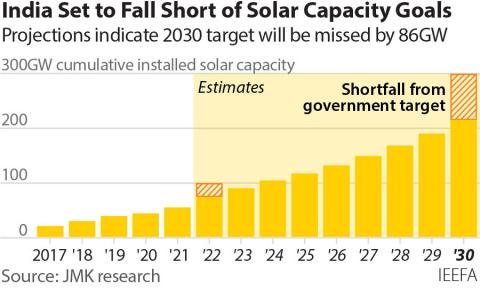

Despite these achievements, the capacity growth in solar still falls far short of the average annual build rate of 30GW that is required to achieve the target of 300GW of solar capacity by 2030. In the past few years, policy uncertainty around import duties and taxes, among other reasons, have slowed down growth in solar capacity.

The wind power sector has faced even bigger policy headwinds. Following a record year in FY2016/17 with 5.5GW of wind capacity additions, progress slowed to an annual average of 1.6GW over the last five years.

To replicate the success of reverse auctions in wind power development feed-in-tariffs were abolished in 2017. The competition rapidly brought down tariffs by 40%. However, margins shrank to unsustainable levels, with pressure to reduce costs and upgrade turbine technologies severely stretching the balance sheets of Indian wind turbine manufacturers.

To make matters worse, Solar Energy Corporation of India’s (SECI) ‘location agnostic’ wind power auctions have resulted in a concentration of project developments in a few states with the best wind resources such as Tamil Nadu and Gujarat. This has put pressure on land and networks in those states and caused delays in project commissioning.

Unleashing growth in solar

India could fully exploit its solar resources without putting undue stress on land and network infrastructure by giving special attention to distributed rooftop and decentralised solar power.

IEEFA recommended some short term and long-term policy moves that could provide a strong push for rooftop solar in India. Uniformity and consistency in net metering and banking regulation across all states is the most important change required to make rooftop solar viable for owners.

With stricter enforcement of the renewable purchase obligations (RPOs) for states, the state-owned distribution companies (Discoms) would allow more rooftop solar, because it can be built quickly and without putting significant pressure on the grid network.

Discoms' poor financial health is a major contributing factor to sluggish growth in rooftop solar. Privatisation of Discoms is potentially a long-term solution that would incentivise rooftop solar as it offers least-cost power to the grid.

Many Indian renewable energy developers have successfully raised debt capital through green bonds at competitive rates in the international market. These companies have also managed to tap significant international institutional capital.

At the same time, many top global utilities such as Enel, EDF and Statkraft are steadily establishing themselves with a strategy to be in the Indian market for the long haul.

In IEEFA’s view, there is enough global capital available to be deployed in the Indian market, but policy certainty and regulation is needed to strengthen investor confidence. India has installed record renewables capacity in the last fiscal year and rising electricity demand after COVID could become a springboard for the energy transition.

This commentary first appeared in The Economic Times.