Delayed U.S. coal plant closures are bumps in the road, not U-turns for energy transition

Transition continues to gain momentum even with COVID-19 and Russia headwinds

Technology transitions can be messy things that don’t always progress in a perfectly linear fashion. But once started, they are virtually impossible to stop. In the energy transition underway in the U.S., recent decisions by electric utilities to delay planned closures of several coal plants underscore the relevance of both sentences.

For example, two major utilities in Wisconsin, WEC Energy Group and Alliant Energy, announced last month that they were pushing back closure plans at several coal plants due to concerns about tight energy supplies in the Midwest and delays in completing new wind and solar project due to pandemic-induced supply chain issues.

These delays are just that, not a fallback to fossil fuels

Alliant said it would delay closing the last still-operating unit at its Edgewater coal plant by six months, until June 2025, and push back the closure of the two-unit, 1,150 megawatt (MW) Columbia Energy Center by 18 months, until June 2026. Similarly, WEC’s operating subsidiary, Wisconsin Electric Power, said it was pushing back the closure of its four-unit, 1,112MW South Oak Creek coal station by 12 to 18 months, delaying the retirement of two units by 12 months and the other two by 18 months.

Similar problems have surfaced recently in Missouri, Nebraska and New Mexico, with utilities slowing transition plans away from coal largely due to construction delays with planned replacement wind and solar generation amid tight power supplies. Global supply chain problems have contributed to construction problems for both resources. In addition, the federal government’s investigation into potentially unfair trade practices by China delayed many solar projects earlier this year because of the threat of retroactive tariffs on projects using Chinese material. The investigation is still ongoing, but the administration has eliminated the threat of post-fact tariffs, bringing the U.S. market back to life.

But these delays are just that, not a fallback to fossil fuels.

Alliant, for example, just received regulatory approval for the second phase of a 1,100MW solar buildout. Construction is scheduled to begin this summer, with commercial operation slated for late 2023. In normal times, that would not be an overly aggressive construction schedule—but these are not normal times.

“It’s important to recognize the unprecedented and unexpected circumstances currently affecting the entire energy industry,’’ said David de Leon, president of Alliant’s Wisconsin Power and Light subsidiary. “Shifting the retirement dates for our coal-fired facilities in Wisconsin helps ensure we can weather multiple uncertainties while continuing to add cleaner, renewable energy to the grid.”

Ameren is another telling example of the messiness of the coal to clean transition. The company, which has utility operations in both Illinois and Missouri, fought for years to keep the two-unit, 1,244MW Rush Island coal plant open despite a lengthy court fight over improper upgrades to the facility. The Environmental Protection Agency filed suit in 2011, arguing that the upgrades violated the Clean Air Act and required the company to install pollution control equipment to cut its sulfur dioxide emissions. The utility disagreed. The case worked its way through the system for years, culminating with an appeals court ruling in 2021 affirming EPA’s contention and requiring air pollution upgrades at the plant. Until that ruling, the company was planning to keep Rush Island online until 2039; just months after the ruling, however, it announced plans to close the plant in 2024.

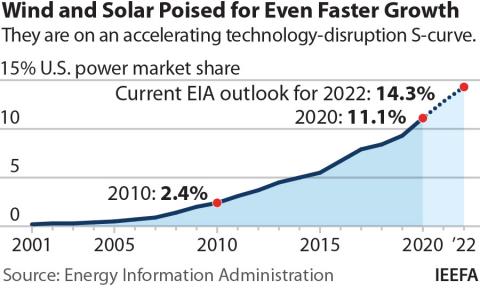

There now is some uncertainty as to whether the plant will close in 2024 or 2025, with the completion of needed transmission upgrades likely driving the final decision. But its closure is coming years earlier than previously planned, and that largely can be attributed to the commercial rise of cost-competitive clean alternatives. In 2011, when the suit was filed, there were 40,100MW of wind capacity installed in the U.S. and just 1,052MW of utility-scale solar. By the end of 2021, installed wind and utility scale solar capacity had risen to 132,401MW and 61,014MW, respectively. Both are still growing rapidly despite the current supply chain problems.

The enormous growth of renewables is also clearly evident in the latest national generation data

At Ameren, the change is clearly apparent in the utility’s long-term integrated resource plans (IRPs). In its 2017 IRP, the company said it expected to add 100MW of solar capacity in the coming 10 years—a meager 10MW annually. In its 2020 IRP, Ameren projected that it would add 2,700MW of solar in the coming 20 years. Although not overly aggressive, the change to 135MW annually represents a clear expansion of the utility’s transition efforts. This transition is similarly evident in Ameren’s approach to its coal-fired generation. In 2017, it touted plans to retire half of its coal generation in the coming 20 years. Just three years later, the utility was planning to retire all of its coal by 2042. Again, the retirements are a clear sign that the transition’s momentum is undiminished.

At PNM, the New Mexico utility revised plans to close its San Juan coal-fired generating station after pandemic-induced delays slowed the completion of new solar projects being built to replace the 847MW of capacity at the plant. The utility is extending the closure of its final operating unit, the 507MW Unit 4, by a few months to keep it available through the summer peak demand period but will still shutter it this fall. Already moving forward with significant new renewable generation projects, the utility issued a new request for proposals in May for 700MW of generation to be online no later than May 2024.

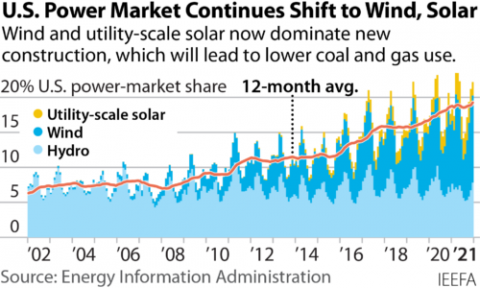

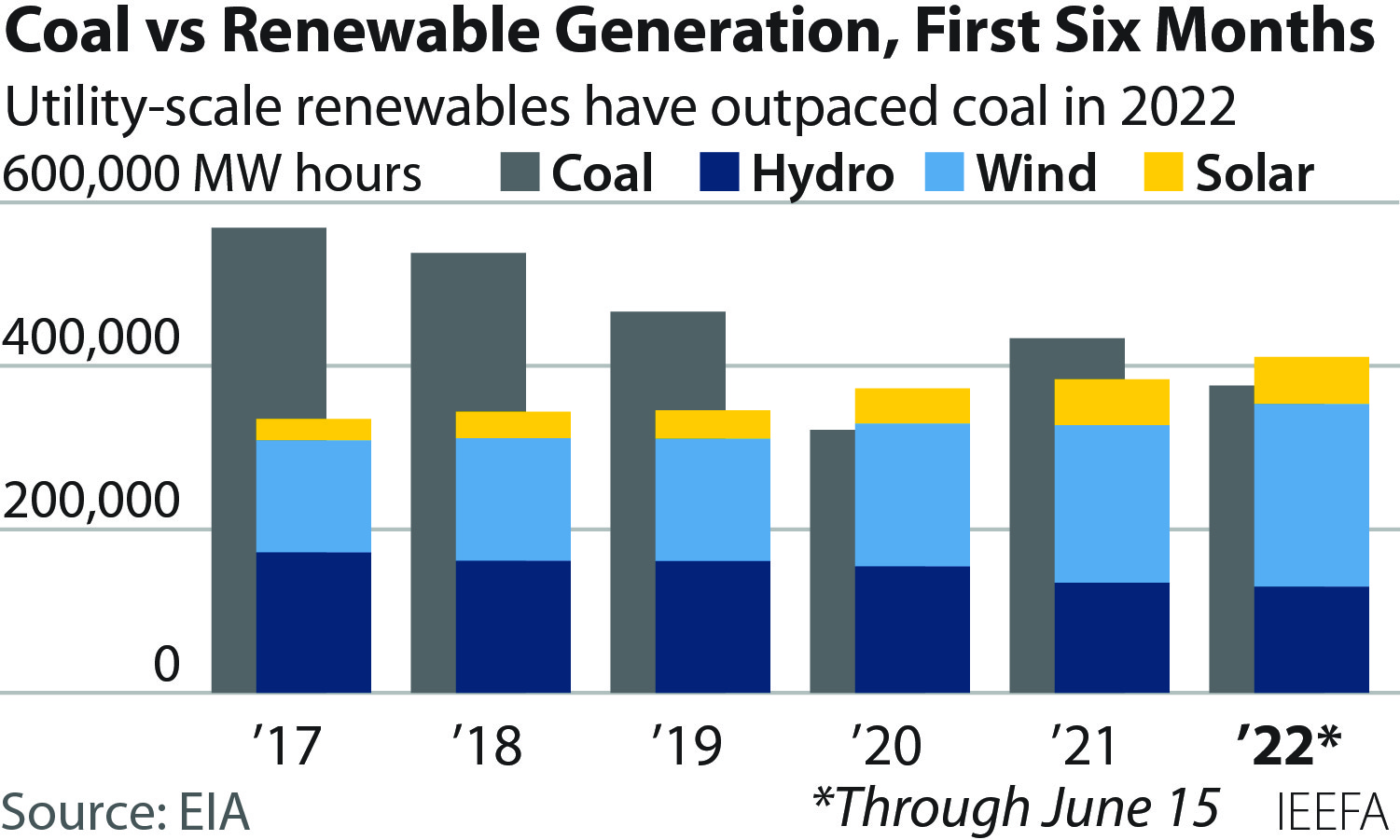

The enormous growth of renewables is also clearly evident in the latest national generation data. Through June 15, generation from wind, solar and hydro totaled 411.1 million megawatt-hours (MWh), up 30.4% since 2019. To date this year, renewables have accounted for 23% of total electricity demand, second only to gas-fired generation. In 2019, renewables were the fourth-largest generation resource, behind gas, coal and nuclear. (The data cited here run through June 15 of each year because data problems at the Energy Information Administration have prevented them from updating its hourly generation website.)

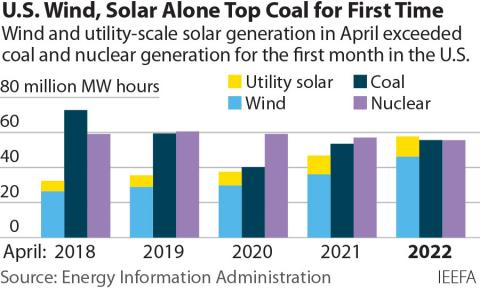

The strong growth led to a milestone in April, when combined utility-scale solar and wind (without adding hydro) produced more electricity than either coal or nuclear, vaulting these green resources into the second spot in U.S. power production. IEEFA expects solar and wind will top coal and nuclear in more individual months, before soon topping both on an annual basis. Already, for example, EIA projects that wind and solar generation will top coal in March, April and May of 2023.

This wind and solar-led transition is likely to follow the same trajectory as the earlier shift including hydro in the renewables mix. IEEFA noted in April 2019 that utility-scale solar, wind and hydro had topped coal generation in a month for the first time; EIA now projects that wind, solar and hydro will generate more electricity than either coal or nuclear over the entire year in 2022.

The renewable gains since 2019 are all the more notable given that hydro generation has continued to struggle, dropping 20.7 million MWh during this span. In other words, increases in wind and solar generation are not only eating into coal and nuclear’s market share, but also covering for the decline in hydro output.

In 2019, hydro was still the leading renewable electricity resource, but wind has surged ahead as the largest source of green electricity, and now accounts for more than 12% of total U.S. electricity output by itself. Starting from a smaller base, solar has grown even faster than wind since 2019, with output more than doubling to 57.7 million MWh from 27.6 million MWh.

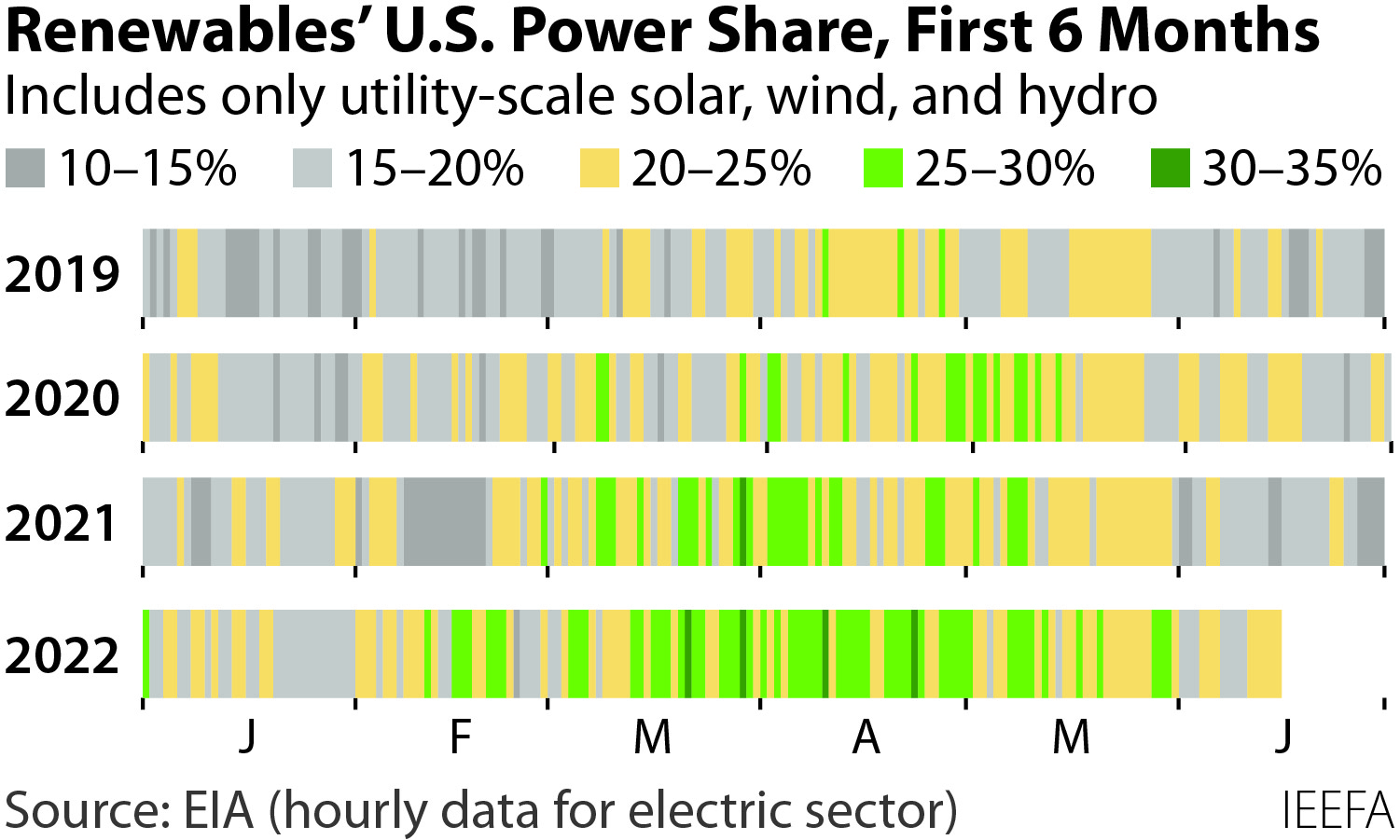

Another way of looking at the rapid, but messy transition now underway is in the following graphic. Through June 15, renewables accounted for 25% or more of daily U.S. generation on just three days. So far in 2022, renewables have topped 25% on 59 days.

Another interesting data point from EIA’s hourly grid monitor: In 2021, total daily solar generation never topped 400,000MWh; through June 15, 2022, solar had topped that mark on 61 days or almost 37% of the time.

A rapid transition is underway. Current events represent bumps in the road, not a change in direction.