IEEFA Europe: Legal Challenge to Spain’s Capacity Market Payments Is Well-Founded

A recent call by two environmental organizations for a formal state aid probe into Spain’s payments subsidizing gas- and coal-fired power plants appears to be well warranted, given multiple breaches of European state aid guidelines revealed by IEEFA in our December 2016 report, “Spain’s Capacity Market: Energy Security or Subsidy?”

A recent call by two environmental organizations for a formal state aid probe into Spain’s payments subsidizing gas- and coal-fired power plants appears to be well warranted, given multiple breaches of European state aid guidelines revealed by IEEFA in our December 2016 report, “Spain’s Capacity Market: Energy Security or Subsidy?”

The Instituto Internacional de Derecho y Medio Ambiente: IIDMA and La Plataforma por un Nuevo Modelo Energético (Px1NME), with the help of Client Earth, lodged the complaint two weeks ago, saying that the payments to power plants are made apparently without reason.

Capacity markets are meant to safeguard against power shortages – for example to back up wind and solar power when these are unavailable — by paying the operators of fossil fuel and other large power plants to keep the plants online, regardless of whether they generate electricity.

Spain’s capacity market is of interest because it was one of the first, introduced in 1997. And fossil fuel utilities, like those in Germany, are suddenly keen to promote capacity markets as a new, additional source of revenue as they struggle to compete with the growth of renewable power.

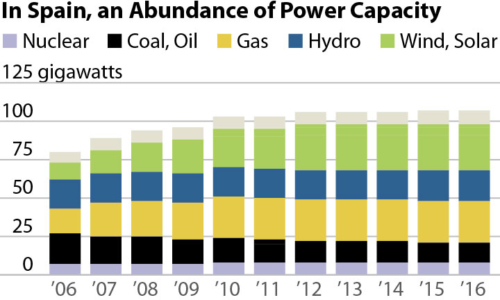

IEEFA agrees with the Spanish organizations’ assessment. If the goal of a capacity market is to safeguard against shortages, then Spain doesn’t need one. When the scheme was introduced in 1997, concerns about meeting rapidly rising demand were justified. But those days are long gone. Spanish power demand has stagnated since 2008.

Over-capacity in Spain is well-documented:

- The Spanish transmission service organization, Red Eléctrica de España (REE), calculates a safety margin where aggregated de-rated capacity should exceed peak demand by 10 percent. That margin was achieved in 2008, and has since risen to more than 40 percent..

- Combined cycle gas turbines (CCGT) in Spain have an average capacity factor of less than 10 percent, meaning they achieve less than a tenth of their maximum possible electrical output, because of low running times.

- In 2015, some 5 gigawatts (GW) of CCGTs produced no power at all. This capacity could be shut down without impacting grid stability; instead, operators receive capacity payments to keep them online, in the name of preserving security of supply.

- Some 80 percent of CCGT power plants are unable to recover their fixed cost on wholesale power markets without capacity payments.

The implication is clear: before deciding whether to continue capacity payments, Spain should first retire excess capacity, starting with the oldest, dirtiest power plants. That would save citizens money, given that they underwrite capacity payments worth nearly €1 billion annually in 2015. By shutting excess capacity, Spain would restore a more effective market price signal, which would incentivise flexible power plants more efficiently than handing them capacity payments for doing nothing at all. The price signal could be further restored by removing or reducing a price cap in day-ahead markets.

IEEFA found further ways in which Spain’s capacity market falls short of a good deal for consumers. First, the scheme excludes foreign capacity, and so hikes prices by isolating the Spanish grid. Second, capacity prices are set administratively, rather than by auction, further hiking costs. Third, payments for demand-side response (DSR) – where large consumers are paid to reduce electricity demand at times of system stress – is skewed to favour energy-intensive industries. And fourth, there is little transparency regarding the value for money for DSR payments, including how often industries are actually called upon to reduce demand.

In short, the scheme appears to favor powerful incumbent utilities and industries. That is probably because of a politicization of the electricity system, aided by the lack of an independent energy regulator.

The complaint filed by the two Spanish non-government organizations relates to the European Commission’s “State aid Sector Inquiry” into capacity mechanisms published last November. IEEFA found that Spain’s capacity market flouted almost all the commission’s guidelines, which include the removal of market price caps, the inclusion of interconnection and overseas capacity, and a preference for auctions over administered prices.

Capacity markets in general don’t work. Generic problems include: erosion of price signals through out-of-market payments; a risk of political intervention; a tendency towards over-capacity; and the creation of a sclerotic electricity system, by picking winners years ahead of delivery, at a time of massive technology disruption, not least from decentralised solar, digitalised grids, and electric vehicles.

Spain was an early mover when it introduced its capacity market. It is now time to move again, towards a fairer, less costly and more transparent system for securing low-carbon electricity.

Gerard Wynn is an IEEFA energy finance consultant.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Update: A Rush to Subsidies as Power Plants in Europe Face an Existential Threat

IEEFA Europe: Can Coal Power Hang On?

IEEFA Europe: ‘Capacity Payments’ Provide a Lifeline to Costly Coal-Fired Generators