Electric Grid Managers: Quasi-Public Corporations Gone Wild (and in Secret)

A fact little known to most Americans is that the grid they rely on for electricity is controlled by quasi-public organizations whose lavishly paid executives and board members conduct business in deep secret.

Independent system operators, or ISOs, work almost entirely behind closed doors, even though their every action affects public electricity customers of all stripes—residential, business and public sector.

I call them quasi-public because so much of what they do so profoundly affects the utility-consuming public, even as their corporate structure and inner workings are shrouded in mystery. ISOs in effect are public agencies exempt from public scrutiny—and, as a sadly predictable result, quasi-public corporations gone wild.

A little background: ISOs run the electric grid region by region across the United States. Some cross state lines. Those include PJM (whose initials are derived from its footprint: Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Maryland) and MISO (Midcontinent Independent System Operator: 11 Midwestern states and part of Canada). Others, such as NYISO, the New York Independent System Operator, are confined to one state.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) mandates that each ISO ensures that enough electricity is generated across the grid to avoid blackouts. FERC also charges each ISO with making sure electricity is fed into the grid at competitive prices and that the appropriate power-generation mix is in place.

Who knows, though, if any of this is happening?

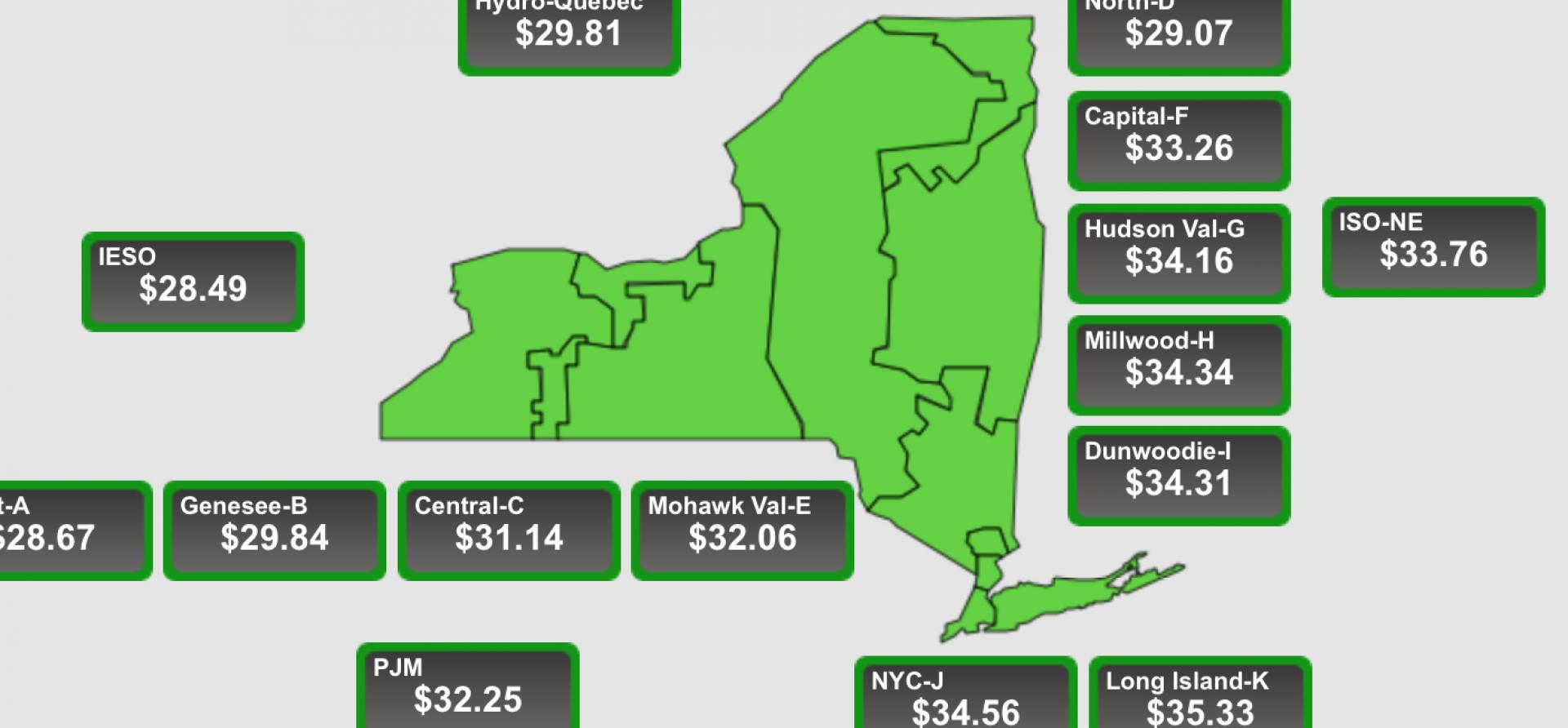

NYISO is a good case study. While it conducts so-called auctions to determine how much electricity will cost, these events are managed according to extremely arcane rules that seem designed to obfuscate rather than illuminate. In its murky dealings, NYISO also provides a system of ratepayer subsidies to prop up aging power plants that may rarely operate but are deemed necessary in case demand exceeds supply. These plants, sometime referred to as “reliability-must-run” facilities, are often nuclear or coal-fired, which means they don’t fit into the new energy economy that is taking root, but that their owners are subsidized for keeping dinosaurs alive.

These practices by NYISO raise a multitude of questions that go unanswered because NIYSO operates so far beyond public view. Are NIYSO auctions conducted in a manner that is truly in the public interest? Are the subsidies it hands out to old plants truly in the interest of NIYSO’s millions of customers? Does the organization follow policies that benefit public health and the environment?

NYISO’s tax filings—which by law are public because the organization positions itself as a tax-exempt nonprofit—hint at just how well the people who control ISOs are compensated. According to the NYISO’s 2013 tax return, Stephen G. Whitley, its president and CEO, was paid $1,804,749 that year. I’m not saying Whitley didn’t deserve that much. His is specialized work and his average workweek was said to be 60 hours. It’s still a lot of money. The members of the NYISO’s part-time board of directors also did okay. For working a reported 12 to 16 hours per week, they took home from $55,167 to $156,500 in 2013. Nice work if you can get it.

NYISO’s tax filings—which by law are public because the organization positions itself as a tax-exempt nonprofit—hint at just how well the people who control ISOs are compensated. According to the NYISO’s 2013 tax return, Stephen G. Whitley, its president and CEO, was paid $1,804,749 that year. I’m not saying Whitley didn’t deserve that much. His is specialized work and his average workweek was said to be 60 hours. It’s still a lot of money. The members of the NYISO’s part-time board of directors also did okay. For working a reported 12 to 16 hours per week, they took home from $55,167 to $156,500 in 2013. Nice work if you can get it.

Add to these very good personal payouts the fact that board members choose their board cronies—without public review—whenever there’s an opening, and you have a system that ensures perpetuation.

Here are a few examples of how NIYSO stacks up against most state agencies with such far-reaching public impact:

- Government agencies are covered by New York’s open-meetings law. Important decisions have to be made in public. Reporters and other members of the public are allowed to attend meetings. Not true for NYISO.

- Government agencies are covered by New York’s Freedom of Information Law. Important documents are typically available for review by reporters and other members of the public. Not true for NYISO.

- Government agencies are covered by the State Administrative Procedure Act. A standard system allows for input from the public that must be followed before any significant decision is made. Not true for NYISO.

- Government agencies are covered by the State Environmental Quality Review Act. Any action by the agency that may have a significant environmental impact must first be subject to an environmental impact statement. Before such a statement can be finalized, members of the pubic must be given an opportunity to comment. Not true for NYISO.

Can NYISO’s dark practices change?

I think so, and perhaps sooner than later. Indeed, a public discussion is likely to occur in New York over the next year or so on how to reform NYISO and bring it into the light of the 21st century. And that’s good news, because NYISO is doing the public’s business, and the public has a right to know about it.

Larry Shapiro is IEEFA’s board president and associate director for program development at the Rockefeller Family Fund.